The Kingdom of Qatar, a repressive, discriminatory regime at home, promotes a cynical media policy abroad that lavishes support on a conservative, religiously-oriented Al Jazeera Arabic while simultaneously supporting a “progressive” media site AJ+ in English and other languages. Its themes contradict the regime’s nature and harsh domestic policies, as the recent criticism of Qatar came to bear during the recent soccer World Cup held there. Virulent hatred for Israel and a solid anti-US bias are the only common denominator between the two media sites.

Were a media consumer of AJ+ to reflect on who funded this “progressive” media site devoted to social justice, the plight of minorities, the fight against energy companies in particular and capitalism more generally, all with a heavy dose of anti-Americanism, they could easily conclude that in the notable absence of any advertising revenue, the source of the funding is a wealthy foundation supported by wealth progressives, or by thousands of less well-endowed similarly inclined individuals. They could hardly guess that the creator, sponsor, and sole provider was the Kingdom of Qatar, an oil-rich state run by an autocrat and his family who suppresses any attempt at democracy, denies citizenship to many inhabitants indigenous to the area (and all the more so to immigrant workers who form the overwhelming percentage of the population), and suppresses women and workers’ rights – issues that AJ+ champions!

Expressing moral opprobrium toward states that deserve it is hardly in vogue today, least of all regarding the energy-rich and opulently wealthy Kingdom of Qatar. So successful has the Kingdom been in concealing what it is and the harm it does that it has managed to host a large US air force base despite its warm relationship with Iran – relations that undermine US sanctions against Iran. More startlingly, in its recent accord with Lebanon designating the territorial waters between the two states, the government of Israel announced that it would permit a Qatar energy company to search for and exploit gas in the area despite Qatar’s relentless campaign encouraging Palestinian terrorism. That campaign, especially targeting Hamas, is done through its Arabic Al Jazeera media site – a popular site among Palestinians. Qatar also hosts Hamas leaders royally, the most prominent of whom was former Hamas leader Khaled Mashaal.

This project’s overall goal is to analyze how Qatar has managed to mute, though hardly silence, the gap between what the Kingdom is and what it does and the image of Qatar as a benign state that promotes stability and peace at home and abroad. That will be seen by analyzing principally its media policy, to which it expends much of the Kingdom’s vast resources.

We begin with an analysis of what Qatar is, then evaluate the differences between the two media sites it funds: the far more popular Al Jazeeramedia site in Arabic and AJ+ aimed principally at non-Arabic speaking audiences, and compare both with BBC Arabic’s coverage and that of CNN and Fox News, on the international level. The last part will conclude with a comparison between the nature of the Qatari state and the media it generates and compare the heart of the coverage of Qatari media sites relative to others. It will reveal the cynic duplicity of the Kingdom that goes well beyond the gap between the idealistic and apologetic rhetoric of states and their actual pursuit of national interests.

Qatar: A repressive regime that preaches the opposite of what it practices

Were it not for its vast wealth, attributable to its abundance of gas and oil reserves (principally the latter) and its geostrategic setting, the tiny Kingdom of Qatar would probably generate news similar to Iceland – heavy on tourist and lifestyle news and little of broader political and geostrategic concerns. However, this is hardly the case.

Qatar, significantly smaller than Connecticut geographically (4,468 sq.mi. to 5,543.3 sq.mi.) and demographically (2.8 million compared with 3.6 million, respectively), is the sixth-highest gas producer in the world. That explains why on a per capita basis, Qataris are some of the wealthiest citizens in the world, even when, erroneously, total gross domestic product is divided by the total population.

Qatar’s total population is irrelevant in assessing the true wealth of Qataris since only 18% (320,000) are citizens (according to unofficial sources, 12%), while 82% (or 88% according to foreign sources) are indigenous to the land. They have consistently been refused statehood, and foreigners who service the state and its citizens are not allowed to enjoy the vast citizenship privileges generated by its energy resources. If the Wikipedia entry for 2022 gives a GDP per capita figure of nearly $90,000 (one-third higher than in the US), the actual figure for Qatari citizens is at least five times that amount, or $450,000 – a level of wealth unparalleled in the world, with a vast but unknown percentage controlled by the small royal al-Thani family that rules Qatar.

