Since the war in Ukraine—and even more so after the direct confrontation with Israel—Iran has moved between two opposing trends: on the one hand, preserving its dependence on the anti-Western alliance with Russia; on the other, expanding cooperation with China under a strategy led by Khamenei. This paper examines Iran’s disappointment with Moscow as a driver of change in Tehran’s foreign policy and shows how it seeks to establish a degree of relative independence even vis-à-vis its allies in the East.

Introduction: From a Marriage of Convenience to a Disappointing Partnership

Tehran and Moscow have deepened cooperation in recent years, primarily against the backdrop of their international isolation and the severe sanctions imposed on them by the West. This partnership gained further momentum with the outbreak of the war in Ukraine, when Iran supplied Russia with advanced weapons systems such as Shahed-136, Shahed-131, and Shahed-129 UAVs, receiving in return diplomatic legitimacy and alternative trade channels.[1]

A prominent example of the closeness between the countrues was the visit to Moscow by Iranian Foreign Minister Abbas Araghchi immediately after Iran’s first round of nuclear negotiations with the United States in the spring of 2025.[2]

Over the past year, however, the Iranian leadership has become increasingly disappointed with Moscow’s conduct. Among the most salient issues are Russia’s inaction in the face of Israeli strikes in Iran and Syria; its lack of commitment to securing the future of the Assad regime; its disregard for Iranian interests in the agreement between the United States, Azerbaijan, and Armenia to establish the “Zangezur Corridor”; and Moscow’s de facto recognition of the United Arab Emirates’ sovereignty over three disputed islands in the Persian Gulf—a particularly sensitive matter for Tehran.

