A Challenge to Israeli National Security Policy

The construction of the security fence around Jerusalem in 2005 created a civilian, sovereignty, and security challenge in the form of “no man’s land” Arab neighborhoods located within Jerusalem but outside the security fence. No law and order obtains in these areas, and they bases of terrorist activity. This paper proposes establishing a joint administration of the IDF, Israel Police, Jerusalem municipality and the national government to increase governance and security in these neighborhoods, involving investment in education, culture, welfare and employment.

The “Chaos Plan” in the Shuafat Refugee Camp

At 11:30 PM on May 2, 2016, Baha Nababta, 31, head of the young people’s committee in the Ras Shahada neighborhood in northern Jerusalem, one of the Arab neighborhoods beyond the security fence, left with a large group of residents to help pave a road constructed there by the Jerusalem municipality. According to eye witnesses, an unknown person on a motorcycle stalked him. After catching up to Nababta, the rider fired 10 shots at him. Nababta was brought to the hospital and died shortly afterward. Nabata was a unique example of authentic and brave community leadership trying to change something in the harsh reality of the Jerusalem neighborhoods beyond the security fence. His still unsolved murder was but one example of the chaotic situation prevailing in these neighborhoods.

In addition to threatening the lives of these neighborhoods’ residents, this situation also poses a threat to the Jewish and Arab residents of Jerusalem living in neighborhoods within the security fence. The neighborhoods beyond the fence – Ras Khamis, Ras Shahada, the Hashalom neighborhood (Dahiyat al-Salam), the Shuafat refugee camp, Kfar Aqev, Samir Amis, and Al Matar – were used as a home base by approximately half of the terrorists in the waves of terrorism in Jerusalem in 2007-2014. Furthermore, residents of the Pisgat Zeev neighborhood in Jerusalem, adjacent to the Shuafat refugee camp, are occasionally subjected to small-arms fire aimed at their homes from the refugee camp and the nearby neighborhoods.

In October 2016, the Israeli media reported the arrest of six residents of the Shuafat refugee camp on charges of founding an ISIS cell. It is no coincidence that this cell operated in the camp, rather than in other Jerusalem neighborhoods. In his research, Mati Steinberg portrayed the worldview of the global jihad movements and their “chaos program.”1 Steinberg says that these movements deliberately look for flash points lacking governability in which chaos prevails. They intensify their penetration there and set up cells of the organization that aggravate the existing disorder, leading to the collapse of the existing societal and governmental order and the creation of a jihad Islamic governmental alternative there. No place is more suitable than the Shuafat refugee camp for carrying out the global jihad chaos program. The United National Relief Works and Works Agency (UNRWA), which is responsible for the camp, exercises little control there. People from the violent sections of the Palestinian terrorist movements, together with drug peddlers and criminal gangs, exercise control there by brute force.

Discussing the issue of the Jerusalem neighborhoods outside the security fence and finding a civilian and military solution to the threats they pose to Jerusalem is therefore not a purely civil matter; it is also a challenge to Israel’s national security. The question of sovereignty also arises, given the absence of Israeli rule in these neighborhoods. Activity by the Palestinian Authority (PA) is more prominent in these neighborhoods than in other neighborhoods in eastern Jerusalem, including kidnappings by the PA security agencies, with the victims being brought to nearby Ramallah for interrogation; providing municipal services not available from the Israeli authorities, such as garbage collection; PA policemen directing traffic; etc.

The purpose of this paper is to highlight and specify the challenge that the situation in these neighborhoods poses to Israel, to consider and propose alternatives for Israeli policy on the matter, and to present recommendations for action.

Creation of the Security Fence in the Jerusalem Area – Historical Background

The first decision about building a separation fence, including a fence surrounding Jerusalem, which was not implemented, was taken following the terrorist attack at Beit Lid in 1995. Proposals for construction of a fence were also made during the period of the Barak government, but these were again not carried out. The public campaign for building the fence began with the “Fence for Life – Public Movement for the Security Fence,” founded in June 2001 after the terrorist attack at the Dolphinarium when the Sharon government was in power. Following suicide attacks that resulted in hundreds of fatalities, public support for a separation fence grew. The government accordingly approved construction of the separation fence in April 2002, although its location and the specifics of its construction were not stated.

In June 2002, the first stage of the fence around Jerusalem was approved, including two 10-kilometer sections. The first, located in northern Jerusalem, stretched from Ofer Prison in the west to the Kalandia barrier in the east. The second, located in southern Jerusalem, stretched from Highway 60 (the Tunnels Road) in the west to Beit Sahour (south of Har Homa) in the east. These two sections were completed in July 2003. Three more sections were approved in September 2003. The first, 17 kilometers long, stretched from Beit Sahour in the south to east of Al Azariya in the north. The second, 14 kilometers long, stretches from Kfar Anata in the south to the Kalandia barrier in the north. The third section, also 14 kilometers long, connects Ofer Prison in the east to Givat Zeev in the west. In February 2005, the government approved a 40-kilometer addition in the area of Maalei Adumim and Gush Adumim. In August 2008, then-Prime Minister Ehud Olmert decided to reduce the area of Maalei Adumim that would be included in the fence according to the plans.