Qatar’s wealth is also a significant security vulnerability, as reflected in Saddam Hussein’s occupation of energy-rich and neighboring Kuwait over three decades ago. Bordering the large and hostile Arab state Saudi Arabia explains the duplicity in Qatari foreign policy: its considerable efforts to ensure a US air force base on its soil, on the one hand, while maintaining a close if not an intimate relationship with the Iranian theocratic regime to balance against Saudi Arabia on the other. It also explains its sponsorship of Sunni fundamentalist groups, the Muslim Brotherhood, Hamas, and possibly the Islamic State in its backing of the Muslim fundamentalist-dominated government in Tripoli against the Tobruk alternative supported by Egypt and the United Arab Emirates. Both states broke ties with Qatar for its support of domestic Muslim Brotherhood terrorism in their respective states.

Qatari foreign policy is hardly benign.

Just as Qatar is synonymous with unprecedented wealth, it is also synonymous with despotism. The outline about Qatar on democracy and human rights on the Freedom House media site – devoted to plotting and measuring democracy and the maintenance of human rights among the world’s nations – summarizes it best:

Qatar’s hereditary emir holds all executive and legislative authority, and ultimately controls the judiciary as well. Political parties are not permitted, and the only elections are for an advisory municipal council. While Qatari citizens are among the wealthiest in the world, the vast majority of the population consists of noncitizens with no political rights, few civil liberties, and limited access to economic opportunity.[1]

It is hardly surprising then that Freedom House consistently gives the lowest score in its three-way typology of free, semi-free, and non-free states to seven countries, which Qatar shares with the likes of Iran, North Korea, and Syria.

Nor do recent developments suggest any change in the Kingdom. Though an election took place in October 2021 to decide membership in the Advisory Council (Majlis Al-Shura), the institution remained an advisory body to which the king nominated 15 seats. It was preceded by ratifying a law restricting the voter franchise to “native” Qataris whose families had settled in Qatar before 1930.

In almost every walk of life, Qatari rule violates fundamental human rights, especially of foreign workers who comprise the country’s vast majority of residents. A report in The Guardian in February 2022 estimated that more than 6,500 migrant workers died in the 10 years since Qatar won hosting rights to the 2022 World Cup. Three Norwegian journalists investigating migrant worker conditions in Qatar were arrested and briefly detained by the authorities in November. In its 2021 summary on Qatar, Human Rights Watch scored its leaders for not taking measures to protect workers preparing for the World Cup during the extreme heat wave in the Gulf States in the summer of 2021.[2][3] In response to a recent workers’ strike over not being paid, the Kingdom responded by expelling the workers from the country.[4]

The matter hardly ended there. To suppress would-be reformers, Jordanian-Palestinian communications executive Abdullah Ibhais, an advocate of these workers’ cause, was accused of leaking state secrets. Based on a signed confession Ibhais claimed he was forced to sign, he was sentenced to five years in prison, subsequently reduced to three. According to Human Rights Watch, the evidence on which the ruling was based was “vague, circumstantial, and in some cases contradictory.”[5]

Discrimination against people of color, which the Qatari-funded progressive media site AJ+ rightly condemns, is also rife in the Kingdom. E Tendayi Achiume, UN Special Rapporteur on contemporary forms of racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia, and related intolerance, visited Qatar in November 2019. Following the visit, the official highlighted discrimination, “stereotyping,” and “profiling” of migrant workers and the difficulties workers of color (the vast majority of the population) securing entrance to local shopping malls, practices that are widely prevalent in other Gulf States that rely on foreign workers. Achiume acknowledged the “significant reforms the government has embarked on that stand to make important contributions to combatting structural racial discrimination” but added that there was much room for improvement.[6] Ironically, the caste-laden Kingdom shares this characteristic with other Gulf States, significant sponsors of condemnations of Israel as a racist state.

