האזהרות הנשמעות באחרונה בארה”ב לגבי מדיניותה של ישראל כלפי סין ראויות לתשומת לב, ויש סוגיות שבהן אכן נדרשת זהירות יתרה. יחד עם זאת, האסטרטגיה של ישראל בזירה האסיינית אינה מתנגשת עם האינטרסים של ארה”ב; אדרבא, היא משרתת ומחזקת אותם. שותפות עם בייג’ינג במימד הכלכלי והתשתיתי עשויה לסייע בייצובו של המזרח התיכון. במקביל, שותפות בתחומי הביטחון עם כמה ממדינות אסיה עשויה לסייע ביצירת משקל נגד לחששות שמעורר כוחה העולה של סין.

בשבועות האחרונים מתנהל דיון רציני מעל דפי כתב העת המקוון ‘מוזאיק מגזין’ לגבי יחסי ישראל-סין. תחילה הופיע מחקר מפורט של ארתור הרמן, מלומד מכובד בנושא היבטי מדיניות החוץ של ישראל. אחריו באו אזהרות חמורות מפי אחד המומחים הגדולים של ארה”ב לענייני סין, דן בלומנטל, שטען כי “החיבוק של ישראל עם סין הוא שגוי ביותר”, ומפי ידיד טוב ועקבי, אליוט אברמס, שכתב ש”אסור לישראל להניח ליחסיה הכלכליים עם סין לאיים על יחסיה המדיניים עם ארה”ב.”

בתגובה לכך, מוצעת כאן נקודת ראייה שונה במקצת, ואולי מאוזנת יותר, על התפתחותם יחסיהן של ישראל-סין (זוהי גרסה מורחבת ומעודכנת של התגובה שפרסמתי בעיתון ‘מוזאיק’).

אל מול האזהרות – שיש להתייחס אליהן בכובד ראש, ויש בהן היבטים המחייבים מעקב קפדני של כלל גורמי המערכת, לבל ניקלע למהדורה נוספת של משברי ה-“פאלקון” וה-“הארפי” – ניתן להשיב, בזהירות הראויה, כי האסטרטגיה של ישראל ביחס לסין אינה מתנגשת עם האינטרסים של ארה”ב; אדרבא, היא משרתת ומחזקת אותם. שותפות עם בייג’ינג עשויה לסייע בייצובו של המזרח התיכון. שותפות ביטחונית עם מדינות אסיה הרואות עצמן מאוימות על ידי בייג’ינג עשויה לסייע ביצירת מאזון כוחות יציב, ומשקל נגד לכוחה העולה של סין.

בסוף אוקטובר 2018, ערך סגן נשיא הרפובליקה העממית של סין, וואנג צ’ישאן, ביקור יוצא דופן בישראל, שבו השתתף, ביחד עם רוה”מ נתניהו, במושב הרביעי של פסגת החדשנות של ישראל. כמוהו השתתף בכינוס גם ג’ק מא, המייסד והמנכ”ל של ‘עליבאבא’. זהו סימן נוסף לכך שאנשי עסקים מובילים ורציניים בסין לוקחים את ישראל ברצינות, למרות השוני הבולט בין שתי המדינות מבחינת ממדיהן וגודל אוכלוסייתן. הביקור, כמו גם דפוס שיתוף הפעולה שנוצר במושבים הקודמים של ועידת החדשנות המשותפת ישראל-סין (שנוהלו בידי סגנית ראש ממשלת סין, ליו יאנדונג, מתוקף תפקידה כיו”ר שותפה, ביחד עם נתניהו), מחזקים את תיאורו של ארתור הרמן לגבי היחסים ההולכים ומתהדקים בין שתי אומות עתיקות אלו, השונות כל-כך זו מזו, אך גם מכבדות אחת את רעותה.

למרות זאת, יש לבדוק אם אכן קיימת הצדקה לחששו של הרמן שישראל תיסחף אל כוח המשיכה של סין, ואולי אף תשמש כחור פעור בהגנה הטכנולוגית של המערב מפני חדירותיה ושאיפותיה של זו. “אַשְׁרֵי אָדָם מְפַחֵד תָּמִיד” (משלי כ”ח, י”ד)! ואכן, האזהרות החמורות שאליהן מתייחס הרמן, בעיקר התרעתו של שאול חורב לגבי עתידו של נמל חיפה, אינן חששות בטלים, גם אם עיון בפרטי הנוכחות הסינית בחיפה יש בו כדי להרגיע את חלקם.

על פי דו”ח שפורסם לאחרונה בעיתון ‘הארץ’ (9.11.18), פקידים אמריקניים לא הסתירו את כעסם לנוכח האפשרות שתאגידים סיניים יקבלו לידיהם את בנייתו של נמל חיפה החדש, המשמש כנמל ביקור לצי השישי של ארה”ב (בפועל, מדובר רק במקטע מרוחק של הנמל שינוהל על ידי הסינים). יתרה מכך, סין היא כיום מתמודדת חריפה בתחום הסייבר (שעליו הרמן אינו מרחיב). למציאת נקודות תורפה בהגנות הסייבר של ישראל עלולות להיות תוצאות חמורות ביותר. למרות זאת, התיאור שלו לגבי המצב – שמשקף אולי את עמדות ממשל טראמפ בנושא – מפריז בעוצמתם של איומים אלה. הוא גם אינו לוקח בחשבון את הקשת הרחבה יותר של אינטרסים ישראליים באסיה, שדווקא עולים בקנה אחד עם אלה של ארה”ב.

