Introduction

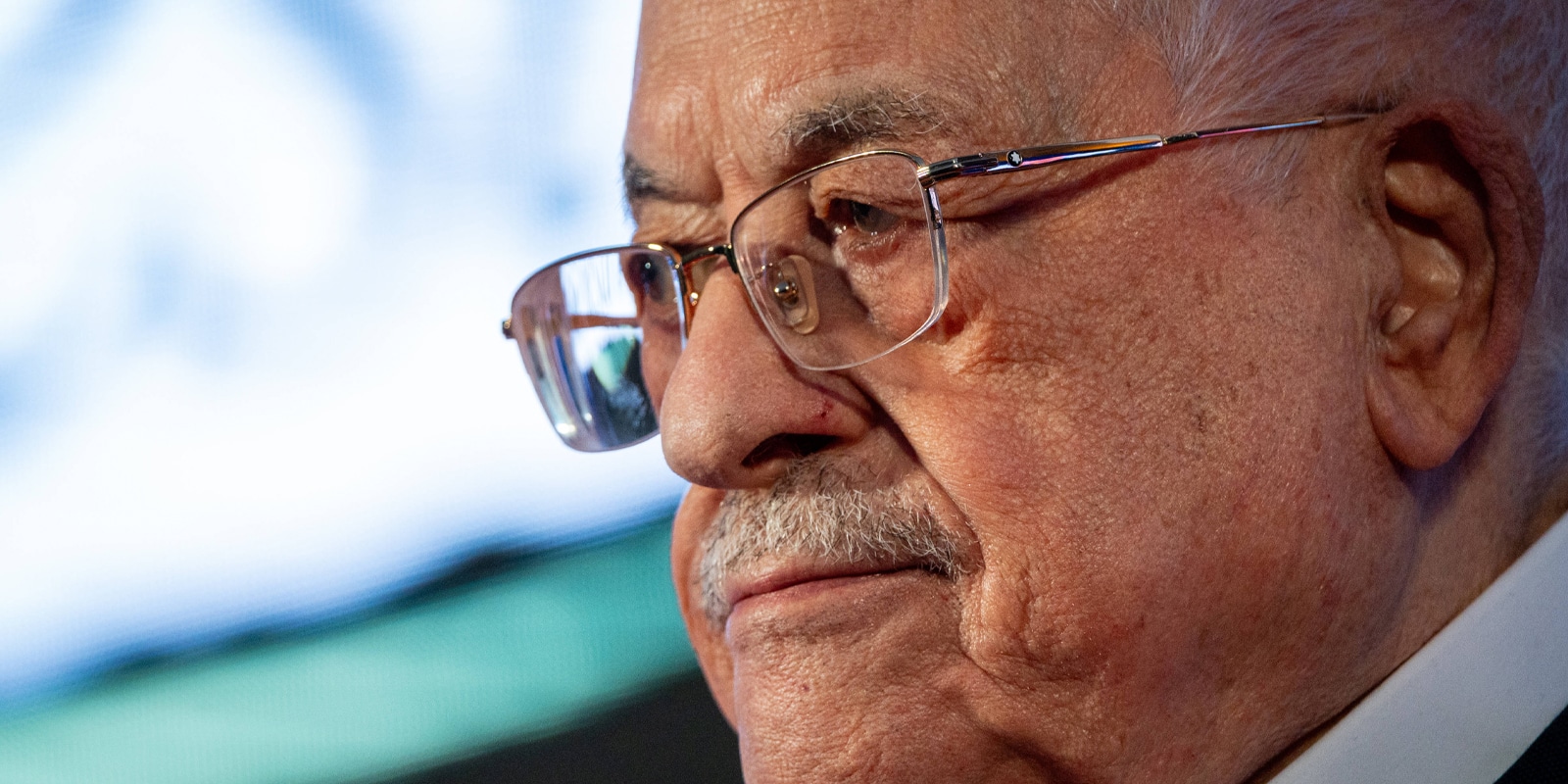

Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas’s (Abu Mazen) hospitalization for medical tests in January 2026 provides an opportunity to reassess Israel’s security strategy in Judea and Samaria. For years, Israel’s defense establishment has been mired in the concept of “strengthening the Palestinian Authority.” It has devoted thousands of hours to designing concessions, benefits, and preferential treatment for senior PA officials and their families. Prominent inciters, including Jibril Rajoub, were granted travel permits and broad freedom of movement. They spent time in Tel Aviv and traveled abroad while exploiting their own public and extracting substantial commissions from international aid funds.