Sanctioning the LGBT community and denying them equal rights is hardly unique to the Kingdom of Qatar. Such policies are common to the Gulf States and indeed to all the Arab-speaking states (known collectively as the Arab world), where the Sharia, which condemns homosexuality, is “the” basis of law-making. Qatar, however, is unique in sponsoring a “progressive” media site such as AJ+, whose foci stand in utter contrast to the practices of the state. During the recent World Cup, Qatar security personnel prevented LGBT flags from being displayed.[7]

The problem of women’s rights in Qatar is an issue both among the privileged Arab minority who have citizenship and among the disenfranchised non-Arab (primarily South Asian) majority. The difference lies in the magnitude and severity of the problem for foreign women. Among Qatari citizens, female inequality is reflected in inheritance, divorce, and child adoption matters. This inequality intersects with the issue of citizenship and the more onerous limitations placed on granting citizenship to husbands of Qatari female nationals, compared with granting citizenship by male Qataris to their foreign spouses.

Women’s rights violations hit far harder among female foreign workers due to the ease with which they can be deported and the physical circumstances that emanate from living away from family and kin. A particularly gnawing problem is unmarried pregnant women. This phenomenon has much to do with marriage with a foreign worker and risking the loss of a worker’s permit to work in the Kingdom. Pregnancy outside marriage violates the law and deeply engrained religious and social practices. On average, the 100 women facing this predicament receive a one-year jail sentence. The only way out, if available, is if the man in question is willing to marry the pregnant woman. According to a prominent local lawyer, even a verbal commitment is sufficient to rescue the woman from a term in jail. In fairness to the authorities, it should be noted that jail conditions are not onerous; the women are given a choice to have their babies with them and are provided for nutritionally and medically.[8]

By far, the most significant deviation from the progressive bent of AJ+ and the basic concepts of Western constitutionalism and liberalism (in the classic sense) lies in the reality of a non-elected family ruling a majority of residents/workers, some of whom have been living in Qatar for generations, who are disenfranchised. The issue often comes to a head even among the Qatari Arab elite who enjoy citizenship, when the Qatari government readily grants citizenship to foreign athletes to enable them to participate in Qatar’s national teams while denying citizenship to native-born South Asians, many of whom play crucial roles in the social and health systems.[9]

Among Qatari officialdom and citizens, being Qatari means emanating from a pure Arab ethnicity, whose national dress – the thobe for men and abaya for women – “signifies belonging to the exclusive, elitist national population.”[10] Qatari museums devoted to cultivating a modern national identity serve as excellent examples of the exclusion of Iranian and South Asian residents in portraying Qatari national identity.[11]

Analysis of Qatar-Funded Media

Every media site has its ideological preferences and biases, and well-informed American media followers can easily distinguish the way CNN covers women, environmental issues, and religion compared, for example, to Fox News.[12]

To test for biases – our first task – we compared the coverage in Al Jazeera Arabic (AJA) with BBC Arabic, which is part of the BBC network known for its relatively unbiased reporting. Both compete for the same audience – the Arab-speaking world – who overwhelmingly reside in the Arab-speaking states stretching from Morocco in the West to Iraq and the Gulf States. It is important to note that neither AJA nor BBC Arabic has any considerable following in three important Middle East states: Iran, Turkey, and Israel. The vast majority of the Iranian and Turkish population, even those educated, do not know Arabic, except for foreign policy specialists and Muslim scholars, and the small Arabic-speaking minorities in those countries. In Israel, most Jewish Israelis know little to no Arabic, in contrast with the Arabs, who comprise one-fifth of the population and are consumers of AJA.

Qatar funds the Al Jazeera TV and media site in Arabic and AJ+ in English. Furthermore, the almost total lack of advertising on Al Jazeera Arabic and any advertising on the AJ+ site – which operates mainly through Youtube and other social media – suggests that the Kingdom is their only funding source. One would expect thematic consistency in how these two media sites cover events. That, of course, begs a comparison between the content presented on these two channels.

