Executive Summary

Critical minerals have emerged as one of the central fault lines of twenty-first-century geopolitics. Once treated as commercially neutral inputs governed by price signals and comparative advantage, minerals such as lithium, rare earth elements, nickel, cobalt, and graphite are now widely recognized as strategic assets underpinning national security, technological leadership, and industrial resilience. The United States’ decision to elevate critical minerals to the ministerial level reflects a broader reassessment: supply chains are no longer passive economic structures, but active instruments of power, vulnerability, and alignment.

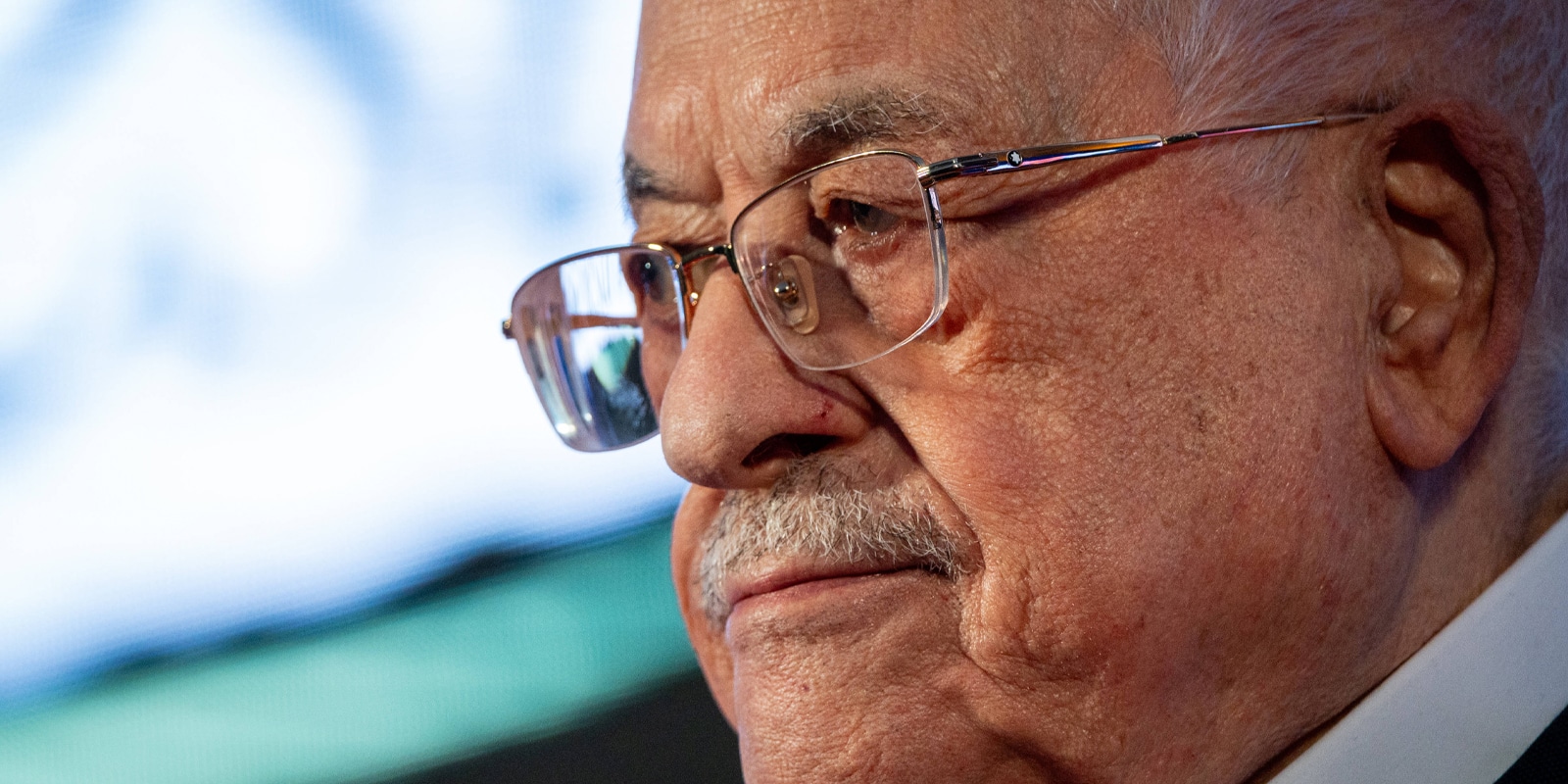

This paper argues that the U.S. initiative to build a network of trusted partners in the critical minerals domain—illustrated most clearly by the Critical Minerals Ministerial convened in Washington in February 2026 under the leadership of the U.S. Department of State, in coordination with the Department of Energy—is best understood not as a narrow containment strategy against China, but as a broader effort to construct a resilient, values-based supply-chain architecture. The ministerial brought together dozens of allied and partner countries, including Israel, which was represented by Foreign Minister Gideon Sa’ar. Within this emerging architecture, Israel occupies a distinct and under-appreciated role. While Israel is not a major producer of critical minerals, it is a strategic enabler across the value chain—particularly in advanced processing technologies, material science, recycling, digital optimization, and supply-chain security.

The paper further contends that Israel’s strategic relevance is amplified by its convergence of interests and values with key Indo-Pacific democracies—India, Japan, and South Korea. These countries combine advanced industrial bases, high exposure to mineral supply disruptions, and democratic governance systems that privilege transparency, reliability, and rules-based cooperation. Together, they form a community of states whose cooperation in critical minerals reflects both shared interests and shared political norms.

By positioning itself as a technological hub, regulatory innovator, and strategic connector between Europe, the United States, and Asia, Israel can play a pivotal role in shaping the architecture of allied mineral security. Doing so would not only enhance Israel’s strategic value to its partners but also anchor it more deeply within the emerging international order defined by strategic interdependence among democracies.

1. Critical minerals as a strategic domain

The strategic elevation of critical minerals reflects a deeper transformation in the nature of power. Advanced economies are increasingly dependent on technologies—electric vehicles, renewable energy systems, semiconductors, data centers, aerospace platforms, and advanced weapons systems—that are mineral-intensive rather than labor-intensive. In contrast to the industrial age, where energy and manufacturing capacity were decisive, the contemporary economy rests on complex material inputs whose absence can cripple entire sectors.

