שיתוף הפעולה של ישראל עם קפריסין ויוון להקמת צינור תת-ימי להובלת גז טבעי מאתגר את תכניותיה של טורקיה להפוך לשחקן אנרגיה מרכזי באזור הים התיכון ומהווה פוטנציאל לחיכוך בים בין שתי המדינות, שעלול להסלים.

הערכת המודיעין השנתית של צה”ל שהתפרסמה ב-15 בינואר [2020] כוללת לראשונה את המדיניות האזורית האגרסיבית של הנשיא רג’פ טאיפ ארדואן ברשימת האתגרים הניצבים בפני ישראל, אם כי אינה רואה באופק עימות ישיר עם טורקיה. אבל התבוננות בקשרים הצוננים בין ישראל לטורקיה חושפת כי ההסלמה באה לידי ביטוי לא רק בתחום הפוליטי-פלסטיני או במלחמה בטרור, אלא גם בתחום האנרגיה.

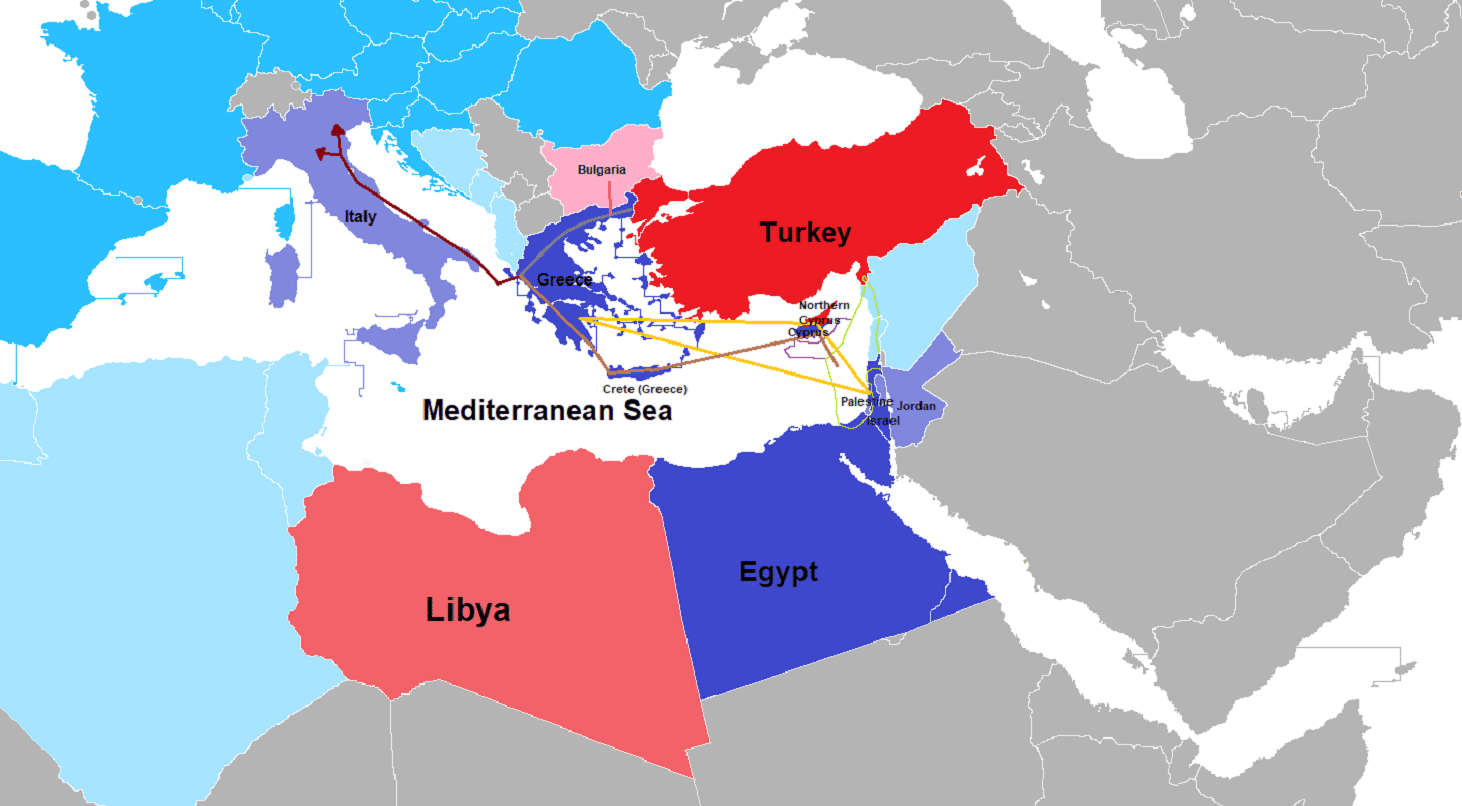

ב-2 בינואר, ישראל, יוון וקפריסין חתמו על הסכם להקמת צינור תת-ימי להובלת גז טבעי ממצבורי הגז במזרח הים התיכון לאירופה. פרויקט הצינור אמור לשנע גז טבעי משדות הגז של ישראל וקפריסין – תחילה לאיטליה ומשם לשאר אירופה, ולהבטיח ליבשת אספקה סדירה של גז שמקורו אינו ברוסיה. אולם לצד ההישג הדיפלומטי, הפרויקט מסלים את המשבר בין שלוש המדינות הללו לבין טורקיה בתחום האנרגיה ובאופן כללי.