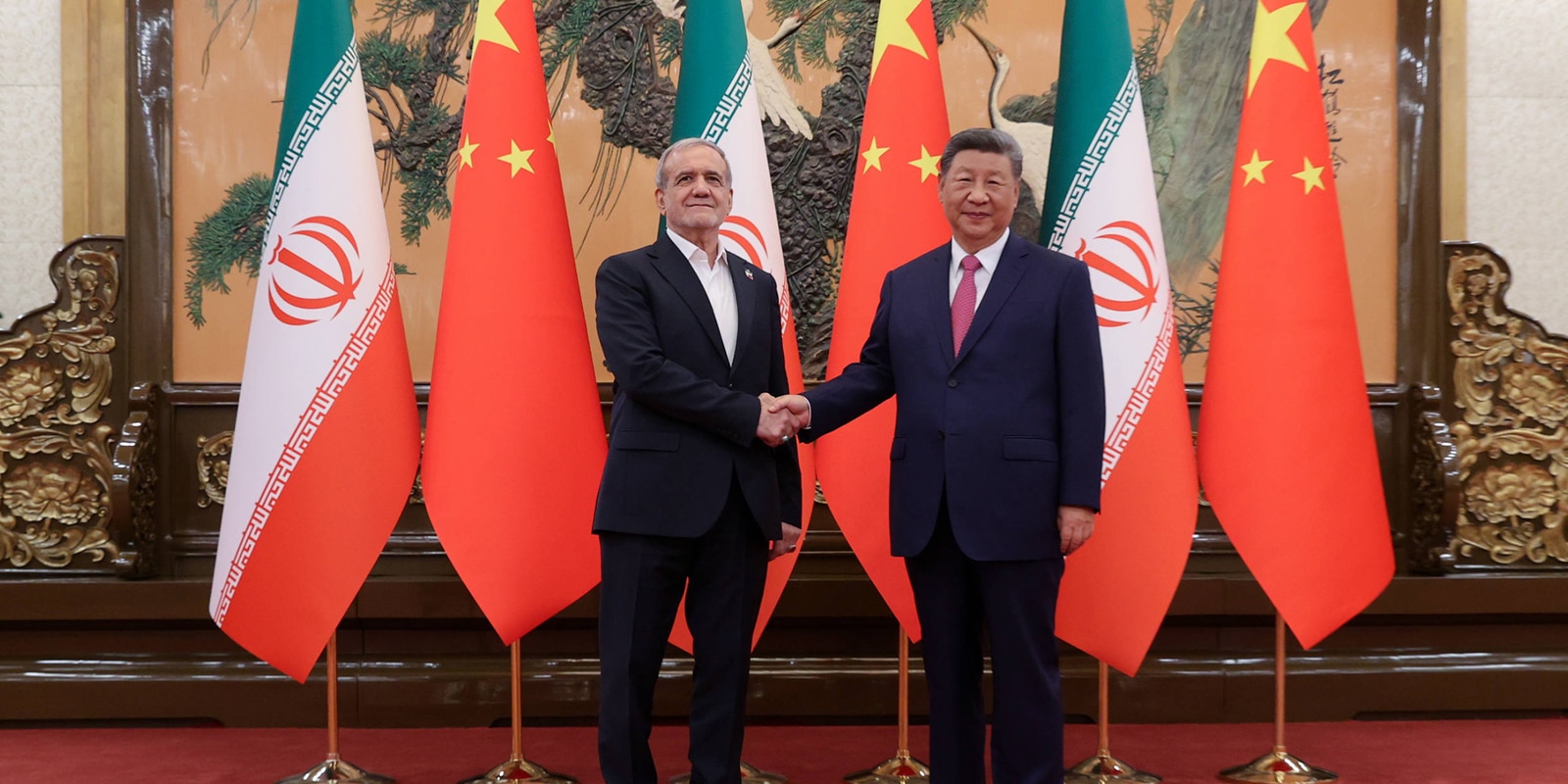

In response, immediately after the end of the war with Israel and the United States, Tehran began—with growing urgency—to shift the center of gravity of its relations with its strategic partners from Russia toward strengthening ties with China. For now, this trend is mainly reflected in rhetoric—such as that of the Supreme Leader, who has emphasized the importance of Sino-Iranian relations—but also in symbolic actions, such as President Masoud Pezeshkian’s successful visit to Beijing in early September 2025 and the expansion of economic and security agreements with China, following the visit of the late president Raisi to Beijing in February 2023.

This policy paper examines the principal indicators of Iranian frustration with Moscow’s policy and analyzes how this sense of disappointment affects Iran’s strategy. The evidence suggests that Tehran’s inclination to invest in relations with China is not merely a tactical expression of temporary disillusionment but part of a deeper geopolitical process reflecting Iran’s desire to establish itself as a central partner in the emerging Asian constellation—while reducing its dependence on Moscow and increasing its strategic flexibility vis-à-vis the West, Russia, and the region. This does not mean that Iran is abandoning its ties with Russia or halting its contacts with Moscow to procure advanced military equipment, including air-defense systems and fighter aircraft.

Operation Rising Lion — A Test of Confidence in Russia

Iran’s expectation of Russian assistance stemmed from the perception in Tehran that it had proven its loyalty to Moscow when the latter became mired in the Ukrainian quagmire. From the standpoint of Iran’s elite, Russia’s failure to respond was seen as a breach of strategic trust. Although Russia had made no commitment to help Iran defend itself against attacks on its territory—and Iran, for its part, had not sent forces to fight alongside Russia—Tehran’s expectations were for a more substantial and practical display of solidarity than the Kremlin in fact demonstrated.

Direct military exchanges between Iran and Israel began with Iran’s first missile and UAV attack on Israel in April 2024, followed by a second in October of that year. Israel responded with airstrikes on Iranian soil. In June 2025, Israel launched Operation Rising Lion, a large-scale surprise offensive targeting Iran’s nuclear and missile infrastructure, IRGC and army bases, regime symbols, senior military leadership, and nuclear scientists. The operation took place during ongoing negotiations between the United States and Iran on the nuclear issue and caught Tehran completely off guard in both its intensity and scope.

In the opening salvo alone, most of Iran’s military and security leadership was eliminated, including senior IRGC commanders and members of the General Staff, as well as nuclear scientists and other key figures. For twelve days, Israel and Iran engaged in intense exchanges of fire: Iran launched hundreds of ballistic missiles and UAVs toward Israel, while Israel systematically struck Iran’s nuclear and military infrastructure. The United States joined the Israeli effort, bombing three underground nuclear sites with bunker-penetrating munitions.

Although Tehran took care to project an image of victory and resilience, various voices within Iran expressed criticism and frustration. During the fighting, one question came up again and again in Iranian media: “Why didn’t Russia help Iran?” Many Iranians noted that Moscow, which had received significant Iranian support in its war in Ukraine, limited its response to statements in the media and took no tangible action to assist Tehran.