What makes critical minerals particularly sensitive is not scarcity per se, but concentration. While geological reserves are dispersed across continents, processing, refining, and mid-stream capabilities are heavily centralized. These stages, rather than extraction itself, constitute the true choke points of the global system. Control over them enables not only commercial advantage, but political leverage.

This reality has been reinforced by recent experience. Export restrictions, licensing requirements, and informal barriers have demonstrated how quickly supply chains can be disrupted for strategic purposes. As a result, critical minerals have joined semiconductors and energy infrastructure as domains where economic dependency translates directly into strategic vulnerability.

States are therefore no longer willing to rely solely on market mechanisms. The mineral sector is increasingly shaped by public policy instruments: subsidies, stockpiling, strategic financing, and alliance coordination. What is emerging is a new category of strategic infrastructure that is neither fully nationalized nor fully globalized, but embedded in networks of trust.

2. From globalization to strategic interdependence

The U.S.-led push for cooperation on critical minerals is part of a broader shift away from the assumptions that underpinned late-twentieth-century globalization. For decades, efficiency, cost minimization, and just-in-time delivery were treated as unqualified goods. Interdependence was assumed to be stabilizing by definition.

That assumption has collapsed under the weight of geopolitical reality. Asymmetric interdependence has proven to be a source of leverage rather than restraint. When supply chains are concentrated, dependence becomes coercible.

The response, however, is not economic nationalism or autarky. The scale, complexity, and capital intensity of mineral supply chains make self-sufficiency unrealistic for all but a handful of states. Instead, Washington is advancing a model of strategic interdependence: diversified supply chains embedded within a trusted network of partners sharing compatible political systems, regulatory cultures, and security interests.

This model relies on redundancy rather than exclusivity, coordination rather than centralization. It accepts higher costs in exchange for resilience and predictability. Crucially, it also recognizes that strategic contribution is not limited to resource ownership. States that lack raw materials can nonetheless provide indispensable capabilities elsewhere along the chain.

This logic opens space for countries such as Israel to play a role disproportionate to their size or geology.

3. Israel’s added value: technology, security, and resilience

Israel’s relevance to critical mineral security does not lie underground, but across the upstream and downstream segments where allied supply chains are most fragile.

First, Israel possesses advanced capabilities in materials science, chemical engineering, and process optimization. Israeli firms and research institutions are at the forefront of technologies that improve recovery rates, reduce waste, and lower the environmental footprint of mineral processing. These innovations are essential for making alternative processing hubs economically viable outside established monopolies.

