המיליציות השיעיות העיראקיות מהוות רכיב שכוחו עולה, מתוך כלל הנכסים הצבאיים והצבאיים-למחצה העומדים לרשות איראן כחלק ממאמציה לבסס הגמוניה אזורית. נכסים אלו עלולים להעצים באופן משמעותי את יכולותיה במקרה של מלחמה בחזית הצפונית של ישראל.

תמונה: כרזה הנושאת את הלוגו של כוחות הגיוס העממי ואת פניו של המנהיג העליון האיראני – עלי ח’מינהאי, במטה כוח באדר, בגדד, יולי 2015 (צולם בידי יונתן ספייר).

מבוא

“על המשטר האיראני לכבד את ריבונות הממשלה העיראקית ולאפשר את פירוק המיליציות השיעיות מנשקן”, הזהירה מחלקת המדינה האמריקאית ב-30 באוקטובר 2018, כחלק מן הצעדים שעל איראן לנקוט אם ברצונה להימנע מחידוש הסנקציות.

איש לא הופתע כשטהראן לא נענתה לאזהרה. המיליציות השיעיות בעיראק הן אחד מאמצעי מדיניות החוץ האפקטיביים ביותר של איראן. יחד עם ישויות “פרוקסי” זוטרות בשטחים הפלסטינאים ובקרב הקהילות השיעיות במפרץ הקימה איראן את ארגון חיזבאללה בלבנון; ארגון חזק המהווה איום רציני על ישראל ועל היהודים ברחבי העולם, ומשמש אף כשחקן ההופך יותר ויותר פעיל ברחבי המזרח התיכון. המלחמות בעיראק ובסוריה, והסכסוכים האתניים הנלווים, אפשרו לאיראן ליצור ארגונים שיעיים מזוינים. מיליציות שיעיות מובילות אחדות, אומנם באיכות משתנה, הוכחו זה מכבר כבעלות יכולת, נאמנות ומסוכנוּת. ארגונים אלו הפכו לאמצעי חדש עבור איראן המסייע לה להרחיב את השפעתה, לפעול נגד האינטרסים האמריקאים ולהכין את הקרקע לקראת איומים חדשים על ישראל.

במבט ראשון נראה כי המיליציות השיעיות הן גורם שישראל יכולה להרשות לעצמה להתעלם ממנו. הן פועלות הרחק מגבולותיה של ישראל, והיו מעורבות בלחימה בסונים ולא במדינת היהודים.

אך תהיה זו טעות מצידה של ישראל להתעלם מהאיום המתעצם. לאחר נפילת דאע”ש ושליטתה החלקית של איראן על הרצף הטריטוריאלי שבין איראן לחופי לבנון – ובייחוד לאור נסיגתה המתוכננת של ארצות הברית – טהראן ובעלות בריתה מפנות תשומת לב הולכת וגוברת לישראל. בדצמבר 2017 ביקר מנהיג המיליציה השיעית העיראקית, קייס אל-חזאלי, בכפר כילא השוכן סמוך לגבול ישראל-לבנון.

“אני כאן עם אחיי מחיזבאללה, ההתנגדות האסלאמית”, הצהיר חזאלי. “הכרזנו על מוכנות מלאה לעמוד כגוף אחד עם הלבנונים, לתמוך במטרה הפלסטינית, לאור הכיבוש הישראלי הבלתי הוגן, שהינו אנטי-אסלאמי, אנטי-ערבי ואנטי-האנושות, ולתמוך במטרה הערבית-מוסלמית המוחלטת”.1

באוגוסט 2018 החלו לצוץ דיווחים על כך שאיראן מעבירה טילים בליסטיים למיליציות שלה בעיראק, ומסייעת להן לפתח יכולות לייצור טילים. טילים אלו, בעלי טווח של 200–700 קילומטרים, עלולים לשמש בהתקפה נגד ישראל וערב הסעודית מתוך שטח עיראק.2

ככל שהאיום גובר, ההנהגה הישראלית מוכרחה להכיר באתגר, להעמיק את הבנתה בכל הקשור למיליציות וליכולותיהן ולפתח תגובות הולמות. עבודה זו נועדה להוות צעד בכיוון זה. העבודה עוסקת בשימוש שעושה איראן בלוחמת פרוקסי (“על ידי שליח”), בוחנת את המיליציות השיעיות המובילות, מפרטת את המערכות שלהן ואת כוחן העולה במערכות הפוליטיות. כמו כן, העבודה מציגה את השלכות פעולותיהם של ארגונים אלה על הביטחון הלאומי של מדינת ישראל.

לוחמת הפרוקסי של איראן

משחר ההיסטוריה היוותה לוחמת פרוקסי אמצעי בסכסוכים מזוינים, ואיראן משתמשת בהצלחה רבה באמצעי זה מאז ימי המהפכה האסלאמית.3

השימוש בישויות פרוקסי מזוינות, ובכלל זה המיליציות שלה בעיראק ובסוריה, מאפשר לטהראן להסב נזק ליריבותיה תוך צמצום עלויות, ולשמר רמה מסוימת של יכולת הכחשה. הוא גם חסכוני; מדוע לשפוך דם איראני כשניתן לשפוך דם ערבי, פקיסטני ואפגאני? מיליציות זרות מהוות גם אינדיקציה לנטייה העל-לאומית של המהפכה האסלאמית, המחזקת את המעמד הבינלאומי של איראן ואת התביעה שלה למנהיגות פאן-אסלאמית. הנחישות של איראן, הכישרון שלה ליצירת ישויות פרוקסי שונות והמוכנות שלה לשלוח אותן למקומות מסוכנים, הוכחו כאחד היתרונות המשמעותיים ביותר של הרפובליקה האסלאמית נגד מתנגדיה הסונים והמערביים.

המודל האיראני של לוחמת פרוקסי נשען על שלושה יסודות: תחושה של קהילה שיעית משותפת, הנוכחות האיראנית השיעית המהפכנית בקהילות אלו וזיהוי של אויב ברור ומשותף שעימו איראן מעוניינת בחיכוך כדי להכיר ולהעריך טוב יותר את היכולות שלה.

הצלחתה של איראן ביצירת ישויות פרוקסי מתבססת על הקהילה המשותפת עם ישויות שיעיות אחרות. מושג הקהילה מייצג סדרה עמוקה ומהותית של קשרים – תרבותיים, דתיים, משפחתיים וחווייתיים. זהו הרעיון כי החברים בקהילה יימצאו לנצח באותו צד ויחלקו גורל משותף. הבעיות של חלק מחברי הקהילה הן למעשה בעיותיה של הקהילה כולה. משמעות הקשר הקהילתי היא שהפטרון והפרוקסי חשים ביטחון בכך שכולם מחויבים למאבק לטווח הארוך. בעבר, איראן זנחה את ההאזארים באפגאניסטן כשהללו נפלו קורבן לטאליבן; אך כעת טהראן מרגישה חזקה יותר ומוכנה להתערבות במקרים שבהם נסיבות כאוטיות מאיימות על הקהילות השיעיות.