Assessing the Impact of Al Jazeera Sites

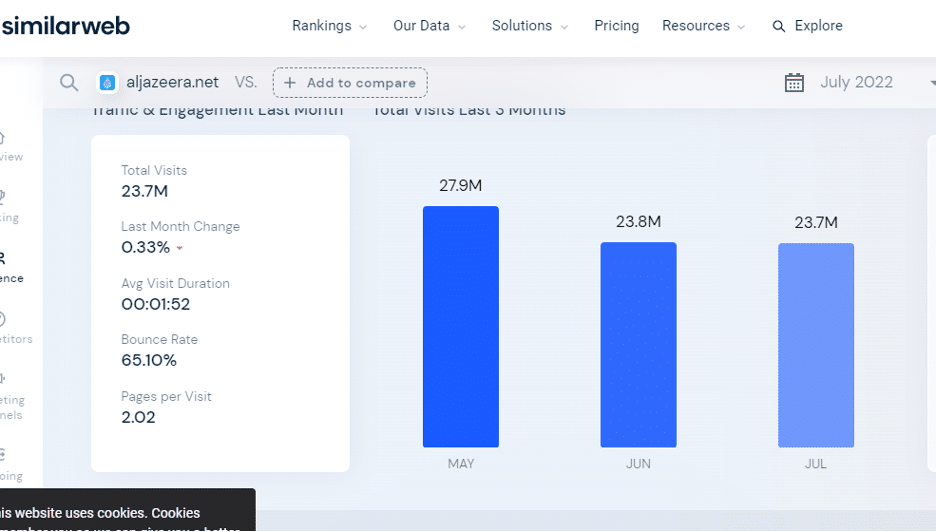

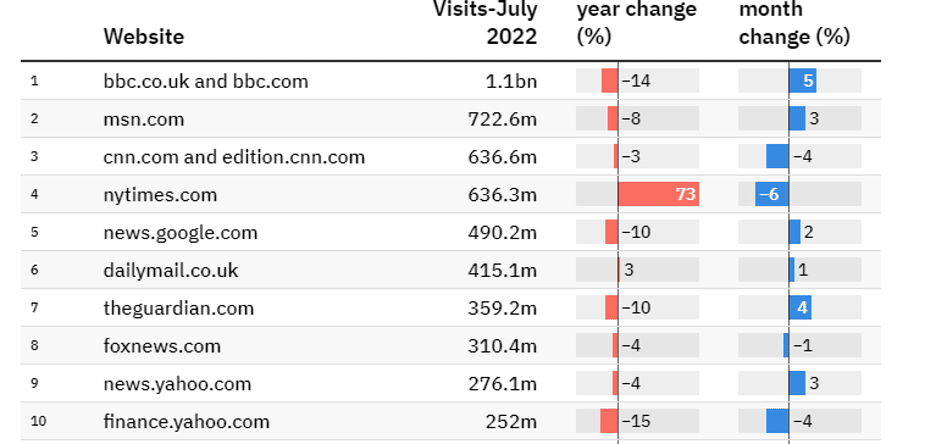

Before comparing the media sites, it is necessary to gauge their relative importance in their respective settings. Looking at the relevant stats regarding Al Jazeera in English (not covered in this study), it is easy to see that despite Qatar’s lavish spending on the media channel, it has failed to become a leading media site among the world media. Similarweb, a site devoted to counting the monthly visits to media sites, reported 23.7 million visits for July 2022, a far cry from the over one billion visits of the BBC giant and not even one-tenth of the number of visits of Yahoo news media, which ranked 10th on the world list, according to the Press Gazette website.

That means the site attracts a minute fraction, well below half a percent of consumers of international news in English.

Assessing the impact of AJ+ is more problematic since their videos appear in several languages, the most important of which is Arabic. From the data provided on YouTube, the primary disseminator of AJ+ content, the overall impact for all languages is modest. Between 2013 and June 2022, their videos registered 315,730,128 views, an average of fewer than three million views a month or one-tenth the monthly views Al Jazeera in English attracts. By comparison, in nearly nine years, AJ+ attracted fewer than one-third of the number of BBC media site viewers in one month.

American consumers, in particular, have not been attracted to Al Jazeera sites, none of which appear in the UK-based Press Gazette’s site top-50 news sites “by number of US visits,”[13] and no Al Jazeera site appears in the top 121 news sites in the US tabulated by Feedspot.[14]

