Israeli settlement in Judea and Samaria must be renewed as a means of imposing costs on the Palestinian Authority for trying to delegitimize Israel, and in response to strategically-placed Palestinian settlement expansion. Israel’s present conflict management approach, which has succeeded in reducing Palestinian terrorism to manageable proportions, is an insufficient response to the dangers of Palestinian territorial expansionism.

For the first time in the one-hundred year old conflict, the Palestinians are beating Israel in the domain it excelled best had had always shown its ingenuity – strategic building and expansion of settlements. This is no longer true. This article makes the case for renewed Israeli settlement in Jerusalem and in strategic areas in Judea and Samaria as the most effective means of imposing costs on the Palestinian Authority for trying to delegitimize Israel, inciting to violence, honoring terrorists and supporting their families. Most of all, renewed Israeli settlement is necessary as a response to strategically-placed Palestinian settlement expansion whose aim is to create political facts on the ground in the Palestinians’ favor rather than entering into negotiations with Israel.

The Palestinians are beating Israel in the domain it had best excelled – settlement.

A policy of selective building in Jerusalem and Judea and Samaria must be a necessary addendum to the present conflict management approach, which has succeeded in reducing Palestinian terrorism to manageable proportions, but has not countered successful Palestinian efforts to build settlements of its own to change crucial strategic facts on the ground with deleterious long-term implications on Israel’s security, particularly in the Jerusalem area and in the southern Hebron hills.

The Problem with Israel’s Conflict Management Policy

Israel’s conflict management approach is based on the assumption that there is no peace partner on the Palestinian side. Should a leader with a considerable popular following and a readiness to accept the “two states for two nations” emerge, the State should embark on a peace process. Until then, Israel has both to take proactive measures such as the three offensives against Hamas in Gaza to deter Hamas attacks against Israel, or in the case of Judea and Samaria, to defend against Palestinian attacks and (at least since the suicide-bombings in the second intifada), to absorb its costs.

Towards the PA, the offensive nightly raids, albeit, in coordination with the PA against a common enemy, Hamas and Islamic Jihad, was supplemented by an economic policy aimed to discourage Palestinian terrorism by allowing differential access to the Israeli labor market. Towns and villages were rewarded with extra permits if they produced little terrorism. These permits are highly sought-after: Palestinian workers working in Israel earn wages double those commanded in the local market even after computing for commuting costs. Permits are often distributed according to the involvement of the places of residence in violence and terrorism.

Seemingly, Israel’s policy has been successful. Hamas has been deterred. In Judea and Samaria and within the green line, Palestinian terrorism has been contained to manageable proportions. One could argue that the wave of Palestinian violence in the fall and winter of 2015 was a test case. 204 attacks were responsible for 35 deaths (between October 2015 and April 2016). A similar amount of attacks yielded at least twenty times that number in the second Intifada that started in 2001. 1 Israel’s nightly raids disrupt the professionalization of the terrorists and their ability to produce lethal explosives and arms.

But managing the conflict alone has also resulted in considerable costs not directly linked to acts of terrorism. Israel hardly interferes with the control over space in Jerusalem and beyond the green line, with long-term implications on Israeli security and the security of its citizens.

While there is a virtual freeze on building in the strategic Maaleh Adumim area in the past decade, the Arabs with funding from Arab states and organizations in coordination with the PA, have created new settlements of their own in Ras Shahada and Ras Khamis near Anata, Al-Za’im and Issawiyeh that number thousands of building units and dwarf Israeli settlement in the area. 2 Many of these buildings are encroaching increasingly on the major road to Maaleh Adumim towards Jericho with threatening security implications in the future. The situation is more problematic in the Hebron region and in the southern Hebron hills.

Public security has probably declined in Jerusalem, in which a freeze of Jewish building in east Jerusalem has been imposed. Few Israelis ply east Jerusalem, Wadi Joz and perhaps even the old city, judging from campaigns launched by the Jerusalem municipality to attract Jewish Israeli visitors to the Jewish cemetery on Mount Olives, the Seven Arcs Hotel and the Old City.

The PA’s Settlement Building Strategy

In the course of nearly one-hundred years of the conflict between Jews and Arabs in the land of Israel, Zionist settlement and the creation of new towns, kibbutzim and moshavim in the new State of Israel ranks as one of the most outstanding achievements of the Zionist movement and Israeli statehood in its conflict with the Palestinians. The settlement project, though hardly linear in its progression or problem-free, encouraged ingenuity, presented a state-building challenge from which a successful Israeli state apparatus was honed, and brought considerable military strategic advantages when the struggle between Jews and Arabs and later the Arab states broke out.