Reality on the ground shows that although the Palestinian Authority still offers certain security advantages and continues to administer daily life for Palestinians in Judea and Samaria, it has largely become a security burden rather than a strategic asset. This article outlines the central security challenges posed by the PA and characterizes it as an entity that supports terrorism and incites against Israel; it then proposes policy directions for addressing both current and emerging threats, primarily through expanding counterterrorism and weapons-smuggling interdiction efforts, strengthening deterrence through more effective punitive measures, building operational readiness for the possibility of mass unrest and potential disorder within the PA, and establishing security buffer zones adjacent to Israeli communities and along the seam line—particularly in anticipation of the leadership vacuum likely to follow Abu Mazen’s departure.

The Palestinian Authority as a Security Liability

Since the Oslo Accords (1993–1995), the Palestinian Authority has failed to establish a functioning governing framework. Instead, it has evolved into a corrupt body that incites and supports terrorism. One of the central problems is its policy paying stipends to the families of imprisoned terrorists (“Pay-for-Slay”). The system is structured on a graduated scale tied to the severity of the attack: the longer the prison sentence, the higher the monthly payment. Despite reports of supposed reforms, the policy has continued in practice, even during periods of economic crisis. Abu Mazen publicly stated that he would allocate the PA’s “last penny” to the families of “martyrs.”

This mechanism reinforces a culture that glorifies terrorism and encourages further attacks. These payments are not just financial assistance; they constitute formal recognition of the legitimacy of terrorist acts against Israel. The message is explicit: killing Jews is treated as a sanctioned act that merits reward from the PA. Under the law that governs these salaries, imprisoned terrorists are defined as the “fighting sector” of Palestinian society and are therefore entitled to wages and additional benefits.

In 2025, under international pressure, Abu Mazen attempted to create the appearance that the payment mechanism had been abolished and that stipends would instead be distributed according to economic need. In practice, however, the change proved cosmetic. The payments have continued through alternative channels.

The Authority also operates systematically against Israel in the international arena. It files complaints against Israel in United Nations institutions, petitions the International Court of Justice in The Hague, and conducts a broad diplomatic campaign to secure recognition of Palestine as a state and to legitimize actions against Israel. It uses its diplomatic standing to promote boycotts and to undermine Israel’s international position.

More than three decades after the Oslo Accords, Palestinian incitement against Israel has not ceased. The Palestinian education system continues to teach successive generations to reject Israel’s legitimacy and to deny its right to exist as a Jewish state. Despite Palestinian claims of textbook reform, materials remain replete with hostile content. Maps omit the State of Israel, and instruction centers on glorifying the “muqawama” (resistance) against the “occupation.”

Palestinian media reinforces the same message. Television channels regularly air programs that praise terrorists and encourage attacks. Official radio devotes extensive coverage to “the martyr heroes” and portrays acts of terrorism as heroism. Senior PA officials, including Jibril Rajoub and others, use similar rhetoric in their public statements.

The Threat

The most immediate threat comes from terrorist organizations operating in Judea and Samaria, led by Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad, along with local cells that also include Fatah operatives. These organizations are working to establish terrorist infrastructure in the area, smuggle weapons and military equipment, and carry out attacks against soldiers and civilians. They operate within civilian areas in order to conceal their activities and complicate the operations of Israeli security forces.

Hamas is working to develop significant military infrastructure in the area. A Hamas document seized in Gaza described plans by its operatives to invade communities in Judea and Samaria and along the seam line in a pattern similar to the October 7 attack. Hamas is attempting to establish local weapons-production networks, including the capability to manufacture rockets and explosive devices. There is no basis to assume that the motivation for this activity has diminished, as the organization seeks to replicate in Judea and Samaria the capabilities it built in Gaza, including attempts to dig underground—initially, at least, for the purpose of concealing equipment and capabilities.

Another serious scenario is one in which Palestinian Authority security forces turn their weapons on Israel. This scenario is not merely theoretical. The military training these forces undergo in Jordan, Egypt, Iraq, and Pakistan focuses on combat operations rather than civilian policing. Leaked documentation from training shows preparation for confrontation with the IDF and for the invasion of Israeli communities.

These threats are compounded by weapons smuggling. This occurs both along the Israel–Jordan border, which serves as a significant route for the transfer of weapons and advanced military equipment to Palestinians in Judea and Samaria, and through Arab criminal networks inside Israel. Weapons smuggled include small arms, explosives, drones, and even anti-tank weapons. These weapons enable terrorist organizations to improve their capabilities and carry out more sophisticated attacks. The use of drones to carry explosive charges, together with the increased availability of anti-tank weapons and standard military-grade explosive devices, constitutes a new and significant threat to security forces and to residents of the area.