Second, Israel has developed significant expertise in recycling, urban mining—that is, the recovery of critical minerals and metals from industrial waste, end-of-life products, and existing infrastructure—and in circular-economy solutions. As demand for critical minerals continues to grow, such secondary sources are becoming an increasingly important component of supply-chain resilience. As demand for critical minerals accelerates, secondary sourcing will become increasingly important. Israel’s experience in maximizing efficiency under conditions of scarcity provides a natural comparative advantage in this domain.

Third, Israel’s digital and cyber capabilities address a growing vulnerability in mineral supply chains: their exposure to disruption, espionage, and sabotage. As logistics, processing, and inventory systems become digitized, supply-chain security becomes inseparable from cybersecurity. Israel’s leadership in this field is directly relevant to allied efforts to protect critical infrastructure.

Finally, Israel brings a strategic culture shaped by operating under permanent security constraints. This translates into an instinctive emphasis on redundancy, risk management, and resilience, precisely the mindset now required for governing critical supply chains in an era of geopolitical competition.

4. A community of values and interests: Israel, India, Japan, and South Korea

Israel’s role is magnified by its convergence with key Asian democracies that occupy a central position in global manufacturing and technology.

India, Japan, and South Korea share several defining characteristics with Israel. All are innovation-driven economies with limited natural resources relative to their industrial needs. All are acutely exposed to supply disruptions in critical minerals. All operate in strategic environments shaped by regional power competition. And all seek technological sovereignty without rejecting global integration.

These shared conditions have driven deepening cooperation across defense, technology, and industrial policy. In the critical minerals domain, this alignment creates opportunities for complementary specialization: India’s scale and upstream potential, Japan and South Korea’s industrial processing capacity, and Israel’s technological and security expertise.

Beyond material interests, there is a normative dimension. These countries are democratic systems that value rule-based trade, transparency, and predictable regulation. Their cooperation is therefore not merely transactional but anchored in a shared understanding of how economic power should be exercised.

In this sense, cooperation among Israel, India, Japan, and South Korea represents more than a functional arrangement. It is the expression of a community of values that reduces political risk and enhances long-term strategic trust.

5. Israel as a strategic connector in allied architectures

Israel’s geographic position, diplomatic reach, and technological ecosystem allow it to function as a connector between regional and thematic frameworks that do not always align naturally.

For Europe, Israel offers technological solutions to a problem Europe cannot resolve through extraction alone. Europe’s regulatory and environmental constraints limit mining expansion, increasing the importance of processing efficiency, recycling, and digital optimization—areas where Israel excels.

For Asian partners, Israel provides access to a dense innovation ecosystem and security expertise aligned with Western standards. For the United States, Israel acts as a force multiplier, reinforcing allied coherence without duplicating industrial capacity.

This connector role is not incidental. It reflects Israel’s broader strategic interest in embedding itself within durable coalitions rather than transactional alignments. As global politics become increasingly structured around competing systems rather than isolated disputes, such embeddedness becomes a long-term asset.

6. Strategic implications

Engagement in the critical minerals architecture offers Israel strategic dividends that extend well beyond the mineral sector itself.

It reinforces Israel’s relevance in domains that define the future of power: advanced manufacturing, energy transition, AI, and defense technology. It anchors Israel within the core strategic priorities of its principal allies. It creates new avenues for industrial cooperation, technological export, and diplomatic alignment. And it positions Israel as a contributor to global public goods defined by resilience rather than dependency.

At the same time, this engagement requires conceptual clarity. Israel should not present itself as a substitute supplier, but as an enabler of allied resilience. Its comparative advantage lies in multiplying the effectiveness of others by lowering risk, improving efficiency, and enhancing security, rather than competing with resource-rich states.

The geopolitics of critical minerals thus illustrate a broader transformation in the international system. Power is increasingly exercised through networks rather than territory, through resilience rather than dominance, and through alignment rather than coercion.

In this emerging order, Israel’s strategic value lies not in what it extracts, but in what it enables. By contributing technology, security, innovation, and strategic connectivity, and by deepening cooperation with partners such as India, Japan, and South Korea, Israel can play a disproportionate role in shaping the architecture of allied supply chains. Critical minerals are therefore not merely an economic issue for Israel, but a strategic opportunity to reinforce its position within a U.S.-led international system built for an era of sustained great-power competition.

JISS Policy Papers are published through the generosity of the Greg Rosshandler Family.