בקרב הקהילה השיעית, מאמציה ארוכי הטווח של איראן ליצור ישויות פרוקסי מתבטאים תחילה בנוכחות. נוכחות זו עשויה לכלול תנועות נוער, בתי ספר דתיים, שירותים חברתיים, אימונים צבאיים ועוד, הרבה לפני שעולה הצורך להקים קבוצות מזוינות. הנוכחות הזו מסייעת לאיראן ליצור מערכות יחסים עם מנהיגים פוטנציאליים, שרבים מהם לחמו לטובת איראן או התאמנו באיראן, יחסים שאפשר למנף ולהרחיב ברגע שבו איראן תהיה מעוניינת ליצור כוח פרוקסי משמעותי. הנוכחות ארוכת הטווח של איראן נשענת אפוא על קיומן של קהילות שיעיות באזורים שבהם היא מעוניינת בהשפעה.

איראן איננה מצטיינת בחיזוי העתיד יותר מכל פטרון אחר, ועל מנת לשמר הבנה רלוונטית של המציאות המשתנה איראן מבקשת ללמוד באמצעות מגע או חיכוך עם האויב. שיטת למידה זו מצריכה סכסוך מתמשך עם יריבות על מנת להעריך את יכולותיהן, שיטות הפעולה שלהן וכוונותיהן. איראן דוחקת בישויות הפרוקסי שלה ליצור מגע תכוף עם האויב על מנת לשמר את רמת החיכוך ולוודא כי הבנת האויב נשמרת ורלוונטית. גם לאחר הנסיגה מלבנון, בשנת 2000, לא ויתר חיזבאללה על חיכוך עם ישראל באמצעות תקיפות נקודתיות בגבול על מנת לוודא כי ההבנה לגבי ישראל וצה”ל עודנה רלוונטית. צעדים אלו תרמו ללמידה משותפת הן של חיזבאללה והן של הפטרון האיראני.

המודל בעל שלושת המרכיבים פעל היטב לטובת איראן ברחבי האזור, אך רק בתנאים מסוימים. במדינות חלשות בעלות אוכלוסייה שיעית משמעותית, כגון לבנון, סוריה ועיראק, טהראן מסוגלת ליצור ישויות פרוקסי אפקטיביות. במדינות יציבות יותר שיש בהן אוכלוסייה שיעית – ערב הסעודית ובחריין – איראן נאלצת לעבוד קשה יותר על מנת להשיג את מטרתה. באזורים כמו עזה, שבהם אין אוכלוסייה שיעית, איראן מנסה ליצור ישויות פרוקסי נאמנות ואפקטיביות בטווח הארוך באמצעים אחרים, כגון אספקת נשק באיכות גבוהה לג’יהאד האסלאמי הפלסטיני ושימוש במינוף האיראני כדי להגן על הארגון מפני לחצי חמא”ס.

איראן מבקשת לשלב את המאמצים הצבאיים, הדתיים והפוליטיים שלה ביצירת ישויות פרוקסי ובשימוש בהן. קמפיין ממוקד כזה הופך קל יותר בשל העובדה שהשימוש שאיראן עושה בישויות הפרוקסי נשלט באופן ריכוזי מאוד על ידי ארגון בודד – כוח קודס של משמרות המהפכה האיראניים. איראן איננה צריכה להילחם במערכת בירוקרטית משוסעת ומשתקת של סוכנויות ביטחון יריבות. יתר על כן, את כלל המאמצים הקשורים בישויות הפרוקסי מוביל אדם אחד – הגנרל קאסם סולימאני, המדווח ישירות למנהיג האיראני העליון. סולימאני מסוגל להבטיח את המשכיות התמיכה הפוליטית, הצבאית והפיננסית שעליה הוא נשען על מנת לשמר את ישויות הפרוקסי הרבות שיש לאיראן באזור. מנהיגי ישויות הפרוקסי נהנים ממערכת יחסים קרובה ואישית עם סולימאני. מאמץ רב-פנים ממוקד זה יוצר סינרגיה, אשר הוכיחה את עצמה כאפקטיבית ביותר בכל הקשור ליצירת ישויות הפרוקסי ולניהולן.

נראה כי יצירת מיליציית באסיג’, עם פרוץ מהפכת 1979, עיצבה את גישתה של איראן בכל הקשור ליצירת ישויות פרוקסי. מודל זה, שמתחיל בגיוס המוני של נוער מנוכר לטובת כוח טרום-שלטוני, שימש כבסיס ליצירת חיזבאללה, וכעת משמש בסיס ליצירת המיליציות השיעיות. ישויות הפרוקסי האיראניות יוצרות תחילה קבוצה פוליטית, לאחר מכן מיליציה דתית, ובסופו של דבר נאלצת הממשלה הלאומית להכיר במיליציה כחלק ממערך ההגנה הרשמי של המדינה.4

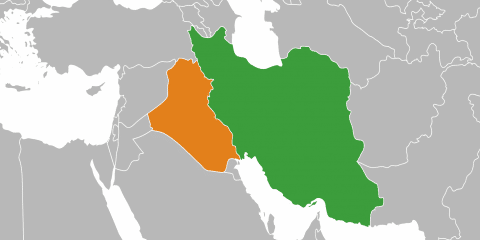

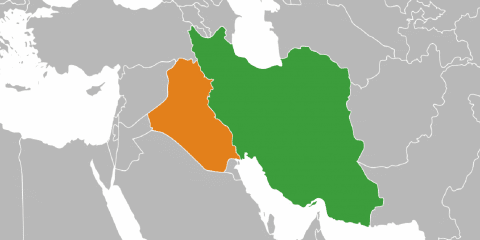

ישויות הפרוקסי של איראן בעיראק

האסלאם השיעי, שלו כ-200 מיליון מאמינים, מהווה למעלה מ-10% מאוכלוסיית המוסלמים בעולם. המדינה השיעית הגדולה ביותר היא איראן, עם 65 מיליון מאמינים, שהם 95% מהאוכלוסייה. עיראק היא שכנתה של איראן ובה השיעים מהווים רוב של למעלה מ-60%. בלבנון השיעים הם כשליש או יותר (נתונים סטטיסטיים בלבנון הם עניין פוליטי, ולא ניתן לדעת עד כמה הם מדויקים). החיבור בין השלטון השיעי באיראן לבין השיעים בעיראק מעוגן בקשרים גאוגרפיים, דתיים ואישיים.