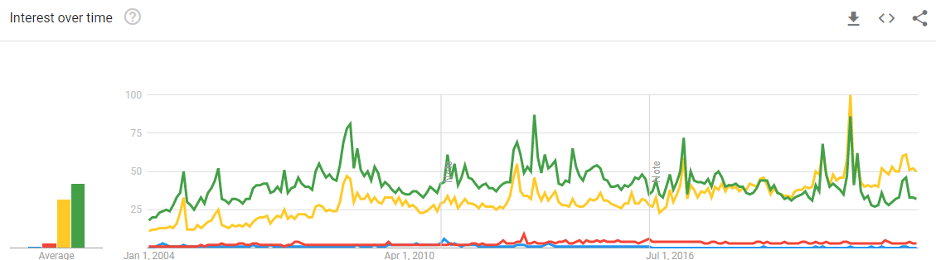

The negligible importance of Qatari-funded media sites in English is further confirmed by Google Trends, which plots searches of content, including media sites. Below are the relative searches in the US for the moribund AJ+, Al Jazeera in English, CNN, and Fox News from 2004, when Google Trends was launched, up to July 2022.

The relative importance of Al Jazeera English, AJ+, CNN, and Fox in the US in Google Trends

Key:

Blue – Al-Jazeera English

Red – AJ+

Green – CNN

Yellow – Fox

Interest in AJ+ and Al Jazeera English is low, constituting only 1% to 2% of the searches on those four media sites. The search scores were 55 for Fox News, 33 for CNN, three for AJ+, one for Al Jazeera English, and less than one for the moribund Al Jazeera America. That means there were at least 10 times more searches for Fox than the Al Jazeera sites combined and six times more searches for CNN than their Al Jazeera counterparts. In sum, Al Jazeera sites carry little weight in US media, with the partial exception of AJ+.

I looked at Google Trends to compare the Al Jazeera sites with the US News Box that appears in the 100th slot of the 121 news sites tabulated by Feedspot. Though the Al Jazeera sites do better, the difference is negligible.

Not surprisingly, there is a positive correlation between the relative popularity of CNN (compared with Fox News) and the relative popularity of the Al Jazeera media sites as reflected in Google search by state in the US, which correlates to Democratic/Republican voting patterns.

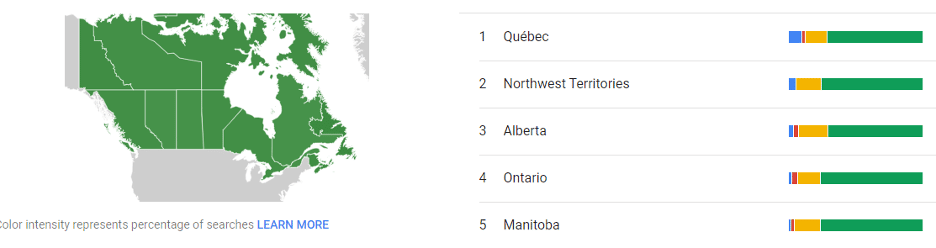

The same findings show up in liberal “progressive” Canada, where the picture reflected by the colors in the chart associated with the four media sites differs from the US. In all of Canada’s provinces, CNN wins hands down against its Fox competitor, but highest for French Quebec in the eastern region than in the more Anglo western provinces. Interest in the Qatar media sites is also far more significant in Canada than in the US (at least double) and relatively more significant in Quebec than elsewhere.

There is a direct correlation between domestic progressive politics and interest in Al Jazeera, which correlates with relative interest in CNN compared with Fox news. Thus, in Quebec, searches for CNN accounted for 71% of all the searches, 16% for Fox, 10% for Al Jazeera, and 3% for AJ+. However, the breakdown for British Columbia is remarkably different, especially for the Qatar-backed media sites: 4% for Al Jazeera and 2% for AJ+.

Though the Al Jazeera media sites score low among audiences in the US writ large, the qualitative impact of AJ+, especially video stories on Israeli “apartheid,” “discrimination,” and “occupation,” might be significant on important sub-populations, such as students in universities in the US.

The 12-minute video, “Americans in Jerusalem Are Helping Kick out Palestinians,” which relates to the violence surrounding the Israeli Supreme Court decision to sanction the removal of Palestinian families on land bought by Jewish societies during the Mandate Period, has been viewed 761,000 times in the space of six months since it appeared on YouTube. Another video, “They Came Here to Attack Arabs: Welcome to Life in Israel’s Mixed Cities,” attracted the same number over a year.