This is no longer the case, neither in Israel within the green line, as the growing Jewish concentration in the “State of Tel Aviv” is reflected in an increasing Arab demographic predominance in Israel’s periphery, and even less so, in Judea and Samaria, where the PA has embarked on strategic settlement building to enhance the prospects of Palestinian statehood and deny Israel important strategic objectives such as the protection of greater Jerusalem and its hinterland.

From the media one can easily get the impression that the PA, the PLO and Fatah, the three mutually reinforcing institutions that bolster Mahmud Abbas’ rule, are almost totally engrossed in internecine fights – against Hamas (and to a lesser extent, Islamic Jihad), and internally within Fatah ranks, against Muhammad Dahlan and his supporters. The PA is also engaged in delicate external balancing acts in its relationship with the Sunni states with which the PA is broadly speaking allied and that these preoccupations come at the expense of strategizing against Israel.

Though one can hardly deny that these issues weigh heavily on the PA’s agenda, nevertheless, the PA has clearly articulated consistent policies that aim to delegitimize Israel in international institutions, to address the world community, especially the US, in pressuring and maintaining a settlement freeze in Jerusalem and Judea and Samaria while it embarks on an aggressive project of building settlements of its own.

Palestinian settlement-building is not aimed to achieve statehood in the immediate future – the security threat from Hamas and Islamic Jihad, requires security coordination with Israel that include nightly IDF raids against supporters and terrorists who are their common foe – but rather to assure that this goal of statehood, with Arab Jerusalem as its capital, will be achievable in the future. Statehood would entail the cessation of Israel’s preventive arrests and raids against nascent arms factories. The IDF and Israel’s security arms are responsible for the lion’s share of these operations.

The PA and the EU, with financial support from Arab states such as Qatar and Kuwait, have over the past decade sought to actively encroach on Israeli rule in Area C. Under the Oslo accords, Israel has exclusive administrative and security control in Area C.

The major arena in this intense yet quiet war extends from Anata (bordering the light rail depot on the northern side of the Jerusalem-Jericho highway) to Abu Dis and Eizariya, three kilometers to the south-east, landing on both sides of the highway parallel to Maaleh Adumim all the way down to Jericho. The PA and EU’s major objective is also their weapon: to create continuous Arab settlement from the south to the north of the West Bank.

Israel would like to prevent that contiguity by building in E1, the area that would create continuous settlement from Maaleh Adumim to Jerusalem. But as Israeli building dwindles into insignificance under the stern gaze of Uncle Sam and a frightened Israeli prime minister, the PA (with the help of the European Union), has succeeded in housing 120,000 Palestinians in a space no larger than nine square kilometers. This number is triple the number of inhabitants of Maaleh Adumim and the other Israeli localities in the area extending to Jericho. And whereas, it took Israel over thirty years to settle 40,000 inhabitants, the PA with European support, have managed to settle triple that number in the course of one decade alone.

Illegal and unauthorized Palestinian building, with the assistance of the EU, is designed to block Israeli development of E1.