Beyond the direct military threats, Israel faces a challenge of weakened governance across large parts of Judea and Samaria. This challenge is reflected in the takeover of parts of Area C, which is under Israeli control, reflected in widespread illegal construction, and in the operation of unlawful waste-burning sites that pollute the environment and effectively constitute environmental terrorism. The takeover of land is carried out with financial support from the European Union and from Western and Arab states, within what appears to be a deliberate policy of creating facts on the ground ahead of the establishment of a Palestinian state. The activity includes the construction of permanent structures, the paving of roads, and the development of infrastructure without coordination with Israeli authorities.

These threats are not new, but they have intensified over time. They become even more problematic in light of the Authority’s internal condition and the expected succession struggle following Abu Mazen’s departure from the scene. The 89-year-old Palestinian leader suffers from health problems and has no agreed successor, although he has appointed Hussein al-Sheikh as his deputy and has taken steps that may position him as a future replacement. This situation could produce internal chaos, during which different factions may seek to strengthen their positions, including through confrontation with Israel.

To these factors must be added the broad support for Hamas in Judea and Samaria, as reflected in every internal and external poll conducted among residents. It is not without reason that elections have not been held in Judea and Samaria for the past twenty years. As early as the 2006 elections, Hamas won a majority of seats in the Palestinian parliament.

Israel’s Security Doctrine in Judea and Samaria

An effective security doctrine in Judea and Samaria rests on two pillars: high-quality intelligence and full operational control of the area. Such control does not require a permanent military presence at every location. It requires unrestricted operational freedom for Israeli security forces throughout the territory. In practical terms, there must be no “safe havens” where the IDF refrains from operating.

Over the past two years, the IDF has intensified its operations in refugee camps and in northern Samaria—areas that until recently served as strongholds for terrorist organizations. Ongoing operations in places such as the Tulkarm and Jenin refugee camps have dismantled terrorist infrastructure and significantly reduced terrorist activity in those areas. These operations demonstrate the importance of sustained and determined military presence. When the IDF acts consistently and proactively in each area, terrorist organizations struggle to regroup and build capabilities. When it refrains from operating in certain areas, terrorist networks strengthen and attacks increase. This dynamic was evident after the 2005 withdrawal from northern Samaria and again in the years preceding the War of Renewal (Swords of Iron), when the IDF curtailed its activity in the area and left counterterrorism efforts to the Palestinian Authority’s security forces.

Improving security also requires the development of security buffer zones around Jewish communities and along major transportation routes. These areas would be cleared of Palestinian presence, and suspicious movement within them would prompt an immediate military response. Establishing buffer zones would enable early detection of threats and prevent many attacks. Experience shows that where effective buffer zones have been created, incidents of stone-throwing, Molotov cocktail attacks, and attempts to place IEDs have declined sharply. Determined military action, at times in coordination with local settlers, has generated effective deterrence and led to sustained calm.

Buffer zones should not be limited to areas inside Judea and Samaria; they should also extend along the seam zone. For example, establishing a security buffer area beyond the separation barrier opposite the community of Bat Hefer could make it more difficult for attackers to move quickly across the area and infiltrate Bat Hefer in a manner replicating the October 7 events in the Gaza border communities.

Terror financing forms the backbone of hostile activity in Judea and Samaria. An effective counterterrorism strategy must therefore address the financial sources of terrorist organizations. This includes action against Hamas’s “dawa” network—a system of foundations and charitable organizations that channel funds to terrorist activity under a social and religious cover. It also requires intensified efforts against money changers who operated outside the formal banking system and facilitate the unmonitored transfer of funds to terrorist actors.

With respect to the Palestinian Authority, Israel must continue deducting from the funds transferred to the Authority the sums allocated to the families of terrorists. These deductions limit the financial resources available for terrorism and convey a clear message that financing terrorism carries a significant economic cost.

Israel must act decisively against illegal construction in Area C and prevent the takeover of open areas and the operation of unlawful waste-burning sites that pollute the air and water sources. This effort requires the allocation of substantial enforcement resources, rapid and effective action, and the advancement of legislation that enables economic sanctions against those involved, including the confiscation of vehicles used for illegal activity. Delay and hesitation in enforcement encourage continued violations and steadily undermine Israeli control and governance across large areas. The government and the military have recently begun to address the issue, and that effort should be expanded.