According to Western media reports, Iranian expectations were not confined to press statements but included explicit appeals. Reuters revealed, citing an anonymous source, that Iranian Foreign Minister Abbas Araghchi had flown to Russia at the height of the war with Israel and personally delivered to President Putin a letter from Iran’s Supreme Leader, Ali Khamenei, requesting assistance.[3] It is quite possible that Araghchi’s visit was intended to persuade Moscow to support Iran—at the very least through diplomatic efforts that might bring Israel and the United States to halt their offensive.

The public debate over Iran’s disappointment with Russia represented a rare point of consensus among Iran’s political factions, which are usually divided on matters of foreign policy. The Fararu news agency, associated with the moderate camp, published an article reviewing Russia’s passivity and reminding readers that Tehran had expected to receive advanced weapons systems from Moscow—SU-35 aircraft, S-300 air-defense systems, and Mi-28 attack helicopters—but these were not delivered. The article further argued that Moscow had benefited from the continuation of the Iran–Israel confrontation, benefiting from the rise in oil prices, and exploiting global distraction to intensify its attacks on Ukraine.[4]

Similarly, the conservative website Tabnak, which is affiliated with the IRGC, cited a report by the U.S. Naval Research Center stating that “Moscow’s approach was cautious and characterized by general condemnations, moderate language, and a lack of concrete or public action.”[5]

Alongside this media discourse, Iranian officials attempted to temper expectations. Yadollah Javani, the IRGC’s deputy commander for political affairs, argued that the alliance between Tehran and Moscow did not oblige direct military intervention, just as Tehran itself had not intervened directly in the war in Ukraine.[6] Iran’s ambassador to Moscow likewise stated that Tehran had not sought to purchase S-400 systems from Russia, despite reports to the contrary in the press.[7]

By contrast, Mohammad Hossein Safar-Harandi, a member of the Expediency Discernment Council, speculated that Israel had informed Moscow in advance of the attack on Tehran and questioned why the Russians had failed to warn Iran.[8] Another council member, Mohammad Sadr, went further, alleging that Moscow had shared intelligence with Israel—a claim that the Iranian Foreign Ministry swiftly denied, emphasizing that it did not represent Iran’s official position.[9] Sadr also noted that the advanced weapons systems promised to Tehran had not been delivered.

In conclusion, Russia’s lack of support for Iran during Operation Rising Lion reinforced the sense of a strategic breach of trust between the two countries—even if this was not expressed in official state positions—and underscored for Tehran the limits of its military reliance on Moscow. Another example of Iranian frustration with Russia’s failure to offer support during clashes with Israel appeared in an article published by the Iranian news site IR Diplomacy immediately after Israel’s October 2024 strike on Iran. The article noted that, following the attack, many countries condemned Israel’s actions—except for China and Russia. “Although China and Egypt issued partial condemnations of the attack,” the article observed, “Russia had yet to release any official statement by the time of reporting. This shows that Iran cannot rely on Moscow as a ‘strategic ally’ to defend its interests and national security.”[10]

The Fall of Assad — A Symbol of the Strains in Iran–Russia Relations

The revolutionary Iranian regime forged a close alliance with Syria as far back as the days of Hafez al-Assad, Bashar’s father. From the outbreak of the Syrian civil war in 2011, Iran was deeply involved in preserving Assad’s rule deploying both the IRGC and Hezbollah.[11] Alongside its military involvement, Iran invested in infrastructure, in the Shiite population, and in social-religious projects, seeking to establish a regional Shiite hegemony.[12] Over the years, Iran supported Assad by deploying combat forces[13] and even sending senior IRGC commanders to lead its operations in the country—some of whom were killed in Israeli strikes.

Russia likewise invested heavily in Assad’s regime, including through the establishment of major Russian bases in Syria—the air force base at Khmeimim and the naval base at Tartus—and by providing significant air support to the Syrian army and training its forces. Russia also invested in Syria’s economic development and reconstruction. In fact, Russian companies competed with Iranian firms for contracts.[14] Nevertheless, although tensions sometimes arose between Iran and Russia over Syria, it was clear that maintaining Assad’s rule was a strategic interest for both sides.