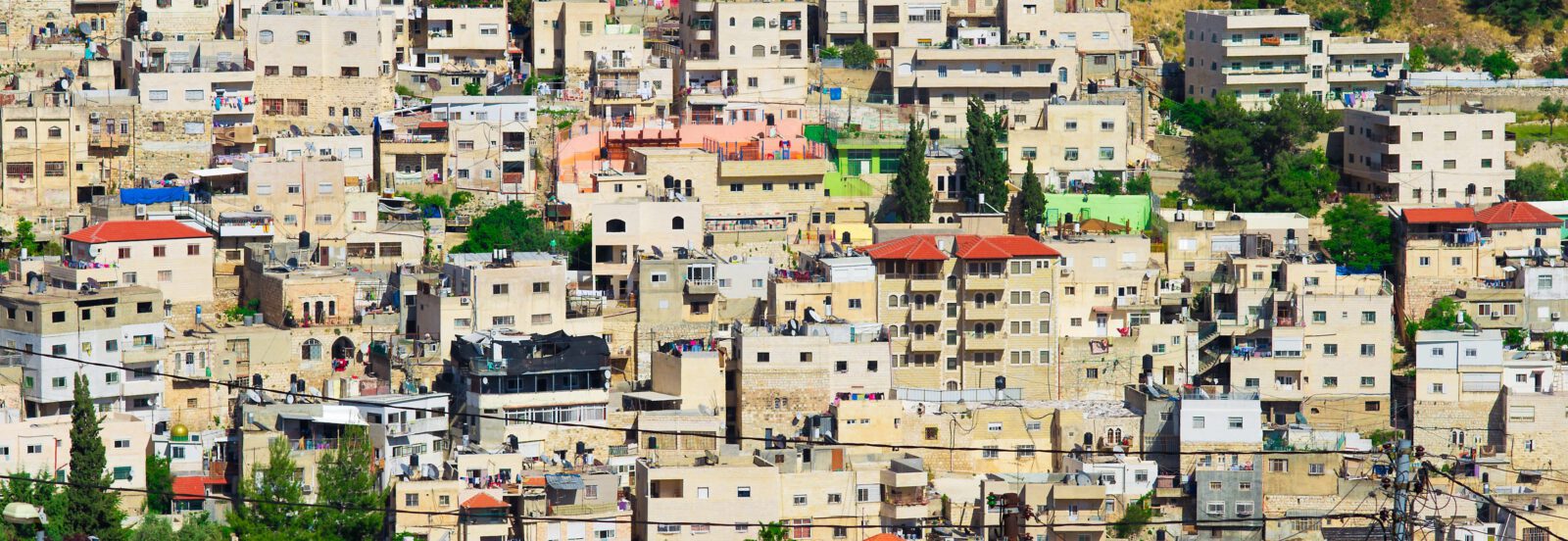

As blindfolded as Israeli officialdom may be in the face of this massive Palestinian settlement drive, this multitude of Palestinian settlers are clearly visible. No driver from the French Hill junction on Route 1 in the direction to Jericho can possibly avoid on his right, one kilometer from the junction and literally meters from the security barrier, the urban jungle of Ras Shahada and Ras Khamis near Anata (in the past called Anatot, from which the prophet Jeremiah prophesized the destruction of the first Temple). According to Palestinian media, Nasrin Alian, an attorney with the Association for Civil Rights in Israel, 120,000 inhabitants live in this urban monstrosity alone, all of which was erected since 2007. Umm Ishak al-Kaluti, of the same media site, confirms that ten years ago she owned one of the few homes on this once barren hill.

Most of this area is within the official municipal line and is thus formally under Israeli sovereignty. The remainder is in Area C, which Israel presumably controls. Yet hundreds of six-to-ten-story apartment buildings were built there, all of which are illegal, as a senior officer in the Border Police in charge of security in the area confirmed.

The Palestinian settlement drive in this strategic area is hardly a showcase of building development. Jamil Sanduqa, head of the makeshift local council of Ras Khamis, supported by the PA and the EU, acknowledges that these neighborhoods are a human disaster or as he put it, “life imprisonment.”

One can hardly dismiss this pronouncement as hyperbole. The only road that traverses this urban nightmare is two lanes wide. It is continuously clogged all the way to the 24-hour outpost, manned by the Border Police, which allows passage into Jerusalem. Fire trucks find it impossible to reach the scene in the event of emergencies like fires from electrical short circuits or explosions of gas balloons (most of which are illegally placed). They would be hard pressed to reach victims in the event of a major disaster like an earthquake.

Garbage burns in the open with devastating health effects on the inhabitants, and probably on the inhabitants of French Hill as well. This is also true of A-Zaim, a smaller version of Ras al-Khamis just two kilometers south-east, which is designated as Area B. In A-Zaim, illegal building is taking place toward the highway in violation of international conventions that stipulate mandatory distances between the building line and major arteries of traffic.

But these urban monstrosities achieve the PA’s three major strategic aims in this vital area, which is why Sanduqa is paid a salary for being there. Together with the tremendous urban expansion of neighboring Issawiyeh on southernside of Route One east-southward towards Abu Dis in Area B, the PA is creating an urban expanse and continuity the PA deems necessary to assure the Palestinian state. The urban expansion of Ras Shahada and Ras Khamis eastward will soon render the settlement of E1 impossible. Both the thrust eastward and southward will choke the development of Maaleh Adumim and threaten its continuity with Jerusalem.