There was no mention in the first video of the lengthy court proceedings leading to the decision, no mention in the second of the 10 synagogues burnt in Lod and Acre (Akko) and the absence of attacks on local mosques, and no mention that 89% of those arraigned and charged for acts of violence within a year of the mass wave of violence in May 2021 were Arab.[15] “Why Israel’s Doomsday Nationalists Want to Destroy This,” meaning the al-Aqsa mosque, was viewed 561,000 times within five months. Videos incriminating Israel seem to be the most popular material produced by AJ+ and easily compete with pro-Israeli videos to attract viewers.

Comparing AJA coverage with BBC Arabic

Five media sites – AJA, AJ+, BBC Arabic, CNN, and Fox News – were analyzed for 60 days between June and November 2022 on content related to nine issues: women, LSBT rights, democracy, discrimination, environment, immigration, religion, Israel, and Egypt. The comparison between AJA and BBC Arabic generated 4,554 items on BBC compared with 3,798 items in AJA. We were interested in comparing the differences over three general areas: the relative focus over Israel (hostile in both, but appreciably more hostile in AJA coverage), conservatism, that is to say, the relative weight given to religion as opposed to more “progressive” concerns such as democracy and human rights, women, the gay community, environment, discrimination, and immigration. The primary hypotheses at the outset of the project were that:

The AJA would focus more on Israel than BBC Arabic.

The AJA would focus more on religion than BBC Arabic.

The AJA would underreport “progressive” concerns, such as human rights, reports on gay issues, and environmental concerns.

All three hypotheses were corroborated, as an analysis of the following data suggests. Below are figures showing the relative frequency of items for these themes in AJA compared with BBC Arabic, considering the close number of total items in both media sites.

| Women | LSBT | democ | discrimin | environ | immig | religion | Israel | Egypt |

| 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.37 | 1.3 | 3 | 2.9 | 0.83 |

Whereas the difference in the coverage of Egypt between the two media sites was relatively small, that was hardly the case regarding Israel, with AJA generating nearly three times more items on Israel and the Palestinians than BBC Arabic.

Moreover, this frequency count does not fully capture the gap between the two media sites. The tenor, length of these items, and the graphic prominence given to the articles on Israel and the Palestinians in BBC Arabic paled compared with the AJA. Striking is the difference in the items focusing on Egypt, the major Arabic-speaking country, with a population of 100 million compared with Israel and the Palestinians, involving at most a combined population of 15 million. In BBC Arabic, the number of items on Israel exceeded those on Egypt by 25% compared with a 290% difference in AJA.

The same can be said, though less glaringly, in their coverage of religious matters. Items on religious practice, festivities and rituals, and ideology appeared on a relative basis three times more frequently in AJA than in BBC Arabic, as one would indeed expect in a media site addressing a traditional Arab audience funded by a monarchy allied with the Muslim Brotherhood, and home to Egyptian-born Yusuf Qaradawi, the militant anti-Israeli Islamic scholar. His death occurred during the period analyzed, and his life and work appeared extensively on the Qatari-funded site.

Quite the opposite was true for the themes championed by the liberal progressive media. Articles on women’s issues appeared less than a third of the time (0.30) in AJA than in BBC Arabic. The exact ratio of underrepresentation in AJA compared with BBC Arabic concerned general articles on democracy and human rights. BBC Arabic published two and a half times more articles relatively than AJA on other progressive concerns such as homosexuality, discrimination, and the environment. Only on emigration was AJA more focused than BBC Arabic by a ratio of 1.3 to 1 – the overwhelming items in both documenting the plight of would-be African and Arab immigrants off the coasts of Spain, Tunisia, Libya, and Turkey in their attempt to reach Europe.

Comparing AJA with AJ+ Coverage

On the AJ+ leading media page, the following passage appears:

A social justice lens on a world struggling for change.

AJ+ is a unique digital news and storytelling project promoting human rights and equality, holding power to account, and amplifying the voices of the powerless.

That is a far cry from how the Kingdom of Qatar, the media site’s funder, is described by Freedom House, quoted early on in the study.

As “a social justice lens of a world struggling for change,” the AJ+ media site should have naturally targeted its funding source, the Kingdom of Qatar, to promote human rights and equality among its overwhelming population of noncitizens devoid of citizenship rights; “holding power to account,” in its treatment of those noncitizens (and occasionally Qatari citizens who would like more democracy); and amplify “the voices of the powerless” majority residing in the country. Of course, none of the opprobrium gets directed toward the Kingdom. However, it is directed abundantly against the US and Israel, where “oppressed” minorities are represented by elected delegates and parties in governing legislatures rather than an advisory council that consists of citizens who form a tiny minority in the country, as in the case of Qatar.