הקהילה השיעית בעיראק נשענת על שלושה עמודי תווך. הראשון הוא הערים הקדושות לשיעים, נג’ף וכרבלא, שם נוצרה הזהות השיעית הדתית. העמוד השני הוא רשת השבטים השיעים בדרום עיראק אשר תלויים כלכלית בערים הקדושות. העמוד השלישי הוא השיעים העירוניים, שחלקם קשובים למסרים דתיים איראניים וחלקם דתיים אך מתנגדים למודל האיראני של ‘ולאית-י-פקיה’ (velayat-a-faqih) – שלטון המנהיג העליון. קבוצה נוספת היא קבוצת הלאומנים העיראקים החילוניים.5

השיעים בעיראק רחוקים מלהיות מאוחדים. שיעים עירוניים עניים הם לב התמיכה באמאם מוקתדא-אל-צדר, שהמיליציה שלו לחמה נגד הכיבוש שהונהג על ידי ארצות הברית. למרות העובדה שרכש את השכלתו באיראן, הוא הפך ליריב המיליציות הנתמכות בידי איראן בעיראק, התנגד לניסיונות איראניים לצרף אותו לשורותיהם ומציג עצמו כלאומן עיראקי מתון המייצג את המעמדות הנמוכים בעיראק.6 זכייתו של צדר ברוב יחסי של המושבים בבחירות שנערכו ב-2018 בעיראק הפתיעה את המשקיפים, והדאיגה הן את האמריקאים והן את האיראנים, המעריכים כי ינסה לפעול להגבלת השפעתם בעיראק.7

הדמות השיעית החזקה ביותר בעיראק הוא אייתוללה עלי סיסתאני הנערץ, לאומן עיראקי (אומנם ממוצא איראני, כפי ששמו מעיד) אשר קידם רפורמות בממשלה תוך התנגדות להשפעה איראנית בעיראק. סיסתאני סייע לראש הממשלה לשעבר, ח’יידר אל-עבאדי, לזכות בתפקיד ולהחליף את נורי אל-מאלכי, המקורב לאיראן.8 אולם, היה זה סיסתאני אשר חיבר את פסק ההלכה המוסלמי המפורסם בשנת 2014 הקורא לעיראקים להתנגד בכוח למדינה האסלאמית. קריאה זו הובילה ליצירת כוחות הגיוס העממי (PMU, ובערבית אל-חשד אל-שעבי), מערך של מיליציות שיעיות הנשלטות על ידי ארגונים בשליטת איראן.

לא כל המיליציות השיעיות בעיראק נאמנות לאיראן. המיליציות המובילות נשבעו אמונים למנהיג העליון של איראן, אייתוללה עלי ח’מינהאי, אולם יש מיליציות שנאמנות לסיסתאני, וכאלה הנאמנות לצדר. בעוד שהקבוצות הנאמנות לסיסתאני ולצדר מעדיפות לראות את PMU משולבים בכוחות המזוינים העיראקיים, או לחלופין מפורקים, המיליציות הח’מינאיסטיות הצליחו לשמור על עצמאות PMU באישור המדינה.9

הזהות הדתית של המיליציות הנתמכות בידי איראן ב-PMU נמצאת בבסיס כלל הפעילות שלהם. הם מניפים בגאווה דגלים הנושאים את פניהם של קדושים שיעים, ותולים כרזות עם פניהם של ח’ומייני וח’מינהאי. מיליציות אלו ואיראן חולקות לא רק זהות דתית משותפת, אלא גם אינטרסים דומים. עד לאחרונה הן ראו בדאע”ש את יריבתם העיקרית המאיימת על השיעים בעיראק, בסוריה ועוד. בנוסף, קהילות סוניות רבות בעיראק, ובייחוד אלו הקשורות למפלגת הבעת’ של צדאם, נתפסות כאויבות. בנוסף, חרף שיתוף פעולה נקודתי בין המיליציות לארצות הברית, ותיאום מוסווה של ארצות הברית עם איראן, הנוכחות האמריקאית איננה רצויה. כל שיתוף פעולה הינו זמני. בדומה לאיראן, המיליציות עוינות את הנוכחות האמריקאית ואת האינטרסים האמריקאים ארוכי הטווח.

המיליציה החזקה ביותר ב-PMU היא ארגון בדר. רבים מחשיבים ארגון זה לכוח הדומיננטי בעיראק כיום, לכל הפחות עד לבחירות ב-2018 שבהן הוא הגיע למקום השני. הארגון נוסד באיראן בשנות השמונים בידי שיעים עיראקיים שנמלטו מצדאם חוסיין ולחמו למען טהראן במלחמת איראן-עיראק. בראש ארגון בדר עומד האדי אל-אמירי, ששירת גם כשר התחבורה העיראקי. ארגון בדר שלט גם במשרד הפנים בעל הסמכויות הרבות.

בדומה לחיזבאללה בלבנון, לארגון זרוע פוליטית וזרוע צבאית הממומנת ומודרכת על ידי איראן. אמירי מכיר בתמיכה זו, ונחשב למנהיג העיראקי הקרוב ביותר לאיראן ולקאסם סולימאני.10 אולם הארגון “מדגים את הזהויות השונות שלו ואת המורכבויות המגדירות את קבוצות המיליציות השיעיות בעיראק”. תוך שמירה על יחסים אינטימיים עם טהראן, ארגון בדר שיתף פעולה עם ארצות הברית ועם המערב בפעילות צבאית נגד דאע”ש, והינו חלק בלתי נפרד ממערכת הביטחון העיראקית.11

על פי הערכות מסוימות ארגון בדר מונה כ-50,000 לוחמים, אך קרוב לוודאי שמדובר בכ-20,000 לוחמים.12 המיליציה, אשר מקיימת קשר הדוק עם IRGC – כוח קודס, התבלטה בקרבות נגד דאע”ש באזורי תיכרית, פלוג’ה ומוצול.

הארגון הואשם בביצוע פעולות אכזריות נגד הסונים בעיראק, ומחלקת המדינה האמריקאית אף טענה כי אחת מ”שיטות ההרג המועדפות על אמירי כוללת לכאורה שימוש במקדחה לניקוב גולגולות מתנגדיו”.13

ארגון PMU – כתאאב חיזבאללה (KH), המרכיב כרגע את הבריגדה ה-45 של PMU, נוסד לראשונה בשנת 2004 במטרה לתקוף את כוחות הקואליציה. KH נוסד בידי אבו מהדי אל-מוהנדיס, שיעי עיראקי אשר בילה עשורים מספר באימונים באיראן. הוא נדון למוות בכווית בשל מעורבותו בהתקפות הטרור ב-1983 נגד השגרירות האמריקאית והשגרירות הצרפתית כנקמה על תמיכתן בעיראק במלחמה נגד איראן בשנות השמונים. נטען כי מוהנדיס חולם ליצור גרסה עיראקית של כוח קודס האיראני,14 וכי הוא כרגע המנהיג השני בחשיבותו ב-PMU – אחרי אמירי. הארגון מאמין ב’ולאית-י-פקיה’ (velayat-a-faqih), המכירה בסמכותו של ח’מינהאי.