The considerations that led to the construction of the fence primarily concerned security:

- Preventing free and uncontrolled passage of Palestinians between Judea and Samaria and Jerusalem.

- Preventing penetration and smuggling of explosives into Jerusalem.

- Preventing penetration by car bombs.

Leaving the Shuafat refugee camp and the surrounding area outside the separation fence was related to the fact that the camp was actually managed by UNRWA, which was responsible for handling the Palestinian refugees. The existence of an international agency providing services probably made it easier to cut off these neighborhoods from Jerusalem. As for Kfar Akev, it was probably left outside the fence also because the terrain made it impossible to put the barrier between Kfar Akev and southern Ramallah, and because the population density in the area increased friction with the Israeli security forces and was liable to pose a severe tactical limitation.

In addition to the security and geographic consideration, it can be assumed (although there is no confirmation of this from the elected leadership) that the location of the fence also involved a demographic and political consideration concerning a future permanent or temporary settlement with the Palestinians that would change the boundaries of Jerusalem and leave tens of thousands of Palestinians outside these boundaries.

In 2002-2004, a series of terrorist attacks occurred in Jerusalem, including dozens of suicide attacks, that resulted in 208 fatalities, including women and children, while 1,624 people were wounded and disabled. Since 2004, and especially since 2005, the number of terrorist attacks in Jerusalem fell substantially. Even if there were other material reasons, including Operation Defensive Shield in 2002 and the death of Yasser Arafat in November 2004, the Israeli public regarded the timing of the decrease in attacks as proof of the barrier’s effectiveness.

In 2004, when construction of the separation fence around Jerusalem was completed, residents of the Shuafat refugee camp, Ras Khamis, Ras Shahada, the Hashalom neighborhood, Za’ir, Al Matar, and Kfar Akev found themselves outside the fence. The same was true of residents of Walaja in southern Jerusalem. On the other side, another group of residents, such as the residents of Dahiat El Barid adjacent to Beit Hanina, who are not within the Jerusalem municipal boundary (meaning that they are not legally residents of the city), found themselves “imprisoned” within the separation fence. Construction of the fence in Jerusalem was completed in 2005, and the situation has remained this way ever since.

The Gap between the Municipal Boundary and the Separation Fence

Construction of the fence resulted in a lack of congruence between the municipal boundary and the security fence. Two types of enclaves were created: area outside the security fence, but within the municipal boundary, and area within the fence, but not included in the city’s jurisdiction (see the maps illustrating the matter in Appendices No. 1 and 2).

The following are prominent enclaves outside the fence and within Jerusalem’s municipal jurisdiction:

- The vicinity of Walaja in southern Jerusalem – 500 dunam (125 acres), including residences.

- A 900-dunam (225-acre) area that contains the entire Shuafat refugee camp and the neighborhoods of Ras Khamis, Ras Shahada, and Hashalom. Construction in this area is very dense, with many buildings.

- A 1,300-dunam (325-acre) area in northern Jerusalem that includes all of Kfar Akev, Al Matar, Za’ir, and Kalandia.

The area outside the security fence, but within Jerusalem’s municipal jurisdiction, totals 3,430 dunam (857.5 acres) and contains 120,000-140,000 residents.

The following are the most prominent of the other type of enclave – areas outside the Jerusalem municipal jurisdiction, but inside the fence:

- A 700-dunam (175-acre) area including Har Gilo and the entire surrounding area.

- A 400-dunam (100-acre) area in Wadi Hummus in the vicinity of Deir Al-Amud, and Dir Al-Mintar in southeastern Jerusalem.

- A 1,500-dunam (375-acre) area east of the Neve Yaakov neighborhood.

Approximately 7,000 people live in the 9,690-dunam (2,422.5-acre) area outside the municipal boundary but inside the fence.

The Jerusalem municipality is responsible for providing civilian services and municipal law enforcement and supervision to residents of the areas inside Jerusalem’s jurisdiction, but beyond the separation fence. The IDF Civil Administration is responsible for providing civilian services and municipal law enforcement and supervision in areas outside Jerusalem’s boundaries, but inside the separation fence.

The Jerusalem municipality has difficulty providing proper services and exercising sovereignty in areas outside the fence, due to the need for armed forces to accompany those providing these services. The Civil Administration also has difficulty in providing services in areas beyond the municipal boundary. These problems pose a difficult humanitarian, security, sovereignty, legal, and law enforcement challenge to the municipality and the state (the IDF, the Ministry of Defense, and other government ministries); the current division of responsibility between the municipality and the state (the Civil Administration) does not provide an adequate solution.

In policing and security, under a cabinet resolution dated April 30, 2006, the IDF was made responsible for internal security in neighborhoods within Jerusalem’s boundaries, but outside the security fence, while Israel Police retained responsibility for public order. The IDF is therefore responsible for security in the Kfar Akev area and Israel Police are responsible for public order there, while the Border Police are responsible for internal security in the Shuafat refugee camp and the surrounding area and Israel Police are responsible for public order there.

In the event of an emergency (such as an earthquake) or the collapse of one of the innumerable illegally constructed multi-story buildings tightly packed into the Shuafat refugee camp and the Hashalom, Ras Khamis, Ras Shahada, and Kfar Akev neighborhoods, the Home Front Command will have to operate in a location where Israel’s security agencies are largely absent and there are no established procedures for dealing with the physical and cultural challenges that it poses. Construction there is undocumented, and there are no proper urban building plans describing the built-up area – a necessity for devising a proper rescue plan.