The urban expansion of Ras Shahada and Ras Khamis eastward will soon render the settlement of E1 impossible.

Meanwhile, the EU has identified Bedouin makeshift encampments as the chief weapon for transforming the route to Jericho, once seen as an intrinsic part of the Allon Plan to deny Palestinian statehood, into an area that promotes the width and breadth of the would-be Palestinian state. These fast-growing encampments are too close to a major highway, and bereft of sewage systems and organized garbage disposal. The Israeli authorities have leveled an area just south of Abu Dis that would provide all these amenities, but the EU continues to abet this inhuman settlement. Obviously, the EU believes that any illegal means justify the end of creating a Palestinian state.

The story is being repeated in the southern Hebron Hills. This area constitutes the hinterland of Beersheba where many strategic installations are located.

What Should the Israeli Strategy Be?

Israel’s conflict management approach, buttressed by favorable regional developments, has certainly yielded results that surpass the basic threshold test of success in managing the conflict with the Palestinians. Israel, since the economic and social nadir in 2002, in which over 450 Israelis were killed, has witnessed the longest period of sustained economic growth since the establishment of the State. The process has been characterized by qualitative changes as well: the continued growth and innovation of its high-tech sector, the integration of the latter in more traditional sectors such as water irrigation and agriculture, and the diffusion of higher education geographically and socially into the periphery. Israel is the only OECD country whose demographic growth stems from indigenous higher-than-replacement levels of fertility. Politically, Israel continues to be a vibrant democracy.

Palestinian settlement building, buttressed by Arab states and the international community, has been far more extensive and more strategically placed than Israeli settlement in the last two decades.

Relative success in the war against terrorism should not, however, blind the Israeli leadership from the fight over control of strategic territory. Palestinian settlement building, buttressed by Arab states and the international community, has been far more extensive and more strategically placed than Israeli settlement in the last two decades. If Israeli settlement, especially width-wise, between Jerusalem and Jericho, was supposed to thwart continuity of a future Palestinian state, or better control of a Palestinian state should it emerge, Palestinian settlement, is fast achieving the goal of continuous settlement from Eizariya through Al-Zaim, the huge neighborhoods Ras Shahada and Ras Khamis near Anata and Anata itself, that is effectively undermining the rationale of Israeli settlement in Maaleh Adumim eastward.

Building in E1 that would link Maaleh Adumim to Jerusalem with continuous Israeli settlement, is therefore crucial to even partially rectifying the situation.

Building in E1 that would link Maaleh Adumim to Jerusalem with continuous Israeli settlement, is therefore crucial to even partially rectifying the situation. In the Hebron hills, Israel is caving in to EU-sponsored Palestinian building that is severing strategically placed settlements in the area from the Beersheba hinterland.

The lack of vision implicit in the conflict management approach leads to mobilization patterns amongst both sides that focus over the Temple Mount. The conflict, which always had a strong religious dimension, is increasingly becoming more religious rather than a struggle between a state and a national movement, in part because ideologically motivated Israeli youth are being denied the frontier vision that has always defined Zionism. Denied expanding in the frontier, they center their energies in the Temple Mount.

A similar trend is taking place on the Arab side. The increasing salience of the Temple Mount for the Arabs facilitates Arab mobilization and unity amongst the rank and file. This undermines Israeli control by creating a pan-Palestinian front, in which at two least two relatively quiescent populations in the past, the east Jerusalemites and Israel’s Arab citizens, have moved to the forefront of anti-Zionist and anti-Israeli violence. For 70 years, from the 1936-1939 rebellion up to the first decade of the new century, the Nablus-Jenin-Tulkarem triangle in Samaria played that role. The change can be explained at least partially by the cessation of settlement and the renewed focus on the Temple Mount.

A key failing of the conflict management approach is the failure to impose costs on the Palestinian Authority for trying to undermine Israeli control over Jerusalem, the Temple Mount and the Hebron area. Instead, it makes due with trying to block Palestinian efforts in UNESCO, achieving for the PA membership in the International Court of Justice, the status of member state in the United Nations and moves to deny membership in FIFA because of the presence of Israeli football teams from over the green line in the Israeli federation. The PA hardly pays for initiating these attempts.