בדומה למפקדו, אמירי, למוהנדיס קשר קרוב ביותר עם סולימאני, והוא מתרברב בריש גלי בנאמנותו לאיראן. “כוחות הגיוס העממי לא היו מסוגלים לערוך מבצעים כה אדירים ללא תמיכת הרפובליקה האסלאמית של איראן, ובייחוד עלי ח’מינהאי, אשר הורה לכוח אל-קודס לתמוך ב-PMU ותומך בנו באמצעות הספקת נשק, תחמושת, ייעוץ ותכנון”, אמר מוהנדיס בשנת 2016.15

ארגון KH תקף באופן קבוע את הכוחות האמריקאים בעיראק, ולאחר הסכם הביטחון שנחתם בשנת 2008 בין ארצות הברית לעיראק החל לאיים גם על כוחות הביטחון העיראקיים. ארצות הברית רואה ב-KH ארגון טרור זר.16 למרות התבלטותו בקרב נגד דאע”ש ברמאדי, כארמה ותל-עפאר, ארגון זה קטן בהרבה מארגון בדר, וככל הנראה מונה כ-1,000 לוחמים בלבד. לארגון 10,000 לוחמים נוספים המאוגדים בישות הפרוקסי “פלוגות ההגנה העממית” (סראיה אל-דפאע אל-שעבי), ו-3,000 מתוכם מוצבים בסוריה.17

גם ארגון KH הביע נכונות לשיתוף פעולה מוסווה עם ארצות הברית, הכורדים והכוחות העיראקיים נגד דאע”ש. אולם, בדומה לארגון בדר, גם ארגון KH היה מעורב בעינוי וברציחת סונים, גם לאחר כיבוש פלוג’ה.18

בשנת 2006 התפצל ארגון עצאיב אל-חק (AAH) מתוך ארגון ג’יש אל-מהדי של צדר, והוביל אלפי תקיפות נגד מטרות אמריקאיות, מערביות וממשלת עיראק. בדומה לשותפו העיקרי, ה-PMU, ארגון AAH מנהל מערכת יחסים קרובה במיוחד עם איראן וחיזבאללה. הארגון מקבל כ-1.5–2 מיליון דולר מאיראן בכל חודש.19 כרזות של ח’מינהאי וחומייני תלויות במשרדי הארגון.20 איראן מממנת את הקבוצה על מנת לוודא כי תהיה לה אלטרנטיבה נאמנה יותר מתומכי צדר. גורמים אמריקאים תופסים את מיזם AAH כניסיון איראני לגבש גרסה עיראקית של חיזבאללה. “אני רואה אותם בראש ובראשונה כפרוקסי איראני. טבעם מצביע על כך שהם מעולם לא ויתרו על שאיפתם להפוך לאנלוגיה עיראקית לחיזבאללה”, טען אחד מן הגורמים האמריקאים.21

מפקדי חיזבאללה סיפקו הכשרה ללוחמי AAH, תחת חסותו של כוח קודס ושל קאסם סולימאני.22 הטקטיקות של AAH היו “טקטיקות קלסיות של סולימאני”, כולל תקיפות סתר והכחשת אחריות.23 הארגון התפרסם בשנת 2007 לאחר תקיפת מאחז אמריקאי בכרבלא, שהסתיים במותם של חמישה חיילים אמריקאים. בשנת 2008 נמלטו חברי AAH לאיראן לאחר שהצבא העיראקי כבש את שכונת צדר סיטי בבגדאד והחל לערוך שם אימונים צבאיים. בין השנים 2006–2011 טענו AAH לאחריות על למעלה מ-6,000 תקיפות על כוחות הקואליציה. כיום הארגון מונה כ-10,000 לוחמים, וכ-1,000–3,000 לוחמים מוצבים בסוריה. AAH תפס תפקיד מרכזי בלחימה בדאע”ש, בייחוד באזור דיאלא, אמרלי, תיכרית ומוצול. חרף ההתנגדות החריפה לארה”ב, הפך למעשה ארגון AAH לשותף לאמריקאים בכל הקשור בלחימה בדאע”ש.

ארגון AAH מונהג בידי קייס אל-חזאלי, אשר דיווח ישירות לסגן מפקד כוח קודס, עבדול רזה שהאלי, במהלך הלחימה נגד הכוחות האמריקאים.24 בשנת 2007 נשבו חזאלי, אחיו וחבר בכיר בחיזבאללה בידי כוחות מיוחדים בריטיים בקרבת בצרה, אך שוחררו בשנת 2009 תמורת שחרורו של חייל בריטי חטוף. לאחר שחרורו עברו חזאלי והנהגת AAH לאיראן, שם תיאמו תקיפות נגד כוחות אמריקאים, אישים בממשל העיראקי ותומכי צדר.25 בשנת 2011 הם שבו לבגדד בטקס חגיגי. חזאלי הוא המנהיג שאיים לאחרונה על ישראל מעבר לגבול לבנון.

בדומה לחיזבאללה ולקבוצות שיעיות מזוינות אחרות, ארגון AAH יצר מבנים פוליטיים משמעותיים והפך להיות מעורב ביותר בתהליכים פוליטיים. הוא פתח סניפים פוליטיים, הנהיג תוכניות של שירותים חברתיים עבור אלמנות ויתומים, וכן רשת של בתי ספר דתיים.26 “לפני קצת יותר משבע שנים הם היו רק ישות פרוקסי איראנית ששימשה לתקיפת אמריקאים”, אמר שר עיראקי, “כעת הם זוכים ללגיטימיות פוליטית והזרועות שלהם מגיעות לכל קצות מערך הביטחון. חלקנו לא הבחנו בכך עד שנעשה מאוחר מדי”.27

באופן מעניין התרחב הארגון גם ללבנון, ככל הנראה בתמיכה איראנית. AAH הקים סניף סורי, במסווה של הגנה על המסגד השיעי המקודש סידה זינב בפרברי דמשק. אך בדומה לקבוצות שיעיות אחרות, הם גם מנסים להציג את עצמם כמגיני כלל הקהילות, ואף ייסדו יחידה סונית קטנה בשנת 2015.