The fall of the Assad regime in 2024 dealt a severe strategic blow to Iran, particularly after the collapse of Hezbollah in Lebanon shortly beforehand, and constituted loss of a major ally and forward bastion against Israel. Two key pillars of Iran’s proxy network, built up over decades, had collapsed.

The shock in Tehran was absolute, and angry responses were directed toward Moscow. Iranian media outlets pointed to Russian passivity in Syria—its failure to bomb the al-Rastan Bridge[15] (a key crossing between the cities of Hama and Homs, whose destruction might have slowed the rebels), delays in striking rebel positions, and even indirect assistance to Israel by obstructing Iranian entrenchment in southern Syria and the Golan Heights.[16] Tabnak published a recording of a senior Iranian official in Syria, claiming that the Russians “bombed empty houses instead of rebel concentrations” and that this had contributed to Assad’s fall. The report appeared under the unusual headline: “Russian Betrayal in Syria.”[17]

The collapse of the Syrian regime undermined the core rationale of Iranian-Russian cooperation—the preservation of allied regimes in the region. From Iran’s perspective, Russia demonstrated that its commitment to maintaining the regional balance of power outweighs its loyalty to its partners. Admittedly, Russia’s military situation since the outbreak of the war in Ukraine limited its ability to provide significant assistance to Assad’s regime. Moreover, the limited capabilities of Assad’s forces and Hezbollah’s weakening in the wake of Israeli strikes and the assassination of its senior echelons further reduced their fighting capacity against the rebels. Nevertheless, Iranian rhetoric clearly conveyed a sense of abandonment, and even betrayal, by Moscow.

The Zangezur Corridor – A New Geopolitical Fault Line

The peace agreement between Azerbaijan and Armenia, brokered by the United States on August 8, 2025, has profoundly altered Iran’s geopolitical position. Under the agreement, Washington assumed responsibility for operating the Zangezur Corridor, a strategic land route connecting two parts of Azerbaijan separate by Armenian territory. The American presence near Iran’s northern border is viewed in Tehran as a direct constraint on its freedom of action, particularly with regard to its ally Armenia. Iranian officials also fear a potential military buildup by hostile actors—chief among them the United States, Israel, and Turkey—along its frontier.[18]

Institutionalizing the corridor could also undermine Iran’s long-standing ambition to become a central transportation hub within China’s Belt and Road Initiative. The resulting disruption of access to the Caucasus poses both security and economic challenges and tarnishes Tehran’s prestige in the eyes of Beijing.

Tehran regards the agreement as a serious threat to its interests, and conservative factions have called on Moscow to intervene and block what they describe as American infiltration of the region. Ali Akbar Velayati, senior adviser to Supreme Leader Khamenei, declared: “We will secure the South Caucasus ,with or without Moscow. And of course, we believe Moscow also opposes this corridor.” He added that just as Russia launched a war to prevent Ukraine from joining NATO, so too Iran “will not allow NATO to approach its borders.”[19]

Similarly, the hardline newspaper Kayhan, edited by Hossein Shariatmadari—one of Khamenei’s closest confidants—urged Moscow to act, warning that “if Moscow does not stand by Tehran today to block this project, it will tomorrow pay alone the heavy price of multi-front encirclement and strategic attrition.”[20] By contrast, Foreign Minister Araghchi emphasized that Iran “will be particularly sensitive to any plan that limits its transport access or undermines its vital interests,” adding that discussions on the matter have been held with Russia and Armenia,[21] Iran’s principal allies in the Caucasus region.

Russia’s Recognition of the UAE’s Sovereignty Persian Gulf Islands

In a joint statement issued at the conclusion of the July 2023 meeting between the foreign ministers of Russia and the Gulf states, the parties expressed their support for “efforts to achieve a peaceful resolution of the dispute between Iran and the United Arab Emirates over three islands in the Persian Gulf—Greater Tunb, Lesser Tunb, and Abu Musa—through bilateral negotiations or by referring the matter to the International Court of Justice, in accordance with international law and the UN Charter.” The wording of the statement effectively reflected support for the UAE’s position, which asserts sovereignty over the islands, and implicitly cast doubt on Iran’s ownership of them—a highly sensitive issue for Tehran, which regards the three islands as an inseparable part of its sovereign territory since the days of the Shah.[22]