The cynical manipulation of public opinion is evident if one compares the themes brought home in AJ+ compared with AJA, the Kingdom’s significant media venue.

In the previous comparison between AJA coverage and its competitor BBC Arabic, the most noticeable difference was the focus on religion. AJA had three times more coverage on religious matters than its counterpart, accounting for 185 of 3,798 items over 60 days of coverage. By contrast, not one of the 845 mentions of videos presented on the AJ+ media site (usually the same 19 videos) addressed religion over 45 days (until a list of videos ceased to appear on the first page of the site). The focus on discrimination and the environment, and to a less extent on women, was overwhelmingly higher in AJ+ than AJA, much surpassing the ratios seen in the comparison between AJA and BBC Arabic: the ratio was 9-1 regarding women versus five on democracy and human rights, nearly 17 times more on discrimination and immigration, and 80 times more on the environment.

In only one item was there more or less relative equality between the two media sites: the vociferous condemnation of Israel, which accounted for over 10% of the video mentions in AJ+ compared with 7% in AJA.

A notable “progressive” cluster of issues related to sexual difference – homosexuality, LGBT rights, and same-sex marriage – is wholly ignored in AJ+. The Kingdom, which is harsh on homosexuality at home, including the prohibition of same-sex marriage, does not want to be seen advocating such issues on a media site it owns. It also ensures that in none of these videos is there any reference to states close to Qatar, such as Iran, Turkey, and Russia, where discrimination against homosexuals is rife, and violations of other “progressive” issues are widespread.

It is almost laughable to see the qualitative focus of the media site. In its own words describing a video series:

Untold America is a feature documentary show exploring all facets of the American identity – what it is to be American, what it is to become American, and what it is to live as an underrepresented, forgotten, or misunderstood American. The show has explored these questions across diverse landscapes, from tribal lands in Alaska to the streets of San Francisco’s Chinatown to rural landscapes in Texas and Appalachia.

An article on museum creation in the Kingdom, dedicated to creating a Qatari identity, focuses on the almost total exclusion of immigrants from South Asia among the museum’s artifacts, despite a strong presence in Qatar since the 1930s – all of whom are denied Qatari citizenship to this day.

In addition to the video on the tribal lands in Alaska, it might be worthwhile to explore facets of the indigenous population from South Asia in Doha who are consistently denied the ability to become part of Qatar’s national identity.

In the series “Direct From,” correspondent Dena Takruri explores “injustices, turmoil, and conflict impacting our world, takes you to battlegrounds across the globe – to explain the context behind issues, direct tough questions to perpetrators and provide a platform for those afflicted.” The first video featured in the series, “Is the US military prepping for war with North Korea?” with the perception that war against North Korea, arguably the most despotic inhuman regime today, is innately unjust. Takruri should explore the merits of accusations against Qatar by its neighbors, UAE and Bahrain, for supporting the Muslim Brotherhood or radical Shiite subversion.

Judging by the first 10 videos listed, all of which take the US and Israel to task, “injustices, turmoil and conflict impacting in our world” takes place only in the United States or Israel, Judea and Samaria, and Gaza. Of course, with titles such as “Why Israel’s Doomsday Nationalists Want to Destroy This [the Aqsa Mosque],” “How Israeli Apartheid destroyed my Hometown Town,” “They Could Kill Me Anytime: Life Under Israeli Occupation,” and “How the US Navy Poisoned Hawaii Families by Navy Jet Fuel,” one can disregard the continuous wars in Libya, Somalia, and Yemen to mention only a few conflicts where hundreds if not thousands lose their lives annually.

Conclusion

Qatar finances the Al Jazeera Arabic and English media sites and AJ+ in English to incite their respective audiences to either hatred and violence against Israel, in the case of the Arabic media site, or hatred against Israel, in the case of AJ+. The latter promotes “progressive” issues, such as women and minority rights and Black Lives Matter. Intertwined between programs on these subjects appears a heavy dose of vicious anti-Israel coverage mostly related to the Palestinian issue. The focus on the Palestinian issue is out of all proportion to the media focus on the issue in the competing BBC Arabic media site, let alone CNN or Fox news. Promoting hostility toward Israel serves as a means of securing legitimacy for the oil-rich political entity with abundant natural resources, a minuscule number of citizens, and which is vulnerable to many forces that would like to get their hands on its wealth.