חתימת ההסכם היא צעד נוסף בעשור של שיתוף פעולה גובר בקרב שלוש המדינות בעקבות תגליות הגז במים הטריטוריאליים של ישראל. שיתוף הפעולה האנרגטי תפש תאוצה לפני שנה [2019] עם הקמתו של פורום הגז של מזרח הים התיכון. פורום ייחודי זה, שמטרתו לקדם שיתוף פעולה אזורי בתחום האנרגיה, כולל את שלוש המדינות וכן את מצרים, ירדן, הרשות הפלסטינית ואיטליה. צרפת ביקשה להצטרף ואילו ארה”ב מבקשת לשמש משקיפה קבועה.

ראש הממשלה בנימין נתניהו ציין במעמד החתימה כי “זהו יום היסטורי לישראל, משום שישראל הופכת במהירות למעצמה אנרגטית, למדינה שמייצאת אנרגיה…זהו גם יום היסטורי, משום שיש כאן שיתוף פעולה שהולך ומתבסס בין יוון, קפריסין וישראל. ממש ברית במזרח הים התיכון, שהיא גם כלכלית, היא גם מדינית והיא גם מוסיפה לביטחון וליציבות של האזור”.

חרף התלהבותו של נתניהו, הסכם הגז הנוכחי אינו כצעקתו. הכדאיות הכלכלית שלו אינה ברורה נוכח עודפי הגז הקיימים ומחירו הנמוך של הגז. גם האתגרים הטכנולוגיים ואבטחתו של הצינור התת-ימי הארוך בעולם מעוררים חששות כבדים. ישנם מומחים שטוענים כי הנזלת גז במתקנים הקיימים במצרים ובאלה שנמצאים בתכנון, עשויה להיות חלופה עדיפה.

עם זאת, עוד בטרם החלה החפירה התת-ימית, ישראל כבר נהנית מהפירות הדיפלומטיים של הפרויקט. שיתוף הפעולה בין שלוש המדינות כולל מסגרת מדינית, לרבות מפגשי פסגה קבועים של שרים ומנהיגים. המדינות השותפות גם הגבירו את שיתוף הפעולה הביטחוני והצבאי ביניהן, במיוחד באמצעות תרגילים משותפים. בעקיפין, המפתח לברית המתפתחת הוא האגרסיביות הגוברת של טורקיה בסוגיות אזוריות, כמו גם המצב העגום של יחסי ישראל-טורקיה מאז עלייתו לשלטון של הנשיא ארדואן, ובמיוחד מאז תקרית משט המרמרה ב-2010. מבחינתן של יוון וקפריסין, שיתוף הפעולה הגלוי עם ישראל תורם להרתעה שלהן מול טורקיה.

אכן, טורקיה הגיבה באופן שלילי להסכם הצינור. היא רואה בפורום הגז כלי נוסף לצמצום צעדיה הגיאופוליטיים במזרח הים התיכון והדרתה מאוצרות הגז באזור. בנוסף לכך, הפרויקט מאיים על האסטרטגיה הטורקית להפוך למרכז של הולכת אנרגיה בין מזרח למערב (צינור הגז TurkStream מרוסיה לבולגריה נחנך ב-8 בינואר על ידי הנשיאים ולדימיר פוטין וארדואן). נראה גם כי קיים רצון אמיתי מצד ממשלת טורקיה לקבע את ההגמוניה שלה בסביבתה הקרובה ולהשיב לעצמה את מעמדה מהתקופה העות’מנית כמעצמה ימית לאורך חופי הים התיכון. הדבר בא לידי ביטוי בתכניותיה להתעצמות ימית, הכוללות תוספת של יותר מ-20 ספינות בשלוש השנים הקרובות.

מעבר למוטיבציות צבאיות ודיפלומטיות, מדיניותה של טורקיה בתחום הכוח הימי והאנרגיה משרתת מטרות פנימיות. עימות עם כוחות שאינם מוסלמים, במיוחד קפריסין, הוא מהלך פופולרי בקרב בסיס תומכיו של ארדואן במפלגת הצדק והפיתוח, כמו גם בקרב שותפיו הלאומנים (הלא-מוסלמים) בקואליציה.