Economic sanctions are hardly the answer for two reasons. First, economic prosperity in the PA is strongly correlated with a decline of terrorism. Terrorism in the PA between 2007 and 2012, declined to the lowest levels since the outbreak of the first intifada in December 1987 probably because of the economic growth rates exhibited by the PA. Similarly, the increase in terrorism since then can partially be explained by a strong decline in the growth rate since 2012. Second, economic sanctions are also not viable given the opposition of Israel’s strong economic lobbies who would oppose anything that would harm Israel’s second largest export market. International aid and the value added tax that Israel collects on all imports to the PA basically finance the bulk of the four billion dollars of Israeli exports to the PA.

The answer to the PA’s expansive building in strategic areas lies in the renewal of Israeli strategic building of settlements.

The answer to the PA’s expansive building in strategic areas, its onslaught on Israel abroad, the inflammatory and inciting messages in the media sites and school system its controls, clearly lies in the renewal of Israeli strategic building of settlements. This calls for building in E1, the greater Jerusalem area, in the settlement blocs and in other areas in area C.

The strategy should be twofold. Regardless of what the PA does or does not do, Israel should be more forceful in demolishing illegal construction in area C around Jerusalem, next to important highways such as the roads from Jerusalem to the Jordan Valley, and in area C. israel should also prevent the building of Palestinian infrastructure installations (water, sewage, garbage depots) near Israeli settlements.

The timing of Israeli building should be related to Palestinian misbehavior.

Yet, Israel must also renew Israeli settlements to compete with the PA’s massive change of settlement patterns in key strategic areas. Given the considerable international opposition to such Israeli moves, the timing of these building efforts should be related to Palestinian misbehavior in order to clarify the linkage that unilateral steps by the PA will be met by Israeli state-building.

Facing the International Community

There is no doubt that calling a spade a spade – the need for renewed Israeli selective building in Judea and Samaria to counter the PA’s attempts to alter the facts on the ground – will arouse considerable international opposition. However, there are ways to reduce this opposition.

The first is to clearly point out that the existing international perspective that encourages Palestinian settlement building and expansion while freezing Israeli settlement is a sure way to ensure no progress in the negotiating process. Why should the PA negotiate with Israel when it is achieving its strategic objectives not only under condition of no cost, but in fact being subsidized by the international community to so? The lack of negotiations, in turn, is a clear recipe for instability.

There is much to be distilled from the Oslo agreements and the Quartet Framework that Israel has a right to counter Palestinian building violations in areas B and C, and other violations, such as incitement in the PA’s media outlets and the massive financial support the PA accords to the families of terrorists. Israeli settlement in measured response to these violations is fair means of getting the PA to cease these violations that would contribute to the stability needed to continue the negotiation process.

Israeli Building Strategy and Peace-Making

A policy of Israeli selective building in the territories as a necessary addendum to the existing policy of managing the conflict is designed to facilitate negotiation rather than to serve as an alternative to any peace plan. One should recall that Arafat often acknowledged that his acceptance of political autonomy as an interim state was due most to the feeling that if the PLO did not enter the Oslo peace process in the face of Israeli settlement expansion, there would be no political future for the Palestinians to negotiate.

This sense of urgency has to be reawakened within the PA. The PA must be made to understand, through Israeli construction, that time is not necessarily on the Palestinian side, and that negotiations are necessary to stave off a future smaller and more discontinuous state.

Of course, reawakening this sense of urgency within the PA and PLO is not the only factor in facilitating peace. How Palestinians will weather the succession crisis of its ailing Palestinian leadership, and the inter-Palestinian partition between the PA and Hamas, are important facets of a national movement whose failures far outweigh its achievements.

Meanwhile, Israel has every right to pursue its interests in its historical homeland, part of which it might painfully be willing to share for the sake of peace with a Palestinian entity that genuinely seeks the same.

Photo credit: Bigstock

[1] Oshri Bartal and Hillel Frisch, Are Lone Wolves Really Acting Alone? The Wave of Terror 2008-2015 (Hebrew) May 13, 2017 Mideast Security and Policy Studies, BESA Center for Strategic Studies, pp. 28-9, https://besacenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/MSPS137_HE.pdf

[2] Hillel Frisch, “Knowing your ABC: A Primer to Understand the Different Areas of Judea and Samaria,” The Jerusalem Post, April 23, 2016, http://www.jpost.com/Magazine/Knowing-your-ABC-448963.

- בניית אתרים

- בניית אתרים