Qatar’s manipulation of progressive issues through AJ+ is especially striking given the nature of the Qatar regime: an oil-rich state run by an autocrat whose family suppresses any attempt at democracy, denies citizenship to many inhabitants indigenous to the area (and all the more so to immigrant workers who form the overwhelming percentage of the population), suppresses women and workers’ rights, and considers any form of homosexuality to be illegal and subject to severe punishment. The extent of this manipulation became evident by comparing the “progressive” coverage in AJ+ to the conservative nature of Al Jazeera Arabic coverage. The most striking difference is religion – the second-most important focus of AJA coverage (following the Israeli-Palestinian issue), which was almost totally disregarded in AJ+ material.

[1] freedomhouse.org/country/Qatar

[2] https://freedomhouse.org/country/qatar/freedom-world/2022; اتهامات لقطر بعدم الإبلاغ عن وفيات العمال القاتلة جراء حرارة الخليج June 7, 2022 آخر تحديث قبل ساعة واحدة

https://www.bbc.com/arabic/media-61724579

[4] https://www.business-humanrights.org/en/latest-news/qatar-un-expert-on-racism-highlights-discrimination-stereotyping-and-profiling-of-migrant-workers/

[5] Andy Brown, “It is important that FIFA’s world cup in Qatar gets a human rights legacy,” June 28, 2022 https://www.playthegame.org/news/it-is-important-that-fifa-s-world-cup-in-qatar-gets-a-human-rights-legacy/?utm_source=substack&utm_medium=email

[6] https://www.business-humanrights.org/en/latest-news/qatar-un-expert-on-racism-highlights-discrimination-stereotyping-and-profiling-of-migrant-workers/; https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2021/country-chapters/qatar#:~:text=In%20September%2C%20Qatar%20introduced%20significant,covered%20by%20the%20labor%20law

[7] Leo Sands and John Hudson, “Rainbow-wearing Soccer Fans confronted at Qatar World Cup.” The Washington Post, November 22, 2022 https://www.washingtonpost.com/sports/2022/11/22/rainbow-flag-fifa-soccer-qatar/

[8] Doha News Team, “Facing jail, unmarried pregnant women in Qatar left with hard choices,” August 27, 2013

[9] M.I Al-Hammadi., 2018. Presentation of Qatari Identity at National Museum of Qatar: Between Imagination and Reality, Journal of Conservation and Museum Studies, 16(1), p.3. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5334/jcms.171

[10] Karen Exell, “Desiring the past and reimagining the present: contemporary collecting in Qatar,” Museum and Society, 14. 262. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/331358605_Desiring_the_past_and_reimagining_the_present_contemporary_collecting_in_Qatar

[11] T. B. Fibigerand and M.Daugbjerg, (2011) ‘Introduction: Heritage Gone Global. Investigating the Production and Problematics of Globalized Pasts,’ History and Anthropology 22,144.

[12] Thus, for example, CNN covered issues related to women by a ratio of four to one (231 items out of a total of 5,368) compared with Fox News (37 items out of a total of 10,310 items). By contrast, items on religion appeared on Fox News three times more relative to CNN (33 compared to 5). CNN’s progressive profile can also be seen in its coverage of the environment. For every Fox News item on the environment, five appeared on CNN (64 compared with 23).

[13] https://pressgazette.co.uk/most-popular-websites-news-us-monthly/

[14] https://blog.feedspot.com/usa_news_websites/

[15]”פרסום דוח ביקורת מיוחד בנושא ערים מעורבות”,July 27, 2022 https://www.mevaker.gov.il/(X(1)S(mxyeo4h3yjpeyyfpoxczhs1a))/he/publication/Articles/Pages/2022.07.27-Mixed-Cities.aspx?AspxAutoDetectCookieSupport=1

Photo credit: IMAGO / Levine-Roberts

- בניית אתרים

- בניית אתרים