Iran’s reaction to Russia’s statement on the three islands was sharp and unusually harsh, becoming a central issue in public and political discourse in Tehran. The Iranian Foreign Ministry summoned the Russian ambassador for a clarification and delivered an official protest over Moscow’s repetition of the Arab states’ position against Iran’s territorial integrity. In its statement, the ministry declared that the three islands “were and will remain an inseparable part of the territory of the Islamic Republic” and that any attempt to undermine this sovereignty “contradicts the principles of friendship and mutual respect between the two nations.”[23]

Within Iran, public criticism of Moscow was likewise unprecedented. Ali Akbar Velayati, Khamenei’s senior adviser on foreign affairs, described Russia’s stance as “regrettable.” Velyati stated that, “The adoption of certain positions by the Russian Foreign Ministry is unfortunate. However, given the complex circumstances, certain political pressures on Russia are causing it to damage its reputation in pursuit of low-value and unattainable gains.”[24]

Similarly, Heshmatollah Falahatpisheh, former chair of the Majlis National Security and Foreign Policy Committee, responded: “Within just one week, Iran Air was sanctioned because of Russia; a statement on the Iranian islands was issued following Lavrov’s joint meeting with the GCC Council; and Putin took Zangezur hostage. Russia is not a friend in hard times but the main cause of hardship for Iranians.”[25]

The Iranian daily Jomhouri-e Eslami described Russia’s statement as a “political betrayal,” noting that it had been issued “only two weeks after Putin shook the Iranian president’s hand in the Kremlin”—a gesture that, it said, made the move “both surprising and troubling.”[26] The paper continued: “The fact that Russia, despite these protests and the existence of undisputed documents and evidence, still commits such a betrayal of Iran’s territorial integrity says nothing other than hostility toward Iran and a lack of trust. Chinese and Russian officials have tried to downplay the incident by offering unfounded explanations whenever Iran protested, but they have never attempted to atone for their betrayal.”[27]

Looking to the Future – China as an Alternative Strategic Anchor

Iran’s attitude toward Russia over the past year can be summed up in the phrase: “The higher the expectations, the greater the disappointment.” While senior Iranian officials have refrained from openly criticizing Moscow, state-controlled media in Tehran have voiced growing frustration—particularly in light of the lofty hopes pinned on Russia as a strategic ally in the fields of armaments, diplomatic backing, and joint opposition to the United States and Israel. Still, Iran avoids direct confrontation or any suspension of cooperation, continuing to cultivate ties with Russia in the security and energy domains. The real alternative to its close partnership with Moscow—capitulating to Western pressure and halting uranium enrichment in exchange for sanctions relief—remains unacceptable to Iran’s leadership. China may offer limited military, economic, and diplomatic support, but it cannot fully replace Russia so long as Iran remains under heavy sanctions. Consequently, despite its disappointment, Tehran is likely to preserve its close ties with Moscow, hoping for a more stable and mutualy beneficial relationship in the future.

In August–September 2025, during President Pezeshkian’s visit to Beijing, Supreme Leader Khamenei posted on his X account in both Persian and Chinese that “Iran and China, with their ancient cultural histories and located at the two edges of Asia, have the power to bring about change in the regional and global order. The implementation of every aspect of the strategic agreement signed between them paves the way for this.”[28] Pezeshkian added that “the Supreme Leader has emphasized developing relations with China and instructed us to pursue the matter. I hope that with the establishment of a joint working framework, the agreements between our two countries will soon be implemented.”[29]

After the president’s return from China, Khamenei met with Pezeshkian and his cabinet and reviewed the achievements of the trip, saying: “The president’s recent visit to China was highly successful. It represents not yet a reality, but a potential for fertile ground for significant events vital to our nation, both economically and politically… it achieved results, and we must continue to build on them, God willing.”[30]

Khamenei’s senior advisers have echoed this growing trend of moving closer to Beijing. Ali Akbar Velayati, the Supreme Leader’s senior adviser, wrote: “As time passes, the closeness between Iran and China deepens, and I believe this solidarity will grow stronger in the near future.”[31] His comments reflect the prevailing view within the Iranian establishment that the partnership with China serves as a stable, long-term strategic anchor.