הסיוע האיראני לישויות הפרוקסי הכלולות בהגדרה הרחבה של PMU עובר דרך משמרות המהפכה – כוח קודס, בהנהגתו של סולימאני. סולימאני מנהל מערכת יחסים קרובה עם מפקדי המיליציות ומבקר אותם בשדה הקרב. התנהלות זו מאפשרת לו פיקוח צמוד על המיליציות השיעיות. סולימאני עצמו מבקר בעיראק באופן קבוע ומפקח על פעולות המיליציות, ובכלל זה המערכות נגד דאע”ש. הקרבה לגבול האיראני מקלה על השליטה האיראנית הישירה ועל אספקת הסיוע וההדרכה. על מנת לגבור על מחסומי השפה האיראנים נעזרים בישויות פרוקסי שיעיות ערביות אחרות, ובייחוד בחיזבאללה. לוחמי חיזבאללה משמשים כמדריכים וכמתורגמנים.28

חרף הניסיון והיתרונות היחסיים שלהם, האיראניים נתקלים באתגרים בכל הקשור לישויות הפרוקסי הקשורות אליהם. קבוצות פרוקסי שיעיות יריבות מגיעות לעיתים לעימותים, וחלקן אף מוצאות את האינטרסים שלהן כמנוגדים לאלו של איראן. בנוסף, השימוש של איראן במיליציות עיראקיות יוצר התנגדות רחבה בעיראק, ואיראן – האויב המר של שנות השמונים – עדיין מצטיירת כגורם עוין בעיני חלק גדול מהציבור בעיראק.

מיליציות שיעיות במלחמה נגד דאע”ש

המיליציות השיעיות העיראקיות מילאו תפקיד חשוב במלחמה נגד דעא”ש וספגו אבדות רבות. כ-2,500 אנשי מליציה עיראקים-שיעים נהרגו בלחימה נגד דעא”ש. המעמד המשפטי של המיליציות העיראקיות נוצר כתוצאה מפלישת ארגון דעא”ש מסוריה ב-15.06.2014 וכתוצאה מפסק ההלכה המוסלמי – הכרזת הג’יהאד של אייתוללה סיסתאני. פסק הלכה זה קורא לשיעים-עיראקים צעירים להתחמש על מנת להגן על המדינה מפני ארגון דעא”ש. המבנה שנוצר כתוצאה מכך, ה-PMU, צמח בסופו של דבר לכדי ארגון בן 49 מיליציות ובהן כ-150,000 לוחמים.

סיסתאני אינו מעורב בניהול היומיומי של ה-PMU. ביום הפלישה הכריז שר הפנים על הקמת PMU. האדם המוביל את הגוף הזה הוא פאלח אלפיאד, אשר שימש גם כיועץ לביטחון לאומי לראש הממשלה לשעבר, ח’יידר אל-עבאדי.

בפועל, ההנהגה הראשית של PMU וגרעין המיליציות החזקות ביותר המרכיבות אותה תומכות באיראן לכל אורך הדרך. שש מתוך שבע המיליציות המקוריות (בדר, KH, חיזבאללה אל-נוג’בא, AAH, סייד אל-שוהאדא, כתאיב גו’נד אל-אמאם) קשורות באיראן, תומכות בגלוי בטהראן ומקבלות סיוע ישיר מה-IRGC. מפקד ה-PMU, באדר אמירי, וסגנו, מוהנדיס, שימשו כסוכנים פרו-איראניים והיו להם יחסים קרובים עם סולימאני וכוח קודס. ארגון PMU כפוף באופן רשמי למשרד הפנים העיראקי. משרד זה נשלט גם הוא בעבר על ידי ארגון בדר כחלק מהקואליציה השלטת.

אחד מכותבי מאמר זה ליווה גורמים מה-PMU במהלך המערכות בבאיג’י, רמאדי ואנבאר במסגרת הלחימה בדאע”ש בשנת 2015. היה ברור כי התיאום בין המיליציות השיעיות והגורמים הנוספים בכוחות המזוינים העיראקיים המעורבים בלחימה – הצבא, יחידת העילית (הידועה גם בשם דיוויזיית הזהב) והמשטרה הפדראלית (הכוחות הצבאיים למחצה של משרד הפנים) – הושלם כש-PMU החל להשתתף בתדריכים, וכשבכירים ב-PMU החלו לתדרך קצינים בכירים בצבא העיראקי. כותב המאמר היה אף עד לתדרוך שניתן מפי סגן מפקד PMU, מוהנדיס, בבאיג’י, בחודש יוני 2015.

מוהנדיס פנה למפקדים בכירים ב-PMU ובצבא העיראקי. לבוש בבגדים אזרחיים, מוהנדיס היה הדובר היחיד בפגישה, ונראה היה שהוא אינו נתפס כשווה בין שווים אלא כמפקד הכללי. אחד מהקצינים הבכירים בצבא העיראקי כיום הסביר למחבר המאמר, לאחר התדרוך, את הדינמיקה במערך. הגנרל ג’ומעא ענאד, המפקד המבצעי של הצבא, וראש המשטרה הפדראלית, שני הגופים אשר יחדיו מהווים את כוחות הביטחון העיראקיים (ISF) באזור סלאח א-דין, העיר כי “רוב הכוחות העוסקים בפינוי השטח [פינוי של לוחמי דעא”ש] הם כוחות PMU”. בכל הקשור בביצועים של PMU ציין ענאד שני תחומים: ההכשרה והחימוש המצוינים של לוחמי PMU והמוטיבציה הגבוהה שלהם. בכל הקשור להכשרה ולחימוש אמר ענאד: “התמיכה האמריקאית כרגע איננה מספיקה. לארצות הברית יש כוחות רבים, אך הם מבצעים רק ארבע או חמש פשיטות ביום. האיראנים, לעומת זאת, מספקים ל-PMU תמיכה בלתי מוגבלת, נשק, תחמושת, יועצים. כעת אנו יכולים לראות את התוצאות”.

מוהנדיס עצמו, בשיחה עם מחבר המאמר באותה הזדמנות, אישר כי “ה-PMU נשען על הסיוע והיכולת של הרפובליקה האסלאמית של איראן”.

הביצועים הצבאיים של המיליציות בלחימה נגד דעא”ש נחשבים ליעילים למדי. המיליציות השתתפו במערכות מפתח במלחמה, ובכלל זה המערכה באנבאר, שחרור באיג’י, הכיבוש מחדש של תיכרית, המערכה ברמאדי ושחרור מוצול (שם הם שימשו כאגף השמאלי של הכוחות הנלחמים במדינה האסלאמית, ושהו במרחק 20 קילומטרים מהעיר הסונית הגדולה במטרה לצמצם את הסיכוי למתחים על בסיס דתי בעיר עצמה).

עם סיום המאבק בדעא”ש שולב ארגון PMU באופן רשמי בכוחות המזוינים העיראקיים. אולם, מיליציות PMU אחדות ממשיכות לפעול כשחקן פוליטי ומנסות להשיג יתרון פוליטי על בסיס המוניטין המצוין שקנו להן במהלך הלחימה נגד דעא”ש. רשימת “פתח” של המיליציות השתתפה בבחירות הכלליות ב-12 במאי, וזכתה במקום השני. היא עתידה להיות חלק חשוב בקואליציה העיראקית המתהווה בראשות ראש הממשלה עאדל עבד אל-האדי.