ראשית, מדיניותה המתהווה של בייג’ינג באזור היא אכן בעלת חשיבות רבה עבור ישראל. די אם נתאר את האינטרסים של ישראל מנקודת מבט כלכלית צרה: סין מהווה שוק כלכלי ומקור השקעות עבור כלכלתה הגדלה והולכת של ישראל. עבור מדינה שתלויה כיום לגמרי בסחר במוצרים מתקדמים ובעלי איכות גבוהה, אין זה דבר של מה בכך. לא פחות חשוב מכך הוא תפקידה הפוטנציאלי של סין כגורם אסטרטגי מייצב באזור. כפי שנותח בהרחבה במחקרי על מצרים, שפורסם לאחרונה ע”י JISS, מעטים הדברים שעלולים להזיק לסיכויי ההישרדות של ישראל באזורנו רווי המלחמות, כמו התמוטטותה של מצרים למצב של תוהו ובוהו וחוסר תפקוד (או גרוע מכך, תפיסת השלטון במצרים על ידי האסלאמיסטים). כניסתם של הסינים לאזור כמשקיעים אסטרטגיים לטווח ארוך, המסייעים לקיים את צמיחתה ואת יציבותה של מצרים, היא בהחלט לטובת האינטרסים של ישראל ושל ארה”ב כאחת: למשל, כניסתם כקבלני מפתח בהקמת הבירה “האדמיניסטרטיבית” החדשה של מצרים – שטרם ניתן לה שם! – הנבנית ממזרח לקהיר. זהו אינו משחק בסכום אפס; זהו מצב שבו לכל הצדדים יש מה להרוויח.

נכון, סין אכן שומרת על יחסים חמים עם איראן. אך כפי שמציין הרמן (כשהוא מצטט את סם צ’סטר), ישראל הצליחה בשעתו להסביר לסינים שאם לא יינקטו צעדים לריסון הפרויקט הגרעיני של איראן, יקלע האזור כולו לתוהו ובוהו, שיהיו לו השלכות הרסניות על היציבות הגלובלית ועל צמיחתה הכלכלית של סין: ליתר דיוק, בשנת 2010, כשמשלחת בראשותו של השר דאז לעניינים אסטרטגיים, משה יעלון, ובהשתתפותי, הגיעה לבייג’ינג, הצליחה ישראל למנף את האיום הצבאי האמין שלה לכדי הצבעת “כן” של הסינים לטובת החלטה 1929 של מועצת הביטחון של האו”ם, שכפתה סנקציות מרחיקות-לכת על איראן. גם כיום, חישוב מפוכח מצד סין, בשילוב מסע הסברה נמרץ מצד ישראל וארה”ב – אשר יש לקוות שיהיה לו משקל בפסגת טראמפ-ש’י המתוכננת – יכול עדיין לשכנע את בייג’ינג שתמיכה באיראן תהיה כרוכה במחיר כבד מדי מבחינתה. זוהי עוד סיבה טובה מדוע עלינו להמשיך ולשמור על ערוץ הידברות פתוח עם סין.

בכל אופן, תיאורו של הרמן לגבי האתגר שמהווה סין מתעלם – בפועל – מההיבט החשוב ביותר של מדיניות ישראל באסיה. עיקר המאמצים הביטחוניים של ישראל אינם מכוונים אל סין – שישראל, לאור לקחי העבר, נמנעת בקפידה מלמכור לה מרכיבים בעלי משמעות צבאית – אלא דווקא אל קשת המדינות שסביבה, השואפות לבנות יכולת אסטרטגית (ועוצמה צבאית) שתהווה משקל-נגד למאמציה החדשים של סין, המתפרשים כמכוונים לכינון הגמוניה באזור. יתכן שסין אכן מטפחת שאיפות מרחיקות לכת בכיוון זה. איוואן אוסנוס מדבר על כך בספרו המצוין על סין המודרנית, “עידן השאיפות” Evan Osnos, The Age of Ambition) ) – אלא ששאר המדינות בַקֶשֶת המשתרעת בין הודו ליפן לא ממש מוכנות לקבל עליהן את שליטתה של סין.

מבחינתן, מסתמנת ישראל כשותפה בכירה בבניית יכולות צבאיות משמעותיות, במסגרת המאמץ הכולל לשמור על מאזן הכוחות באזור. במהלך השנים האחרונות הסירה יפן את הסתייגותה המסורתית משיתוף פעולה ביטחוני; וייטנאם והפיליפינים התגלו כשווקים חשובים למוצרי התעשיות הביטחוניות של ישראל; ושיתוף הפעולה עם אוסטרליה התעצם. מעל לכול, יחסיה של ישראל עם הודו, במונחים של רכישת חומרה צבאית וידע המאפשר ייצור בהודו Make in India”” כסיסמתו של רה”מ נארנדרה מודי), הפכו לנרחבים ואינטימיים יותר מכפי שהיו אי-פעם, מאז כינונם בשנות ה-90 של המאה הקודמת.