Along the same lines, President Pezeshkian declared after his meeting with China’s president that “China can rely on Iran as a strong ally,” emphasizing the readiness of both nations to expand cooperation in all fields through the full implementation of their 25-year strategic agreement.[32]

Foreign Ministry spokesman Esmaeil Baghaei added that “the 25-year agreement with China is already in the implementation stage,” asserting that “Iran is determined to advance its interests in the face of European demands.”[33] He noted that numerous bilateral accords had been signed in trade, economy, energy, agriculture, and tourism, and that “Iran–China relations rest on mutual trust and shared understanding, grounded in centuries-old historical and cultural ties. On this basis, the foundations and principles of our bilateral relationship are very strong, and both nations are determined to continue developing these ties in pursuit of mutual interests.”[34]

Shortly after Pezeshkian’s return from Beijing, Mohammad Reza Manafi, an Iranian expert on China and South Asia, published a commentary that captures Iran’s worldview regarding the 25-year strategic partnership with China. Manafi described the agreement as a pillar for realizing Iran’s economic, technological, and defense potential, and as the basis for shaping a long-term partnership with a global power independent of Western influence. According to him, China offers the world an “open table” for cooperation founded on the principle of mutual benefit and shared success—an approach Manafi states is fundamentally at odds with the U.S. unilateral doctrine of “America First.” Unlike Washington, Manafi stressed, Beijing views the prosperity of other nations as mutually beneficial and actively implements this cooperative model in Africa, Latin America, the Middle East, the Arab world, and even Europe.[35]

Manafi further argued that given Iran’s acute security sensitivities and the possibility of another Israeli military strike, Tehran should explore incorporating advanced Chinese defense procurements and systems into the strategic partnership. This, he wrote, could meet Iran’s defense needs and strengthen its deterrence capabilities.[36]

He also pointed out that China has proven expertise in tackling structural challenges similar to those Iran faces—water shortages, air pollution, energy crises, and desertification—and has implemented large-scale solutions in renewable energy, green technologies, and advanced transportation. China, he added, is willing to share its experience and technology with Iran, provided mutual agreements are finalized. Manafi also noted that Beijing’s close relations with European countries could help block the activation of the “snapback mechanism” against Iran, as China itself has a vested interest in preserving Tehran’s stability.[37]

In practice, on August 28, 2025, the snapback mechanism was triggered, yet China and Russia have chosen to ignore it and continue their military and economic cooperation with Iran. China remains the leading importer of Iranian oil, whose exports have risen in recent months as a result—despite Western sanctions—and Russia has once again committed to constructing four nuclear power plants in Iran. Moreover, both China and Russia’s disregard for renewed sanctions is reflected in their continued discussions over the supply of aircraft and advanced air-defense systems to Tehran.

Conclusion

The warming of Iran’s relations with China is unfolding against the backdrop of growing disappointment with Moscow. Although there is no evidence that Tehran is abandoning Russia in favor of China, it appears intent on expanding its circle of partners—particularly in the field of advanced weaponry, where the Russians have failed to meet its expectations.

In Tehran, there is recognition that its air and defense systems failed during the war with Israel, and the leadership now seeks to procure new systems such as the S-400 and SU-35 aircraft from Russia, or their Chinese equivalents. The contest over the supply of these systems may serve as a gauge of the depth of Tehran’s relations with each of the two powers. It is entirely possible that the rapprochement with China is intended to spur Moscow to stand more firmly at Tehran’s side.

Amid the erosion of trust toward Moscow, Tehran seeks to reshape its image on the international stage—not merely as a third fiddle in the anti-Western camp led by Russia and China, but as an independent regional power aiming to develop separate partnerships with China, India, and the countries of Southeast Asia. Should this trend deepen, it could reinforce Iran’s tendency to rely on a Chinese economic and technological infrastructure at the expense of its military dependence on Moscow.