Preventing the smuggling of weapons and military equipment requires a substantial reinforcement of security along the Jordanian border, including the deployment of advanced surveillance systems, increased patrols, and the development of real-time interdiction capabilities to prevent cross-border smuggling. At the same time, Israel must act decisively against criminal smuggling networks within its territory that transfer weapons to Palestinians. This effort requires close cooperation with Jordan and with other regional states. Jordan, which is concerned about the spillover of terrorism into its own territory, has an interest in countering these smuggling routes, provided the cooperation is conducted with appropriate discretion.

Effective deterrence against terrorism requires a rapid, firm, and severe response to every terrorist attack. Such measures include the demolition of the homes of terrorists and their families, movement restrictions, and the revocation of economic permits. The current procedure, which allows petitions to the High Court of Justice and compromises such as sealing rooms instead of carrying out full demolition—measures intended to enable external review, prevent errors, and mitigate international criticism—has proven ineffective and fails to generate sufficient deterrence. Genuine deterrence exists when the personal cost of carrying out or assisting in a terrorist attack is both punitive and immediate. Achieving this requires legislation that prioritizes the right to life of Israeli citizens over the property rights of terrorists’ families and permits the prompt execution of demolition orders without unnecessary bureaucratic delay.

Finally, action must be taken against incitement to terrorism, which constitutes a serious offense that requires an immediate and severe response. Senior Palestinian officials engaged in incitement must be identified and confronted; including through a review of the rights and benefits they receive. The situation in which figures such as Jibril Rajoub are granted travel permits within Israel while continuing to incite against the State of Israel is untenable.

Action should also be taken against incitement in the Palestinian education system. Israel can condition economic assistance and the opening of crossings on removing inciting content from Palestinian textbooks. It is also important to explain this issue clearly, especially to the states and organizations that fund PA’s education system. The closure of UNRWA and President Trump’s reduction in UN funding present an opportunity, alongside implementation of the government decision governing which organizations are allowed to operate on the ground.

Scenarios for the Post–Abu Mazen Era

Abu Mazen may step down from leadership of the Palestinian system in the relatively near term. His departure could create a leadership vacuum and lead to chaos. Although Abu Mazen has prepared the ground for a succession process that would place authority in the hands of Hussein al-Sheikh, he lacks the means to secure support from all power centers within Fatah, let alone outside it. There is therefore no clear successor, and rival candidates are engaged in an internal struggle. This situation could result in fragmentation within the PA, internal confrontations, and attempts by competing groups to consolidate their position, including through attacks against Israel. Israel must prepare for this possibility and plan its response in advance. That preparation should address the potential need to take over the PA’s civilian administration, contingency plans for temporary military control in areas where order breaks down, and the possibility of increased emigration by Palestinians seeking to leave the area.

If the Palestinian Authority collapses, even if only in some cities, Israel may be required to reestablish military administration in areas of Judea and Samaria. This outcome would be politically and economically undesirable, but Israel must be prepared if circumstances demand it. Planning for this scenario must include arrangements to provide basic services through existing systems operated by Palestinian technocrats and to maintain public order. Any temporary military administration should be time-limited and include the broadest possible civilian component. The objective would be to prevent chaos and allow responsible Palestinian leadership to reorganize while safeguarding Israel’s security interests.

Finally, the “emirates” alternative warrants consideration. Instead of a centralized Palestinian Authority, governance could shift toward locally based emirates or forms of municipal self-rule. Such a framework would depend on local leadership not committed to Palestinian national ideology and more focused on economic development and residents’ quality of life. Experience in Iraq and elsewhere shows that local governance can, at times, be more stable than centralized rule. Implementing such a structure would require identifying and preparing suitable local leaders and establishing the necessary economic and legal frameworks. The power structures in each city are already well understood, allowing this alternative to be advanced immediately.

Challenges and Constraints

Implementing the proposed security doctrine entails a complex set of challenges—some technical and logistical, others political and diplomatic, and still others domestic and social within the Palestinian arena. These are not merely tactical obstacles. They reflect an inherent tension between immediate security requirements and their long-term implications for Israel.

Required Resources

Sustaining continuous and proactive operational control across Judea and Samaria—including ongoing operations in refugee camps, enforcement against illegal construction, and reinforcement of the Jordanian border—requires a substantial and sustained allocation of forces. According to IDF data, Palestinian terrorist incidents in Judea and Samaria declined by roughly 80 percent in 2025 as a result of intensive activity by the IDF and the Shin Bet. However, it requires dozens of brigade-level operations, the mobilization of thousands of reservists, and significant resources.