בד בבד עם ההתקדמות הפוליטית שלהן ושילובן בכוחות המזוינים, המיליציות השיעיות ממשיכות לפעול ככוח מזוין עצמאי, ככל הנראה בהנחיית איראן. לפיכך, על פי רויטרס, הן קיבלו טילים בליסטיים מה-IRGC, היכולים לשמש בעימות עתידי עם ישראל (ולאפשר לאיראנים להכחיש את אחריותם, בדומה להתנהלותם עם חיזבאללה בלבנון והחות’ים בתימן). הן אף פועלות תחת שליטה ישירה של ה-IRGC, ואינן מחויבות לשרשרת הפיקוד העיראקית הרשמית באזור גבול אל-קאים/אל-בוכמאל שבין עיראק לסוריה, כמו גם באזור מיאדין ממערב לאל-בוכמאל.

בשיחה שנערכה בחודש יוני 2015 בבגדד תיאר קצין בדר באוזני מחבר המאמר את התפקיד העתידי של PMU כתפקיד מקביל לתפקיד של IRGC באיראן – הכוחות המזוינים מטעם המדינה ממשיכים להתקיים, אולם מבנה מקביל של כוח מזוין נשמר גם הוא על מנת להגן על המהפכה. נראה כי זהו תיאור מדויק של הכיוון העתידי בכל הקשור למיליציות השיעיות בעיראק.

תפקיד המיליציות השיעיות העיראקיות במלחמת האזרחים בסוריה

המיליציות השיעיות העיראקיות, ובכללן גורמים הנתמכים ישירות בידי איראן, מילאו תפקיד חשוב בהגנה על השלטון הסורי ובהבסת דעא”ש בעיראק. תרומתן הייתה גדולה הרבה יותר בעיראק, ושיקפה את הנאמנות העיקרית שלהן לעיראק. נאמנות זו באה לידי ביטוי גם באבדות הרבות של המיליציות בלחימה במדינה האסלאמית, שם מספר הלוחמים שנהרגו היה גדול בהרבה ממספר הקורבנות של המיליציות במסגרת מלחמת האזרחים בסוריה. גם במהלך מלחמת האזרחים לחמו המיליציות בין היתר בכוחות דעא”ש. עם זאת, בשני המקרים מילאו המיליציות תפקיד חשוב בחזית הקרבות. בעיראק, חלקן בלחימה בדעא”ש היווה חלק חשוב מהלגיטימציה הציבורית הגוברת שניתנה להן והובילה הן להצלחה פוליטית והן לגיבוש תפקידן הצבאי כחלק מכוחות הביטחון של עיראק.

כאשר ההתקוממויות בסוריה החלו לקבל אופי צבאי מובהק, לקראת סוף שנת 2011, ניצב משטר אסד בפני דילמה. באופן רשמי עמד לרשות המשטר כוח מזוין עצום – 220,000 חיילים סדירים ו-280,000 חיילי מילואים, אך למעשה לא יכול היה המשטר לנצל את מרבית הכוח משום שהוא כלל ערבים סונים מגויסים – אותו פלח אוכלוסייה שממנו הגיעו המורדים.

המשטר בחר להתמודד עם הבעיה הזו בשני אופנים. ראשית, משלהי 2011, ובאופן שיטתי יותר מקיץ 2012, החל המשטר לסגת מאזורים שלא נחשבו לחיוניים מבחינת יכולת ההישרדות שלו. שנית, מתחילת שנת 2012 החל המשטר ליהנות מפריסת ישויות פרוקסי איראניות על אדמת סוריה, כחלק מתהליך שתואם על ידי כוח קודס של IRGC. בהקשר זה מילאו המיליציות השיעיות העיראקיות תפקיד חשוב.

המיליציות השיעיות העיראקיות, ובכללן כתא’יב חיזבאללה, עצאיב אל-חאק והבריגדות של אימאם עלי החלו, בתחילת 2012, להעביר לוחמים לסוריה תחת פיקוח איראני. מיליציות נוספות שהיו מעורבות בסוריה כללו את חיזבאללה אל-נוג’בא ו-כתא’יב סייד אל-שוהאדא. לכאורה, המשימה שלהן הייתה להגן על מסגד סידה זינב Sxh בדמשק. כמו כן ייסדה IRGC מיליציה שיעית סורית – בריגדות אבו פאדי אל-עבאס, שלאחר מכן החלו בעצמן לגייס עיראקים שיעים, טרם התפצלו בשלב מאוחר יותר של המלחמה למבנים פרו-איראניים שונים. התהליך נעשה בפיקוח של אנשי כוח קודס של IRGC על אדמת סוריה.

מיליציות שיעיות עיראקיות שימשו בחזיתות שונות במלחמת האזרחים בסוריה ולא הוגבלו לאזור המזרחי הגובל באיראן (אזור שבכל מקרה היה חזית שולית במלחמה שבין המורדים למשטר, שרובה התרחשה במערב סוריה). ארגון כתא’יב חיזבאללה, למשל, טוען כי פרס 1,000 לוחמים בחלב, בשיא המצור על העיר בסוף שנת 2015.

המיליציות השיעיות העיראקיות השתתפו באופן בולט בעימותים היחידים בין הפרו-איראניים למשטר אסד במהלך המלחמה בסוריה. העימותים התרחשו במהלך חודש אוגוסט 2018, כשארגון חכתא’יב חיזבאללה, שלחם לצד הבריגדות האפגאניות “פאטמיון” הנתמכות בידי איראן, סילק את כוחות המשטר מאזור אל-בוכמאל אל קאים, והותיר את מעבר הגבול בין סוריה לעיראק באזור זה תחת שליטתן הבלעדית של IRGC והמיליציות.

אירוע זה הינו משמעותי משום ששליטה במעבר גבול זה היווה משימה חיונית עבור איראן כחלק ממאמציה לכונן מסדרון יבשתי תחת שליטתה מאיראן, דרך עיראק, לתוך סוריה ועד ללבנון, הים התיכון והגבול עם ישראל. הלחימה בחודש אוגוסט 2018 מבהירה את תפקידן של המיליציות השיעיות העיראקיות הפרו-איראניות המשמשות ככלי בידי האיראנים (תפקיד שלא ניתן לייחס לצבא הערבי הסורי של אסד). הלחימה הסתיימה עם יציאתם של כוחות המשטר הסורי מהאזור. המיליציות השיעיות ואנשי IRGC שולטים כעת גם בצד העיראקי וגם בצד הסורי של הגבול.