Still, even in the case of China, much remains unclear: Although the two countries have signed a long-term cooperation agreement, most of its clauses and the extent of their implementation have not been made public. In broader perspective, the alliance between Iran, Russia, and China rests primarily on strategic convenience and their shared opposition to U.S. policy—factors that also underlie its inherent weaknesses, as illustrated by the state of the Tehran–Moscow relationship. In any event, China remains only a partial substitute for Russia from Iran’s perspective, and Tehran will therefore continue striving to extract maximum benefit from its ties with Moscow despite its frustration and disappointment.

* The information on which this paper is based is current as of November 5, 2025. Sincere appreciation is extended to Daniel Hirschfeld for his assistance in the extensive research for this paper.

[1] Yaakov Lappin, “The Tehran–Moscow–Beijing Triangle,” The Jerusalem Institute for Strategy & Security, November 6, 2025. https://jiss.org.il/en/lappinthe-tehran-moscow-beijing-triangle/

[2] “Meeting with Foreign Minister of Iran Abbas Araghchi”, The Kremlin, April 17, 2025. http://www.en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/76710

[3] “Iran Makes Direct Plea to Putin After US, Israel Strikes”, “Newsweek” News Site, June 23, 2025. https://www.newsweek.com/iran-makes-direct-plea-putin-after-us-israel-strikes-2089243

[4] “What Lies Behind Russia’s Passivity in the Iran–Israel War?” (in Persian), Fararu News Agency, June 26, 2025, https://fararu.com/fa/news/878775.

[5] “The Only Russian Who Seriously Supported Iran in the Iran–Israel War—and Then Retracted His Words” (in Persian), Tabnak News Site, July 14, 2025, https://www.tabnak.ir/fa/news/1317136.

[6] “Why Didn’t Russia and China Help Iran in the ‘Imposed Israeli War’? / The IRGC Deputy for Political Affairs Responds” (in Persian), Donya-ye-Eqtesad News Site, August 3, 2025, https://donya-e-eqtesad.com/%D8%A8%D8%AE%D8%B4-%D9%81%DB%8C%D8%AF-%D8%B3%DB%8C%D8%A7%D8%B3%DB%8C-81/4201618.

[7] “Iran’s and Russia’s Positions Have Grown Much Closer on the International Stage” (in Persian), Kayhan Newspaper, September 13, 2025, https://kayhan.ir/fa/news/318132.

[8] “Israel Contacted Russia Before Striking Iran” (in Persian), Tabnak News Site, August 5, 2025, https://www.tabnak.ir/fa/news/1321246.

[9] “Bakaei: Mohammad Sadr’s Claims Are Personal and Incorrect” (in Persian), Mashregh News Site, August 25, 2025, https://www.mashreghnews.ir/news/1743539

[10] “Moscow’s Meaningful Silence on Israel’s Aggression Against Iran: From the S-300 and Zangezur to the Three Islands, the Nuclear Agreement, and the War in Ukraine; When Russia’s Betrayals Know No End” (in Persian), IRDiplomacy News Site, October 29, 2025, http://www.irdiplomacy.ir/fa/news/2029048

[11] “Syria: Iran and Hezbollah’s Savior and Achilles’ Heel”, CSIS, October 10, 2024. https://www.csis.org/analysis/syria-iran-and-hezbollahs-savior-and-achilles-heel

[12] “Here to Stay: Iran’s Involvement in Syria, 2011–2021,” Institute for National Security Studies (INSS), November 2021.

[13] “Iran to send 4,000 troops to aid President Assad forces in Syria”, “Independent” News Site, June 16, 2025.

[14] “The Treacherous Triangle of Syria, Iran, and Russia”, Washington Institute, Spring 2023.

https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/sites/default/files/pdf/Borshchevskaya202303063-MEQ.pdf

[15] “Signs of Russian Betrayal Aimed at Toppling Bashar al-Assad?” (in Persian), Tabnak News Site, December 11, 2024, https://www.tabnak.ir/fa/news/1277344

[16] “The Russian Presence in Southern Syrian Provinces Before Assad’s Fall Served an Israeli Interest: Russian Patrols Were Supposed to Prevent Pro-Iranian Groups from Entrenching Themselves in Southern Syria” (in Persian), Entekhab News Site, August 12, 2025, https://www.entekhab.ir/fa/news/879798

[17] “Recording of a Revolutionary Guards General on Bashar al-Assad’s Fall: From Russian Betrayal to the Assassination of Iranian Commanders” (in Persian), Tabnak News Site, January 7, 2025, https://www.tabnak.ir/fa/news/1282181