כל זה מתרחש בעוד ישראל נמנעת במתכוון, בהתאם לתנאיו של הסכם מגביל ביותר בינה לבין ארה”ב, מלמכור לסין כל סוג של נשק, תחמושת או טכנולוגיה דו-שימושית. מכאן הגיונו של המאמץ האינטנסיבי לחבור אל הסינים בתחומים אחרים, החל ממים ושירותים רפואיים וכלה במיזמי בניה סיניים בישראל. הוא אינו צריך להתפרש כמסמן מסלול המוביל את ישראל להתמזגות עם שאיפותיה של סין באזור, אלא דווקא כמאמץ לרצות את בייג’ינג בנושאים החשובים לה ולאזרחיה, כאשר בו בזמן ישראל מסייעת בתחום הצבאת למדינות אסיה החוששות מפני שאיפותיה של סין. על רקע זה, מאמץ זה צריך להיתפס בארה”ב כאסטרטגיה נבונה, שבסופו של דבר משרתת גם את האינטרסים של ארה”ב. זאת, שהרי גם בעידן הקיטוב הנוכחי, ממשל טראמפ, כמו קודמיו, למד להבין שסין היא יריב קשה במובנים מסוימים, אך גם שותף מועיל במובנים אחרים.

בסופו של דבר, מון הראוי להודות שתקפותם של טיעונים אלה תלויה בקריטריון חשוב אחד, והוא יכולתם של הסינים בישראל, בין כמשקיעים, כבוני תשתיות, או אפילו כסטודנטים, לנצל לרעה את שהותם בישראל לצורך השגת גישה למערכות רגישות, הנחת יסודות לחתרנות סייבר, והשגת מידע בדבר יכולותיהן של ישראל וארה”ב. כפי שכבר ציינתי, החשש הוא לגיטימי לחלוטין, בהתחשב ביכולת הסייבר ההתקפית של סין ובהיסטוריה הארוכה שלה בשימוש לרעה בזכויות יוצרים Intellectual Property) ). זהו בהחלט תחום שבו מומחים מארה”ב ומישראל צריכים לשתף פעולה באופן גלוי ונמרץ ביותר. למרבה המזל, המנגנון שמאפשר זאת כבר קיים; ויתרה מזאת, ישראל שומרת על יתרון ביכולות הסייבר ההגנתיות שלה, וניתן לנצל יתרון זה באופן מיטבי כדי לקבוע את הגבולות המתאימים לחדירה הסינית.

יש צורך בגישה מתוחכמת ומבדלת, שתיקח בחשבון את התועלת העיקרית שישראל עשויה להפיק ממעורבות גדולה יותר של סין במזרח הים התיכון (מעל לכול, במצרים), וגם את היתרונות הכלכליים הישירים של שיתוף פעולה ואולי אף הסכם סחר חופשי עם סין. אך בה בעת יש לבנות ולתחזק “חומה סינית” כנגד האפשרות שסין תנצל את הקִרבה הזו לרעה. זה בוודאי עדיף על פני גישה של “הכול או לא כלום”.

ייתכן שחלק מהפתרון מצוי בחיזוק הקשרים בין ישראל ובין מחוזות מסוימים בסין, שמטבע הדברים יתמקדו בצרכים אזרחיים לגיטימיים. ואכן, ב-1 בנובמבר 2018 הגיעה לישראל משלחת בראשותו של סגן מושל מחוז יונאן, צ’ונג גואויינג, לכנס השנתי הרביעי לחדשנות ולשיתוף פעולה בין מחוז יונאן שבסין לבין ישראל. קשרים דומים נוצרו גם עם מחוזות אחרים בסין. סוג זה של שיתוף פעולה, המיושם בזהירות, אינו צריך להיתפס כקריאת תיגר על מדיניותה של ארה”ב, אלא ככלי עזר העשוי לשרת אותה. במקביל לכך, יחסיה הביטחוניים של ישראל עם שחקניות מפתח אחרות במאזן הכוחות של אסיה ממשיכים להתפתח במהירות, ותורמים גם הם ליציבות ולאינטרס האמריקני במרחב. .

סדרת הפרסומים “ניירות עמדה” מטעם המכון מתפרסמת הודות לנדיבותה של משפחת גרג רוסהנדלר.

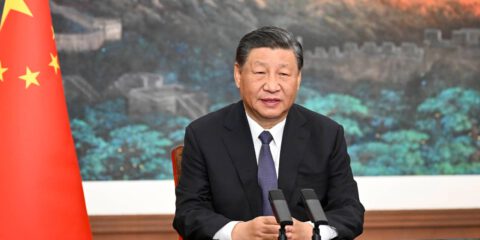

תמונה: Bigstock

- בניית אתרים

- בניית אתרים