בחינת הנתונים הקיימים בדבר האבדות מצביעה על התפקיד הצנוע יחסית שמילאו המיליציות העיראקיות בכל הקשור למלחמה שבין המשטר והמורדים בסוריה. המיליציות השיעיות העיראקיות ספגו ככל הנראה 117 קורבנות בלבד בסוריה. מספר זה הינו נמוך משמעותית בהשוואה למספר האבדות בקרב חלקים אחרים של כוחות פרו-איראניים שיעים בסוריה – 2,100 איראנים, כ-2,000 אפגאנים מבריגדת פאטמיון (ששימשו לעיתים קרובות כבשר תותחים בגל הראשון של התקיפות נגד המורדים), ומעט פחות מ-2,000 אבדות בקרב ארגון חיזבאללה הלבנוני. עם זאת, יש לזכור כי למיליציות האיראניות יש מסורת של חשאיות בכל הנוגע לפרסום מספר האבדות שלהן, כך שההערכה המספרית ככל הנראה נמוכה ביחס למציאות.

בשונה מיסודות איראניים, לבנוניים, פקיסטניים ואפגאניים של המאמץ האיראני בסוריה, התגבורות העיראקיות לא אוחדו לכדי כוח אחד, אלא הופיעו במתכונת של קבוצות מיליציה שונות, כשכל אחת מן הקבוצות הייתה בעלת זהות ורקע משל עצמה. קיימת השערה כי מצב עניינים זה הוא המועדף בעיני ה-IRGC והמשטר האיראני, משום שהוא מונע את אפשרות קיומו של כוח אסלאמיסטי שיעי מאוחד שיוכל בעתיד להיפרד מאיראן ולהפוך לעצמאי.

גם בסוריה היו המיליציות השיעיות מעורבות מאוד במיזמים איראניים בלתי-אלימים אך משמעותיים שהתקיימו בעקבות המלחמה. ישנו מאמץ איראני לשנות את ההרכב הדמוגרפי בחלקים מסוימים מסוריה באמצעות העברה של משפחות שיעיות, בייחוד מדרום סוריה – שם ישנו רוב שיעי – לאזורים בעלי חשיבות אסטרטגית בסוריה. המשפחות נקלטות בבתים שבעבר היו מאוכלסים על ידי ערבים סונים שעזבו במהלך המלחמה. האזורים המדוברים כוללים חלקים מפרברי דמשק, אך גם אזורים אחרים המחברים בין דמשק לחוף העלאווי ולגבול עם לבנון.

נטען כי ארגון חיזבאללה אל-נוג’בא (HHN), כוח שיעי עיראקי המסייע לצבא בקרבת איראן, פיקח על תהליך זה. ארגון זה הקים גם את ‘הבריגדה לשחרור הגולן’ שנועדה לסייע לכוחות המזוינים הסורים במלחמה עתידית נגד ישראל.

משמעות עליית המיליציות השיעיות העיראקיות מבחינת ישראל

נראה כי מלחמה עתידית של ישראל בצפון לא תהיה דומה לעימותים הקודמים עם ישויות הפרוקסי של איראן. בעוד שמלחמת לבנון השנייה ב-2006 הייתה מוגבלת למדי, הן מבחינה גאוגרפית (הקרבות היבשתיים נערכו בתחומי דרום לבנון בלבד) והן מבחינה פוליטית (איראן, סוריה ולבנון לא השתתפו באופן רשמי בלחימה בין צה”ל לארגון חיזבאללה), סביר כי מלחמה עתידית בצפון תכסה שטח נרחב הרבה יותר ומספר רב יותר של משתתפים.

במקרה שתפרוץ מלחמה כזו צפוי כי טהרן תימנע שוב מהתערבות ישירה וגלויה בלחימה עם ישראל, אך העברת האחריות למיליציות ולישויות פרוקסי ושיפור היכולות הצבאיות של ישויות אלו הם אלמנטים חשובים בעמדה של טהראן כלפי ישראל.

שימור חופש הפעולה והתמרון עבור ישויות הפרוקסי האיראניות בעיראק, סוריה ולבנון משמעותי גם הוא בהקשר זה. הדוח שפורסם על ידי “רויטרס” בחודש אוגוסט 2018, העוסק בהעברת טילים בליסטיים, הינו משמעותי במיוחד גם הוא, מכיוון שהוא מוכיח כי המיליציות רוכשות יכולות משופרות בעודן משמרות את עצמאותן ואת חופש הפעולה שלהן.

באופן דומה, הדיווחים בעניין העימותים בין כוחות אסד והמיליציות השיעיות ומיליציות IRGC באזור אל-קאים/אל-בוכמאל, על גבול סוריה-עיראק, משמעותיים מאוד. כרגע, למיליציות ול-IRGC שליטה על מעבר הגבול ללא מעורבות של כוחות ממשלתיים עיראקיים או סוריים. מצב זה מפשט את העברת הלוחמים והאספקה לאזור לחימה עתידי משוער בין ישראל לאויביה הקשורים לאיראן במקרה של מלחמה ביניהם. הפצצת מחנה כתא’יב חיזבאללה באזור אל-חארה בקרבת הגבול, ב-18 ביוני 2018, מצביעה על הכרה בצורך בנקיטת פעולה מצד ישראל נגד המיליציות.

המלחמה הבאה בצפון עלולה להיות אירוע מאתגר ומפרך שבמהלכו יבואו לידי ביטוי היתרונות של ישראל בכל הקשור בעוצמת אש וכוח מספרי רק לאחר שמאמצי צה”ל יצליחו לחבל במערך הרקטות והכוחות היבשתיים של חיזבאללה. ישראל לעולם לא תצליח לחסל או לשבות את כלל לוחמי חיזבאללה, אך מתקפה עיקשת ומתוכננת כראוי עשויה לשכנע לוחמי חיזבאללה רבים כי מאמציהם לא ישאו פרי. אך כל עוד הם נהנים ממסדרון יבשתי בשליטת איראן שדרכו יכולים לעבור אלפי לוחמים מהמיליציות השיעיות, כושר הספיגה של לוחמי חיזבאללה יהיה גבוה למדי. קרוב לוודאי שהם ימשיכו להילחם כל עוד הם יאמינו שהעזרה בדרך אליהם.

מבחינת צה”ל, תרחיש שבו המיליציות השיעיות מתאחדות עם כוחות חיזבאללה יעצים בעיה אחרת. כוחות היבשה של ישראל, מבחינת חיילים קרביים, קטנים מספרית ממה שמקובל לחשוב, גם אם נחשב את חיילי המילואים. ישראל תזדקק למספר רב של לוחמים אם בכוונתה לכבוש את הטריטוריה שממנה משוגרות הרקטות של חיזבאללה במקום להסתמך על אש מרחוק כפי שנעשה במבצעים קודמים. הלחץ התובעני על כוחות היבשה עלול אף להתגבר במקרה שאנשי מיליציות שיעיות יצטרפו למאבק.