The Demographic Consequences of the Lack of Congruence between the Municipal Boundary and the Separation Fence

Before the fence was built, Palestinian residents of Jerusalem were free to immigrate outside the municipal boundaries, and commercial centers and housing were built for them in neighborhoods. The most prominent of these was A-Ram, where 60,000 residents lived before the fence was built. Most of A-Ram’s residents had documents listing them as Jerusalem residents. Few people now live in A-Ram, which features little of its former lively commerce and economic activity.

Following the construction of the fence, tens of thousands of Palestinians thronged into parts of Jerusalem inside the fence, fearing that the municipal border would be redrawn according to the fence’s location, thereby depriving them of their Jerusalem resident status. They were also worried that the fence would detract from freedom to move in and out of Jerusalem, with all of the resultant negative consequences (mainly in jobs and services).

At a later stage, when the residents realized that Israel was in no hurry to concede the neighborhoods outside the fence and was leaving them within Jerusalem’s municipal boundary, even larger masses of people began moving into the Arab Jerusalem neighborhoods outside the fence. The resident who moved inside the fence from A-Ram or Bir Nabala out of fear of losing their Jerusalem resident ID cards returned a few years later to Kfar Akev and the area around the Shuafat refugee camp.

To these “returning residents” can be added thousands of Palestinian “move-up buyers,” who prefer buying a 120-sq.m. apartment in Kfar Akev for $60,000 to a similar apartment for at least $300,000 in the nearby Beit Hanina neighborhood inside the fence.

Since there is no partition, barrier, checkpoint, or boundary between PA territory and the Jerusalem neighborhoods outside the fence, illegal residents frequently move into the neighborhoods outside the fence, causing a continual increase in the number of Arab residents living in Jerusalem.

The Current Situation in the Neighborhoods outside the Fence and its Consequences

One July 10, 2015, the Sharon government issued Cabinet Resolution 3873 for regulating the situation of residents outside the fence (see Appendix 4). The government announced a special budget allocation for the Jerusalem municipality for arranging open market areas near the crossings, maintaining public order, encouragement of medical services beyond the fence, establishment of postal units near the crossings, establishing employment branches, humanitarian crossings for medical patients, establishing units of various government ministries, transportation to schools for students, special grants for implementing the decisions, and establishment of a special community administration for these neighborhoods. Today, 13 years after the cabinet resolution, most of these measures have not been implemented.

The construction of the separation fence in 2004-2005 posed an extremely difficult challenge to the Jerusalem municipality and the Israeli authorities: maintaining continuity of services and management of daily life in a state of separation and disconnection. This difficulty extended to planning and building, operations, infrastructure, education, welfare, public order, law enforcement, and other spheres. The two types of areas discussed in this article suffer from an array of problems resulting from lack of control, the most prominent of which are as follows:

- Large-scale illegal construction preventing any possibility of developing proper infrastructure for the neighborhoods;

- Constructions on top of roads and in areas zoned for public buildings, which makes it impossible for the authorities to maintain a reasonable standard of living for the residents;

- Extremely poor basic services, especially sanitation (representatives of the neighborhoods involved filed a lawsuit about sanitation against the Jerusalem municipality and the state of Israel in 2015);

- Prevalence of crime and public disturbances;

- Activity by terrorist groups and extreme anti-Israeli nationalistic groups;

- A shortage of public, health, and educational institutions;

- A shortage of basic road infrastructure;

- Very crowded conditions, including a large number of illegal residents, resulting in enormous burdens on already inadequate civil services and infrastructure;

- An absence of safety control, sewage and drainage services, and traffic facilities.

The neighborhoods outside the fence have become “cities of refuge” for criminals fleeing from the PA’s security and law enforcement organs. These criminals pose policing and security challenges to Jerusalem, including inside the fence. For example, many crimes in Jerusalem originate in neighborhoods outside the fence, and about half of the terrorists in the 2007-2014 wave of terrorist attacks came from these neighborhoods.

From a socioeconomic standpoint, these neighborhoods have become slums, even though some of their residents are middle-class (a large proportion of middle-class people moved to nearby Beit Hanina over the years). Illegal drugs, alcohol, violence, and dis-functional families are common in these neighborhoods. Criminal gangs have zeroed in on various businesses and illegal construction. In Kfar Akev, the effective rulers are members of the Tanzim (the military branch of the Fatah movement) from the nearby Kalandia refugee camp. The situation in the Shuafat refugee camp is more complicated: the Tanzim are not present, but the strongest groups are mainly criminal gangs.

These fundamental problems will only worsen with time. For example, illegal construction and absorption of masses of new residents in the Shuafat refugee camp and its vicinity (in the Jerusalem municipal jurisdiction, outside the fence) and the Wadi Hummus area (outside the Jerusalem municipal jurisdiction, inside the fence, see Appendix 2) is assuming unprecedented proportions, which will further aggravate the above-noted trends. The lack of law enforcement by the Jerusalem municipality in the neighborhoods outside the fence and by the IDF Civil Administration in neighborhoods outside Jerusalem’s jurisdiction and inside the fence, due mainly to physical barrier created by the fence in the Civil Administration’s activity in Judea and Samaria outside the fence, are facilitating lawlessness and rule of brute force in these areas.