[18] “Iran and Russia are the Main Losers of the Peace Treaty between Azerbaijan and Armenia”, The Jerusalem Institute for Strategy & Security, August 24, 2025.

https://jiss.org.il/en/grinberg-iran-and-russia-are-the-main-losers-of-the-peace-treaty-between-azerbaijan-and-armenia/

[19] “Exclusive | Velayati: Iran Will Block the American Corridor in the Caucasus—with or without Russia / The Dream of Hezbollah’s Disarmament Will Not Come True” (in Persian), Tasnim News Agency, August 9, 2025, https://www.tasnimnews.com/fa/news/1404/05/18/3372497

[20] “What Negligence Led to Leasing ‘Zangezur’ to America?” (in Persian), Kayhan Newspaper, August 9, 2025, https://kayhan.ir/fa/news/316185.

[21] “Araghchi: Iran Pays Special Attention to Maintaining the Region’s Geopolitical Stability and Its National Interests” (in Persian), Tasnim News Agency, August 14, 2025, https://www.tasnimnews.com/fa/news/1404/05/23/3375917.

[22] “Joint Statement of the 6th Russia – GCC Joint Ministerial Meeting for Strategic Dialogue”, Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, July 10, 2025.

https://mid.ru/en/foreign_policy/rso/1896567

[23] “Russia Again Supports Arab States’ Claim Against Iran’s Territorial Integrity / Iran Restricts Itself to a Strong Verbal Protest Only” (in Persian), Asr Iran News Site, December 21, 2023, https://www.asriran.com/fa/news/928224.

[24] “Leader’s Adviser Openly Criticizes Russia / Russia’s Position on the Iranian Islands Is Regrettable” (in Persian), Asr Iran News Site, December 22, 2023, https://www.asriran.com/fa/news/928378.

[25]“Three New Russian Measures Against Iran, According to Falahatpisheh / The Russians Are the Main Source of Iran’s Difficulties” (in Persian), Asr Iran News Site, September 11, 2024, https://www.asriran.com/fa/news/996690.

[26] “Jomhouri Eslami Newspaper: Russia’s Betrayal Only Two Weeks After Putin Shook Hands with Iran’s President in the Kremlin” (in Persian), Asr Iran News Site, December 22, 2023, https://www.asriran.com/fa/news/928494.

[27] Ibid

[28] “The Supreme Leader Emphasizes Implementation of the Iran–China Strategic Agreement” (in Persian), Official Website of the Supreme Leader of Iran, August 31, 2025, https://farsi.khamenei.ir/news-content?id=61061.

[29] “Pezeshkian: The Leader of the Revolution Instructed Us to Continue Developing Relations with China” (in Persian), Tasnim News Agency, September 3, 2025, https://www.tasnimnews.com/fa/news/1404/06/12/3390987.

[30] “The President and Cabinet Members Meet with the Leader of the Revolution” (in Persian), Official Website of the Supreme Leader of Iran, September 7, 2025, https://farsi.khamenei.ir/news-content?id=61219.

[31] “The Importance of Iran–China Relations from a Regional Perspective” (in Persian), Tasnim News Agency, April 9, 2025, https://www.tasnimnews.com/fa/news/1404/01/20/3288483.

[32] “Pezeshkian: China Can Rely on Iran as a Strong Ally” (in Persian), Tasnim News Agency, September 2, 2025, https://www.tasnimnews.com/fa/news/1404/06/11/3390796.

[33] “Bakaei: The 25-Year Agreement with China Is in the Implementation Phase / Iran Is Serious about Advancing Its Interests vis-à-vis European Demands” (in Persian), Tasnim News Agency, September 1, 2025, https://www.tasnimnews.com/fa/news/1404/06/10/3389624.

[34] Ibid

[35] “The 25-Year Agreement: The Axis for Activating Capabilities” (in Persian), Tasnim News Agency, September 9, 2025, https://www.tasnimnews.com/fa/news/1404/06/18/3395633.

[36] Ibid

[37] Ibid

JISS Policy Papers are published through the generosity of the Greg Rosshandler Family.

Disarm Hamas or Face a Partitioned Gaza