מובן שהמיליציות השיעיות מעולם לא נאלצו להילחם באויב דוגמת צה”ל בשדה הקרב. כל ניסיון להסתמך על תמרונים יבשתיים, כפי שנעשה על ידם בהצלחה בעיראק, יהפוך אותם למטרות קלות עבור הכוחות האוויריים וכוחות השריון של ישראל. הם ילחמו בצבא מתקדם וחזק ביותר המסוגל להכניע אותם במהירות עם עוצמת אש מסיבית. יהיה זה הלם עבור הכוחות שהיו מורגלים במתקפות טרור נגד כוחות הקואליציה, או בלחימה יבשתית נגד אספסוף הלוחמים של דעא”ש. עם זאת, אם המיליציות השיעיות ילמדו מחיזבאללה ויאמצו היערכות הגנתית ושימוש במנהרות כדי לארוב ללוחמי צה”ל המתקדמים לעברם, וייוותרו ברובם במסתורים תת-קרקעיים באזורים עירוניים, הם עלולים להפוך את האתגר הניצב בפני ישראל לקשה אף יותר. בכל הקשור לעליונות מודיעינית כמפתח ליכולת של ישראל להתמודד בהצלחה עם נכסי חיזבאללה, יש עדיין עבודה רבה שצריכה להיעשות כדי להיערך מבחינת איסוף וניתוח מודיעיני על מנת שיוכלו להיות יעילים מספיק נגד האיום הנוסף.

המיליציות השיעיות העיראקיות מהוות מרכיב יחיד, רב-גוני ומוכשר יותר ויותר מתוך כלל הנכסים הצבאיים והפארא-צבאיים הזמינים לאיראן. ההתקדמות הצבאית שלהן בחמש השנים האחרונות התרחשה במקביל לעליית כוחן הפוליטי.

לצד שימור משטר אסד, עליית המיליציות משקפת את ההישג הבולט של כוח קודס של IRGC ואת השיטות שלו באזור בשנים האחרונות. הנוכחות שלהן מעלה באופן משמעותי את הטווח הפוטנציאלי של ההתערבות האיראנית באזור, ועלולה להעצים באופן משמעותי את היכולות האיראניות במקרה של מלחמה עתידית סמוך לגבולה הצפוני של ישראל.

[1] Bill Roggio, “קייס חזאלי, המיליטנט העיראקי, הזהיר אותנו מפני איראן. אנו התעלמנו ממנו”, The Weekly Standard , 07.09.2018.

[2] John Irish, Ahmed Rasheed, “בלעדי: איראן מעבירה טילים לעיראק כאזהרה לאויביה,” רויטרס, 31.08.2018.

[3] בספרות קיימות הגדרות רבות למונח ‘לוחמת פרוקסי’, אך בעבודה זו משמשת ההגדרה הבאה: מערכת יחסים בין שתי ישויות, בין אם הן מדינות ובין אם ארגונים, שבמסגרתה השחקן החלש יותר (הפרוקסי) נלחם בסכסוך מזוין מקומי שעליו הפטרון רוצה להשפיע תוך צמצום המעורבות הישירה שלו. לשתי הישויות אויב משותף, ושתיהן רואות יתרונות בשותפות. הן מתאמות את פעולותיהן במהלך הסכסוך.

[4] Seth Frantzman, “מדריך הטרמפיסט למיליציות השולטות בחלק גדול מעיראק”, ג’רוזלם פוסט, 08.04.2017.

[5] אורי גולדברג, לחשוב שיעית (בן-שמן: ישראל, משרד הביטחון, 2012), עמ’ 11–12.

[6] איברהים אל-מאראשי, “עיראק: המצאתו מחדש של מוקתדא א-סדאר”, אל-ג’זירה, 09.03.2016.

http://www.aljazeera.com/…/iraq-reinvention-muqtada-al-sadr-160309061939234.html

[7] Margaret Coker, “שנוא על-ידי ארה”ב וקשור לאיראן, האם סדאר הוא פניה של הרפורמה בעיראק?”, ניו-יורק טיימס, 20.08.2018.

https://www.nytimes.com/…/iraq-election-sadr.html

[8] Martin Chulov, “מנהיגים שיעים בשתי מדינות במאבק שליטה על המדינה העיראקית”, The Guardian , 15.04.2016.

https://www.theguardian.com/…/Shi’ite-leaders-iraq-iran-ayatollah-ali-sistani

[9] Faleh Jabar, Renad Mansour, “כוחות הגיוס העממי ועתידה של עיראק”, Carnegie Middle East Center, 28.04.2017.

http://carnegie-mec.org/2017/04/28/popular-mobilization-forces-and-iraq-s-future-pub-68810

[10] hadi al-amiri, “פרויקט אנטי-קיצוניות“.

https://www.counterextremism.com/extremists/hadi-al-amiri%20

[11] Ranj Alaaldin, “מקורות ועליונות המיליציות השיעיות בעיראק”, מגמות עכשוויות באידיאולוגיה איסלאמית, The Hudson Institute, 01.11.2017.

[12] נתונים על כוח האדם והפריסה של המיליציות מתוך Garret Nada and Mattisan Rowan, “חלק 2: מיליציות פרו-איראניות בעיראק”, The Wilson Center, 27.04.2018.

[14] Ali Kurdistani, “מנהיג המיליציה הקורא תיגר על ארצות הברית וגאה בנאמנותו לאיראן”, Rudaw, 06.07.2016.

http://www.rudaw.net/…/iraq/07062016

[16] “חאטא’יב חיזבאללה”, מתוך מיפוי ארגוני מיליציה (אוניברסיטת סטנפורד).

[17] J. Matthew McInnis, “אסטרטגיית ההרתעה האיראנית והשימוש בפרוקסי”, America, Enterprise Institute,29.11.2016 .

https://www.foreign.senate.gov/…/doc/112916.pdf

[19] Martin Chulov, “בשליטת איראן, המיליציה הקטלנית מגייסת את אנשי עיראק למות בסוריה”, The Guardian , 12.03.2014.

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/mar/12/iraq-battle-dead-valley-peace-syria

[20] Lis Sly, “קבוצת המיליציה הנתמכות על-ידי איראן בעיראק מגדירה עצמה מחדש כשחקנית פוליטית”, וושינגטון-פוסט, 18.02.2013.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/…/b0154204-77bb-11e2-b102-948929030e64_story.htmlf

[22] Sam Wyer, “The Resurgence of Asa’ib Ahl Al-Haq”, Institute of the Study of War, p. 6.

http://understandingwar.org/…/ResurgenceofAAH.pdf;

[23] Chulov, “בשליטת איראן”, ISW, 9.

[24] Wyer, Resurgence””, ISW, 9.

[26] Sly, “קבוצות מיליטנטיות הנתמכות על-ידי איראן”, וושינגטון-פוסט.

[27] Martin Chulov, “בשליטת איראן, המיליציה הקטלנית מגייסת את אנשי עיראק למות בסוריה”, The Guardian, 12.03.2014.

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/mar/12/iraq-battle-dead-valley-peace-syria

[28] שם.

- בניית אתרים

- בניית אתרים