The residents estimate that Kfar Akev, where 15,000-20,000 people lived before the fence was built, now has 40,000-50,000 residents. A similar population increase took place in the area of the Shuafat refugee camp after the fence was built in 2004. The most prominent result is in planning and building, due to the stark contrast between the number of residents in the neighborhoods and the ability of the area to absorb them. There are few building plans in Kfar Akev, and most of those are isolated and by private developers. No action has been taken on many plans for which files were opened, and many plans were shelved. The vast majority of Kfar Akev was consequently constructed without an urban building plan.

The Jerusalem municipality began promotion of two outline plans in the Shuafat refugee camp, but these were discontinued. The few existing plans are by private developers on small lots. Files have been opened for a total of 24 plans, three of which were approved. In effect, as in Kfar Akev, there is no planning in the entire Shuafat refugee camp.

These neighborhoods also suffer from an absence of sovereignty and law enforcement. Almost no construction supervision has taken place there in recent years. The reasons for this state of affairs lies in both security constraints and constraints by senior government officials imposed on the Jerusalem municipality for diplomatic reasons in demolishing illegal houses in eastern Jerusalem. This situation has resulted in widespread high-rise construction that is largely illegal and lacking in basic infrastructure. Dozens of buildings spring up everywhere in neighborhoods outside the fence with no oversight. Many signs in the streets advertise extremely cheap new residential projects.

This widespread illegal building takes up space that could have been used to develop decent facilities for the residents, such as public gardens; educational, welfare, and cultural institutions; and roads. Public spaces and children’s playgrounds are being displaced by junkyards selling left-over scrap metal. Illegal building is also extremely frequent in “mirror images” of Kfar Akev and the Shuafat refugee camp, such as Wadi Hummus and similar places (see Appendix 3 for a picture of illegal construction).

The Knesset Internal Affairs and Environment Committee addressed the question of illegal construction in Kfar Akev in eastern Jerusalem in January 2012. Adv. Amir Fisher, legal adviser of the Regavim movement, who filed a petition against the state, described in the committee hearing a depressing situation in eastern Jerusalem, specifically Kfar Akev, where he said, “The law has not been enforced for 15 years.” In response to Regavim’s petition, the State Attorney’s Office described the difficult situation in the area. “The security situation in the area is complicated, being greatly affected by the proximity of these areas to Judea and Samaria. Security forces operating in the sector are exposed to violent clashes and demonstrations, stone-throwing and Molotov cocktails, road blockades, pipe bombs, and so forth.”

The State Attorney’s Office added that the Jerusalem Local Planning and Building Commission bore responsibility for enforcing planning and building laws, and that in view of the security situation in the area, no inspectors had entered Kfar Akev for over 15 years. The written response by the State Attorney’s Office stated that a full-scale military force would have to enter Kfar Akev and remain there for several weeks in order to enable inspectors to safely examine the location and buildings. “This will require allocation of huge resources solely to this problem and divert the security forces’ attention from other more important missions, including regular security operations and escorting police forces engaged in enforcing the law against offenses that pose a far greater risk.”

In short, the state answered that the problem in Kfar Akev was known, but was not a high priority because of the resources required in order to enforce the law: “As for the handling of priorities in the enforcement of planning and building laws for buildings constructed without a permit, in view of the existing security situation, priority in law enforcement is given to more severe offenses than planning and building violations.”

Over the past three years, Israel Police, led by the Border Police, have conducted a series of significant actions aimed at bolstering law and order and thwarting terrorism originating in the Shuafat refugee camp and the surrounding area, including frequent entry into the area to deal with complaints by residents about violence in the family and combined action with the Jerusalem municipality in registration of businesses, the sales of defective food products, etc. The Jerusalem District Police have also established a combined policing center at the Shuafat crossing in cooperation with the Jerusalem municipality and the community administration operating on the municipality’s behalf in the area. The municipality is also repairing roads, lighting, sidewalks, and other infrastructure on a larger scale than previously. It is nevertheless clear that that the municipal actions being taken are negligible in comparison with the enormous need to improve conditions affecting every aspect of life.

In education, there are 30 schools in Kfar Akev and its neighborhoods (Samir Amis, Al Matar, Za’ir, Kalandia) and the Shuafat refugee camp and its surrounding area (Hashalom, Ras Khamis, Ras Shahada). Some of these have official recognition from the Ministry of Education and the Jerusalem municipality, while others have unofficial recognition and are partly funded by the Ministry of Education. Some are private schools, including those run by Christian and Muslim groups, while UNRWA operates schools in the refugee camp. In the Bir Onah and Walaja neighborhoods in southwestern Jerusalem, the students learn at PA educational institutions.

Due to the shortage of buildings for education, the Jerusalem municipality is forced to rent buildings for educational institutions, and to run a system for transporting thousands of students every day to schools in neighborhoods outside the fence.

The difficult issue of UNRWA recently made headlines, including the classification of Jerusalem residents as refugees, incitement to violence in its schools, the low level of sanitation services provided by UNRWA, etc. Towards the end of Mayor Nir Barkat’s term in office, the Jerusalem municipality began a general campaign to replace UNRWA’s services with municipal services. It is to be hoped that this campaign will be continued during new Mayor Moshe Leon’s term.