טורקיה לפיכך הודפת ניסיונות ל”הקפתה” על ידי הארכיטקטורה האסטרטגית במזרח הים התיכון שאותה ישראל (ומצרים) מנסה לפתח. היא שיגרה ספינות קידוח בליווי של חיל הים לבצע חיפושי גז במים שאותם תובעת קפריסין כמו גם הרפובליקה הטורקית של צפון קפריסין. כוחות ימיים טורקיים איימו על ספינות מחקר קפריסאיות באזורים השנויים במחלוקת, ובנובמבר 2019 סילקו ספינת מחקר ישראלית מהאזור.

הודעתה של אנקרה מה-27 בנובמבר [2019] על הסכם שחתמה עם הממשלה הלובית הזוכה להכרה בינלאומית בהנהגתו של פיאז א-סאראז’, שתוחם גבולות ימיים בין שתי המדינות ומבתר את הים התיכון (תוך התעלמות מאיי יוון), מוסיפה אף היא למתיחות. מבחינת טורקיה, מטרתו הברורה של ההסכם עם לוב הייתה לעקוף את פורום הגז האזורי ולחסום את המסלול העתידי של צינור הגז לאיטליה ומערב אירופה, ובכך לנפץ את תקוותיה של קפריסין, להרתיע משקיעים פוטנציאליים ולחייב את הצדדים לשתף את אנקרה.

נדמה כי תזמון החתימה על הסכם הצינור במזרח הים התיכון נועד לאתגר את מהלכיה של טורקיה. הסכם הגבולות הימיים עובה בכוונות מוצהרות של טורקיה לסייע לסאראז’ באמצעות חיילים. מאמצים משותפים שנעשו בעת האחרונה על ידי פוטין, שתומך בממשלה לובית יריבה בהנהגת חאליפה חפתר, ושל ארדואן, להשיג הפסקת אש בלוב, מצביעים על הצלחתו של ההימור הטורקי.

האם ייתכן שהיריבות הישראלית-טורקית תצא מכלל שליטה? ישראל רואה בטורקיה תחת ארדואן יריבה, אם כי משנית לאויביה המיידיים והאלימים יותר. המתיחות הנוכחית מתפתחת על רקע תחילת הזרמתו של גז טבעי משדה לויתן לירדן ומצרים ב-15 בינואר.

ראש הממשלה נתניהו הגדיר את ייצור הנפט, ובמיוחד את ייצואו, כחיוני לביטחון הכלכלי ארוך הטווח של ישראל. שיתוף הפעולה בתחום הגז במזרח הים התיכון והברית המשולשת הם מרכיבי מפתח בחזון ארוך הטווח שלו עבור ישראל כמעצמה על-אזורית, כמו גם בנרטיב הבחירות שלו כהוכחה לראייתו החדה בתחום האסטרטגי והצלחתו. בניסיונותיה לאיין את ההישג הזה, טורקיה עלולה להפוך לאיום ברמה גבוהה יותר.

לפי הדיווחים, טורקיה הציעה באחרונה לדון עם ישראל בסוגיית הגז. ישראל אינה מעוניינת בעוינות גלויה עם טורקיה והיא מקפידה להמעיט בחשיבותם של ההיבטים האנטי-טורקיים בברית האזורית שהיא מעצבת. מתיחות גוברת עלולה לאיים, למשל, על הסחר הימי החיוני של ישראל. גם עימות בין ישראל לבין חברה בנאט”ו הוא תסריט בלהות. מה שעוד מכתיב את עמדתה המדודה והבלתי מתלהמת של ישראל היא הבנתה כי קפריסין ויוון אינן מסוגלות ואינן נוטות לנקוט מהלכי נגד צבאיים משמעותיים בכוחות עצמן.

עם זאת, אין זה בלתי סביר כי בקרוב יפרסו ישראל וטורקיה את חילות הים שלהן במטרה להקרין את כוחן הלאומי ולהגן על נכסיהן הקיימים והפוטנציאליים. כפי שכבר הוזכר, מקרה אחד (שלא היה אלים) התרחש בנובמבר 2019 בין ספינות ישראליות לטורקיות. טורקיה גם שלחה ספינות מלחמה לביקור בצפון אפריקה, ואף דווח כי פרסה כלי טיס בלתי מאוישים בקפריסין הטורקית.

חשיבות הגז וסוגיות התעבורה הימית לשתי המדינות, מחסור במנגנונים מספקים לניהול משברים ביניהן בשל היחסים המוקפאים בתחום הדיפלומטי והבין-צבאי, והצורך של שני המנהיגים להציג עצמם כנחושים ובלתי מתפשרים, מהווים פוטנציאל לחיכוך בים, שעלול להסלים. הפוטנציאל לאלימות בין הצדדים גבר, ואף כי אינו גבוה הוא כבר אינו זניח.

פורסם ב-אל-מוניטור 23.01.2020

סדרת הפרסומים “ניירות עמדה” מטעם המכון מתפרסמת הודות לנדיבותה של משפחת גרג רוסהנדלר.

תמונה: (Adam Hegazy337259 [CC BY-SA 4.0)] (cropped

- בניית אתרים

- בניית אתרים