The burden is growing heavier as Israel must simultaneously maintain high readiness on other fronts (Lebanon, Syria, Gaza, and Iran). Effective enforcement in Area C also requires expanded civilian-administrative capacity—inspectors, engineers, and police personnel—at a time when Israel faces a persistent shortage of trained manpower in these fields.

The International Arena

Wide-scale military operations, building demolitions, the establishment of security buffer zones, and expanded enforcement in Area C routinely draw sharp criticism from European Union member states, certain Western governments, and UN bodies. The European Union denounces what it terms “settlement expansion” and has accused Israel of “undermining regional stability,” including calls for sanctions and the suspension of trade agreements. So far, such proposals have been blocked. France, the United Kingdom, Canada, and others have issued joint statements opposing the approval of new settlements, including the nineteen communities approved in December 2025.

The risks extend beyond diplomatic censure. Proceedings at the International Court of Justice in The Hague could advance, boycotts could intensify, and economic measures may follow, including the labeling of products from settlements or restrictions on research and technological cooperation. At the same time, past experience suggests that the international community tends to adjust to facts on the ground when they are accompanied by consistent public explanation and credible security rationale—particularly in light of the marked decline in attacks resulting from sustained and determined Israeli control.

Domestic Israeli Constraints

Implementing the proposed security doctrine in Judea and Samaria—continuous operational control, firm enforcement against illegal construction, home demolitions for the purpose of deterrence, security buffer zones, and economic pressure against terrorist infrastructures—requires sustained and close coordination among several core institutions: These include the defense establishment (the Ministry of Defense, the IDF, Central Command, the Shin Bet, the Civil Administration, and the Israel Police), civilian authorities (the Knesset, planning bodies, and tax authorities), and the legal system (the Military Advocate General, the Attorney General, the High Court of Justice, and military courts).

When coordination falters or decisions are delayed, operational gaps emerge. The Palestinian Authority, internationally funded NGOs linked to the PA and to Palestinian terrorist organizations, exploit those gaps quickly and effectively.

Home demolition policy illustrates the problem. It is intended as a key deterrent tool, yet in practice it is frequently delayed by petitions to the High Court of Justice. Temporary and interim injunctions can suspend demolition orders, even in cases involving major attacks. As a result, deterrence is significantly weakened. The perpetrator and those around him understand that the process may take months, and at times years, reducing the immediacy of the personal cost and weakening the link between the act and its consequences.

The Civil Administration, which oversees civilian enforcement in Area C—including illegal construction, waste-burning sites, and land seizures—operates under a high evidentiary threshold and intensive and tendentious judicial scrutiny. As a result, immediate military actions—such as closing an area or carrying out a tactical demolition—often face objections or are delayed by civilian and legal authorities.

In sum, domestic constraints stem from structural and legal misalignment between systems that operate according to different institutional logic. Addressing this gap requires not only operational decisions but also institutional reform that enables a faster, coordinated, and decisive response. Without such changes, even a well-designed security doctrine risks remaining largely declarative or being implemented only partially.

Conclusion

The security reality in Judea and Samaria requires a comprehensive strategic approach that addresses current threats while preparing for future challenges. In its present condition, the Palestinian Authority constitutes more of a security liability than an asset. Israel must prepare for a range of scenarios in the event of Abu Mazen’s departure, including the possibility of the collapse of the PA and its replacement by an alternative framework, such as an “emirates model.”

The doctrine we propose rests on three principles: full operational control of territory, control over the financial flows that sustain terrorism, and the establishment of effective deterrence against hostile activity. At the same time, Israel must prepare for future scenarios and develop alternatives to the current situation.

The success of this approach depends on determined implementation, the allocation of necessary resources, and a long-term strategic outlook rather than the pursuit of short-term quiet. Israel must act in accordance with its security interests, not in response to external pressure or apprehension, while keeping in view the broader objective of peace through strength and a more stable long-term security environment.

Time will work in Israel’s favor only if it acts decisively and takes the initiative. Delay and hesitation risk worsening the situation and allowing new and more serious threats to emerge. The Abu Mazen era is nearing its end, and Israel must be ready to seize emerging opportunities and confront the challenges of the day after.

JISS Policy Papers are published through the generosity of the Greg Rosshandler Family.