A comprehensive look at municipal activity shows that it is totally non-existent in many areas because of security constraints, while being inadequate in other areas, in view of the large population involved. This situation perpetuates, and even accelerates, the decline in living standard and the level of municipal services. This paper seeks to alert readers about both the humanitarian and legal aspect – an obligation to the residents – and the cumulative consequences of this situation for public order, crime, and security, as well as the legitimacy of Israeli rule in the united city and the PA’s efforts to undermine it.

Alternative Government Policies on the Issue

Concerning the neighborhoods outside the municipal boundary but within the security fence (such as Wadi Hummus), there are three main alternatives. The first is maintaining the current situation, which will escalate the negative trends described above. The second is enabling the Civil Administration to govern there by allocating the necessary forces and money. The third is transferring responsibility for the area to the Jerusalem municipality, with reimbursement from the state for the personnel needed and the services to be provided to the thousands of residents living in these areas, the most prominent of which is Wadi Hummus, located next to the Zur Baher neighborhood.

Anyone traveling along the existing line between Zur Baher and Wadi Hummus will notice the substantial improvement in services in Zur Baher. In recent years, there have been many legal housing starts with urban building plan approval and building permits (the Local Planning and Building Commission approved the masterplan for Zur Baher in November 2017), construction of public institutions, roads paved, sanitation improvements, and more. It is obvious that this progress disappears once the boundary is crossed. It is better to allow the Jerusalem municipality to extend this progress to nearby Wadi Hummus and apply the law there before the situation becomes irreversible.

The best way of dealing with this area is therefore to transfer responsibility for it to the Jerusalem municipality and the Jerusalem District Police, with the addition of more personnel, money, and authority. Implementation of this policy obviously requires a government decision authorizing the Jerusalem municipality to deal with these areas and then granting it the appropriate tools for this task.

The areas outside the fence, with their 120,000-140,000 residents, are obviously a more difficult problem. Alternatives for dealing with it include the following:

- Maintaining the existing situation, with all its consequences.

- Handing over the area to PA control, either unilaterally or in the framework of an agreement between the two sides. Given the major security challenge that this will pose to Jewish neighborhoods close to the PA, such as Pisgat Zeev; the weighty political consequences (under the Basic Law: Jerusalem, the Capital of Israel) of changing the city boundaries or transferring sovereignty in Jerusalem’s territory to another party; and the current deadlock in negotiations with the Palestinians; this alternative is probably off the agenda. The situation of the residents in these areas is liable to remain extremely poor under PA rule. Furthermore, residents of these areas who have Jerusalem identity cards (probably two thirds of the residents) are likely to crowd into the Arab neighborhoods within the fence, thereby placing an additional burden on those neighborhoods’ already overloaded infrastructure.

- Minister of Jerusalem Affairs and Heritage Zeev Elkin has proposed establishing two different municipal authorities: one authority for the Shuafat refugee camp and its vicinity and another authority for Kfar Akev and its vicinity, separate from Jerusalem, but under Israeli sovereignty. The new authorities will initially operate as appointed external committees consisting of professionals managing neighborhood affairs. This alternative involves first of all changing Jerusalem’s municipal boundary, which is politically and constitutionally difficult. It should also be kept in mind that appointing committees to run local authorities, a model used in the Israeli Arab sector for many years, did not result in efficient administration; the Ministry of the Interior stopped appointing such committees for Arab communities and replaced them with an independently elected local government administration. It is likely that a model that failed in Arab communities within Israel will also fail in a much more complicated and difficult place like the Shuafat refugee camp.

- A change in the location of the fence to make it correspond to the municipal boundary. This will require disassembling and reassembling the fence, which will involve great technical, engineering, monetary, and political difficulties.

- Leaving the municipal boundary unchanged and redistributing responsibility for providing services, so that the municipality will provide services inside the fence, including areas outside the municipal boundary (such as Wadi Hummus), while the Civil Administration will provide services in areas outside the fence within the municipal boundary as a continuation of its activity in Judea and Samaria. This alternative is being discussed by representatives of the municipality and the Civil Administration, which has posed two preliminary conditions for that are unlikely to be fulfilled: approval by the elected political leadership; and devising a legal formula that will enable a military agency to provide civil services to Israeli residents within Jerusalem’s municipal boundary. The practical effect of this alternative will be provisions of services by PA agencies in neighborhoods such as Kfar Akev, albeit in coordination with the Civil Administration and under its supervision. What it amounts to is a type of Palestinian government in the areas of Jerusalem beyond the security fence. This will be unacceptable to the Israeli government as long as it insists on Israeli sovereignty in all of Jerusalem.

- Creating a security escort agency to enable employees of the Jerusalem municipality or the contractors operating on its behalf to work regularly and safely in neighborhoods beyond the fence and allocating enough extra money to the Jerusalem municipality for the extensive services it will have to provide to the tens of thousands of illegal residents there within its municipal jurisdiction.

- Creating a new joint administration for managing the affairs of these neighborhoods that includes the Jerusalem municipality, the IDF, Israel Police, and the Israeli government. The Israeli government will lead the new administration (the National Security Council will be responsible for strategy and the Ministry of Jerusalem Affairs and Heritage will be responsible for administration. The new administration will operate separately from the municipality as an independent agency with a separate budget and independent operating capabilities.

An Analysis of the Alternatives and Recommendations for Action

Since implementation of the alternatives requiring a change in the political situation or a change in the Jerusalem’s municipal boundary is unlikely, and given the legal and political difficulty involved in redistributing responsibility for providing civil services between the Civil Administration and the Jerusalem municipality, the feasible alternatives on the agenda are finding a solution within the framework of the Jerusalem municipality and creating a special administration for the purpose. During 2018, when I was the adviser to the Jerusalem municipality on eastern Jerusalem affairs and the leader of the municipality’s team for eastern Jerusalem, we considered the possibility of establishing a special “quarter” for neighborhoods outside the fence.

Seven different quarters are delineated in Jerusalem, and each one of them has a planner responsible for planning and engineering matters and a manager responsible for operations. The municipality’s proposal was to set up a new separate municipal quarter that would focus on the neighborhoods discussed in this paper. The municipality emphasized that if such a plan materializes, it would have to be based on a large separate budget that would enable it to act to change the living conditions there. Without such a budget, the manager of the quarter and his team will be unable to perform any actions on the ground. Despite the advantages of applying the existing “quarter” model, with the experience accumulated in utilizing it, to the neighborhoods in question, a separate organizational framework that includes governmental and security agencies and the municipality should be presented.

The fundamental problem of the neighborhoods in question concerns governmental issues that go beyond the municipality’s authority and capabilities. The planning and building question, for example, does involve the municipality, but the authority to make planning decisions rests with the Jerusalem District Planning and Building Commission and the District Planning Office in the Ministry of Finance. Security and police activity are in the hands of the IDF and Israel Police. Furthermore, the question of the uncontrolled population growth in these places resulting from illegal residents is definitely beyond the municipality’s authority.

Previously discussed proposals for dealing with this demographic problem dealt mainly with instituting security checks between Judea and Samaria and Jerusalem, but justified humanitarian concern about the consequences of blocking movement in either direction between Judea and Samaria and Jerusalem resulted in the rejection of this solution.

In view of the governmental character of the challenge, the best organizational solution is therefore the creation of a joint administration that includes the IDF, Israel Police, the municipality, and the government operating in coordination and synchronization to bolster governability in these neighborhoods. Merely establishing the authority will obviously not lead to concrete progress in dealing with the challenge unless adequate personnel resources and a suitable independent budget are allocated. Another factor that must not be ignored is that finding solutions to the existing challenges in the neighborhoods in question and managing day-to-day life there also involves regular dialogue with the PA, which is virtually adjacent to these neighborhoods, with no barrier separating it from them. Israel’s national authorities, with all of the agencies for civilian and security coordination with the PA, have far more experience in these matters than the Jerusalem municipality.

In planning and building, the most difficult question, a joint think tank should be established, with participation from the best urban planners in the private market, representatives of the local neighborhood committees, and the planning and building authorities in the municipality and the government, aimed at devising creative solutions for the existing situation. It will be very difficult to apply regular urban renewal models in the Shuafat refugee camp and the surrounding area, given the extreme crowding of the buildings and the almost complete lack of available land. In contrast, parts of Kfar Akev can still be “rescued” with conventional urban planning.

Due to the poor state of infrastructure, some of which is probably irreversible, it is proposed that most government and municipal investment focus on human capital, with an emphasis on investment only in Jerusalem residents (those having Jerusalem identity cards), not the illegal residents. Investment of this type can include large-scale educational programs for encouraging continuation of studies and reducing the number of dropouts, opening centers for employment guidance, developing programs for helping people escape poverty and become economically independent, promotion of welfare solutions, etc. The civilian response is dependent on continuous and effective security and police work, including intensive operations to remove illegal residents living and acting in the area, who constitute a burden on the local civilian infrastructure. Most of the government agencies dealing with the matter believe that at least one third of the 120,000-140,000 residents of these neighborhoods are illegal residents.

Finally, the challenge described here is not confined to one agency. The many years of total neglect have generated an extremely difficult situation that poses a major challenge to the security of Jerusalem. This paper calls on Israel’s elected leadership to find the time necessary to address this weighty issue, starting with setting time aside for a cabinet discussion at which comprehensive staff work led by the National Security Council in recent years is presented. Postponing dealing with the matter will only worsen the existing trends on the dividing line between Judea and Samaria and Jerusalem, where the dire governmental situation is creating an incubator for terrorists. As noted above, half of the terrorists in the recent waves of terrorism came from these neighborhoods. As recently as December 13, 2018, a terrorist residing in the Kalandia refugee camp near Kfar Akev committed an attack on Hagai Street in the Old City of Jerusalem. The elected political leadership should therefore take note of need to address the difficult and urgent question presented in this paper.

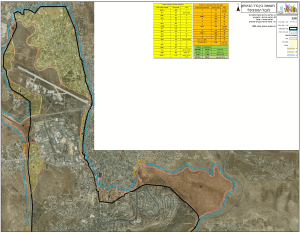

Appendix No. 1 – Map of Northeastern Jerusalem

The Kfar Akev area is marked in green-yellow in the upper-left of the picture. The route of the fence is marked in red and white.

(Source: Jerusalem municipality. The figures in the tables for the numbers of residents are not up-to-date).

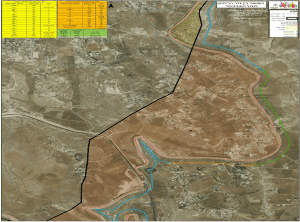

Appendix No. 2 – Map of Wadi Hummus in Southeastern Jerusalem

The area outside the municipal boundary and within the security fence.

(Source: Jerusalem municipality. The figures in the tables for the number of residents are not up-to-date).

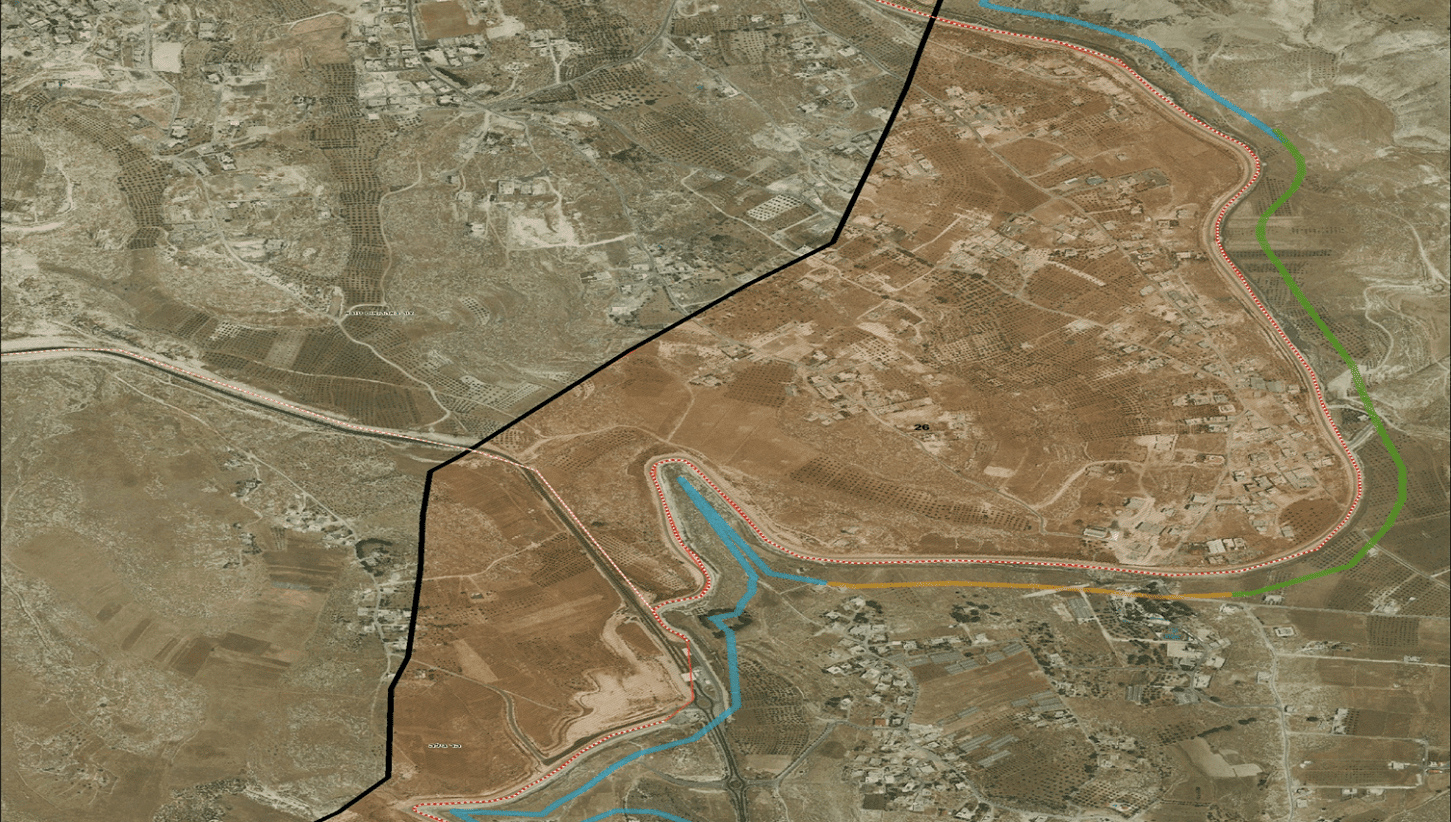

Appendix No. 3 – Picture Portraying the Grave Situation in Sanitation and Illegal Construction

In the Ras Shahada neighborhood adjacent to the Shuafat refugee camp. (Photographed by the author of this paper).

Appendix No. 4 – July 2005 Israeli Cabinet Resolution 3873 on the Jerusalem Security Fence

Resolution No.: 3873

Source: Prime Minister’s Office

Unit: Cabinet Secretariat

Date of Publication: July 10, 2005

Cabinet Resolution No. 3873 dated July 10, 2005

Subject of Resolution: Preparations by government ministries on the Jerusalem security fence and handling of the population in the Jerusalem area as a result of the fence’s construction

It is decided:

- The government of Israel regards immediate completion of the security fence in the Jerusalem area as very important for improving the personal security of residents of Israel in general, and residents near the boundary of Jerusalem in particular.

- The government ministries shall complete their preparations for providing services as described below by September 1, 2005 within the approved budget framework:

- Jerusalem municipality

- Establishment of a “Jerusalem Boundary Community Administration” for dealing with residents of the neighborhoods in Jerusalem’s municipal jurisdiction located outside the fence.

- Regulation of open-air markets near the crossings.

- Enforcement of public order in the vicinity of the crossings by a municipal inspection unit.

- Establishment of municipal service centers close to the crossings in the framework of services provided by the state.

- Ministry of Defense in coordination with the Ministry of Public Security

- In cooperation with the Ministry of Transport, regulation of pedestrian and vehicular traffic of the residents and authorized public transportation that will facilitate passage in both direction within a reasonable time.

- Establishment of alternative traffic routes for residents under various scenarios at the crossings (sabotage, traffic accidents, etc.).

- Construction of infrastructure to enable government ministries to provide services at the crossings.

- Jerusalem municipality in cooperation with the Ministry of Education, Culture, and Sport

Inside the Fence:

- Organization of a system for regular and supervised transportation of students to schools within Jerusalem in preparation for the 2005-2006 school year.

- Renting classrooms, adapting them to the safety requirements, and equipping them to accept additional students in preparation for the 2005-2006 school year.

- Construction of educational institutions in order to reduce rental and transportation expenses in the long term.

Outside the Fence:

- Renting classrooms according to the existing mapping in preparation for the 2005-2006 school year.

- Operating a second shift in a number of schools to compensate for the lack of buildings available for rent in preparation for the 2005-2006 school year.

- Construction of new educational institutions in order to eliminate the second shift in the long term.

- Ministry of Health

- In coordination with the relevant parties – setting passage procedures that will facilitate providing rapid and humane service for those in need.

- In coordination with the relevant parties – setting passage procedures that will make it easier for doctors and equipment to go outside the fence from inside it.

- Encouragement of hospitals in eastern Jerusalem to open branches beyond the fence.

- Encouragement of health funds to expand their activity beyond the fence.

- In coordination with the relevant parties – issuing regular authorization to medical teams to enable them to pass through the crossings quickly.

- Ministry of Communications – Postal Authority

- Establishment of postal units close to the crossings.

- Providing services from government ministries through the postal branches, as currently practiced, and extending this service in the framework of the law, subject to negotiations between the Postal Authority and the various agencies.

- Establishing postal distribution centers outside the barrier.

- Ministry of Welfare and Social Services – National Insurance Institute

- Activity at the crossings utilizing both human and computerized response.

- Providing services through the Internet.

- Providing services by telephone.

- Providing services through the Postal Authority.

- Ministry of Transport

- Giving priority in passing through the crossings to vehicles used in authorized public transportation in the following ways:

- Preparing access lanes for public transportation before the crossings.

- Exclusive traffic lanes.

- Preparing a special lane at the crossings for passengers on public transportation, together with a lane for ordinary vehicles.

- Preparing terminals and stations at a crossing for passengers switching vehicles on the way to destinations in Judea and Samaria and back.

- Establishment of a station for providing services from the Israel Department of Motor Vehicles.

- Providing services through the Postal Authority.

- Ministry of the Interior

- Services that do not require identification will be provided through the Postal Authority.

- Establishment of a branch of the Ministry of the Interior at the crossings for providing services that require identification.

- Ministry of Industry, Trade, and Labor – An employment service.

- Setting the frequency of attendance for residents outside the barrier at once a month.

- Maintaining regular office hours at branches to be opened at the crossings.

- To add NIS 17 million to the Ministry of Public Security’s 2005 budget and a one-time NIS 8 million payment to the Jerusalem municipality’s budget, including NIS 3 million for education, for municipal and other actions described in Section 2 above. The budget for completing preparations and providing public services from 2006 onwards will be determined in discussions between the Ministry of Finance and the Ministry of Public Security; the Ministry of Education, Culture, and Sport; the Ministry of the Interior; and the Jerusalem municipality as part of the discussions for the 2006 budget, while taking note of the Jerusalem municipality’s need to immediately commit to renting buildings and to sign long-term contracts with transportation providers. The discussions between the Ministry of Finance and the Ministry of Education, Culture, and Sport, with participation from the Jerusalem municipality, will be completed by end of July 2005.

- To instruct the parties involved to complete their staff work on the Jerusalem security fence pertaining to the tourism sector and passage of VIPs, including Christian clergy for religious rituals.

- To authorize the acting Prime Minister; the Minister of Industry, Trade, and Labor; and the chairman of the inter-ministerial committee of directors general appointed by the Prime Minister to plan assessments of, follow up, and monitor the ministries’ preparations under the above decision. The security agencies will “close” the barrier only after receiving a recommendation from the acting Prime Minister and the Minister of Industry, Trade, and Labor that the requirements of ordinary life have been supplied.

[1] Mati Steinberg, “The Chaos Program according to Al Qaeda,” from Hakeshet Hahadasha (The New Arc), pp. 12-14, 2005.

photo: Source: Jerusalem municipality.

- בניית אתרים

- בניית אתרים