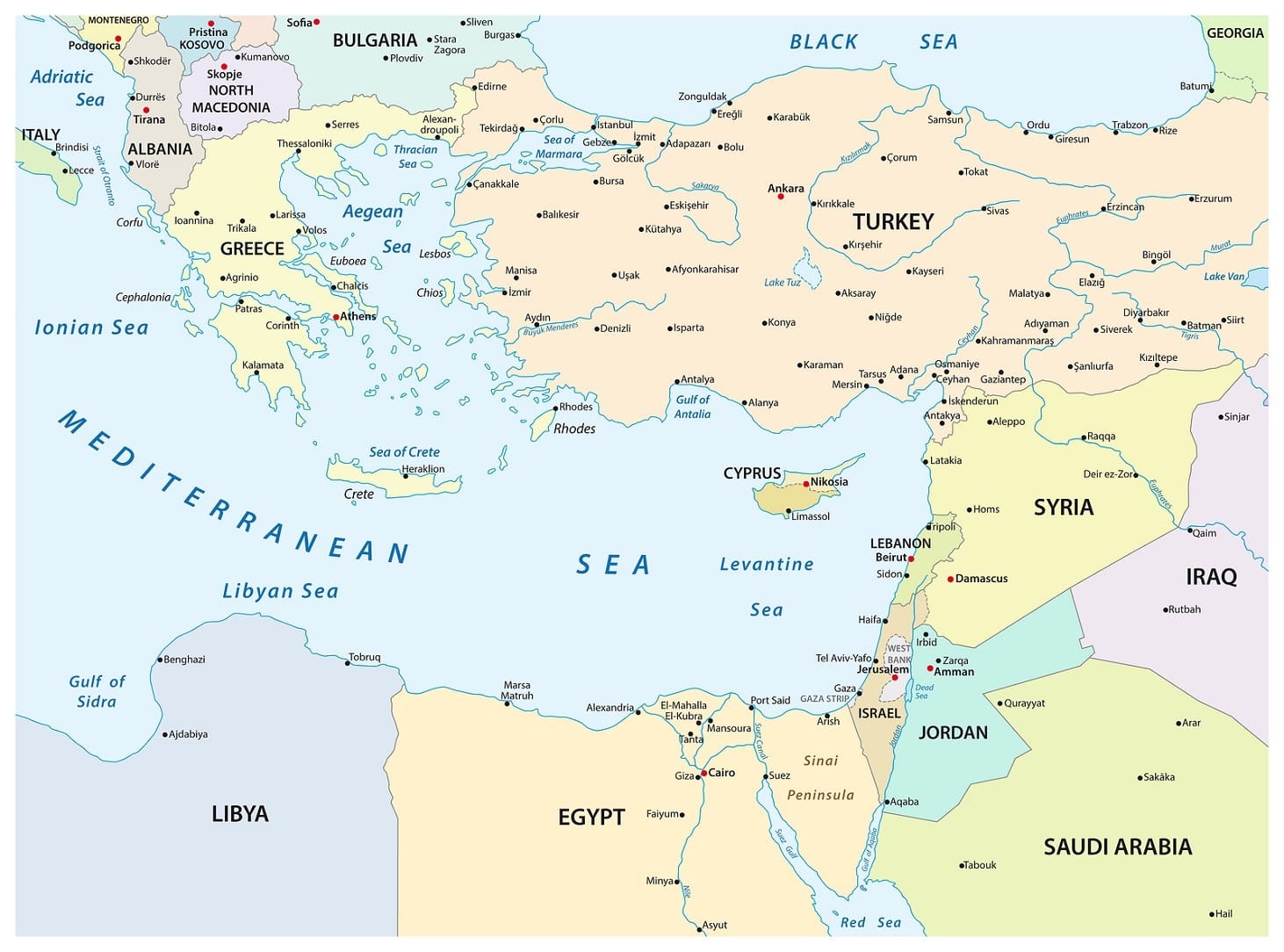

Israel, Egypt, Greece and Cyprus must encourage the US to assert a higher military and diplomatic profile as a counterweight to Turkish pressures, Russian and Iranian ambitions, and Chinese inroads.

For the second time this year, energy ministers from Israel, Italy, Egypt, Greece, Cyprus and the Palestinian Authority (and a lower-rank Jordanian representative) met in Cairo on July 25 as members of the Eastern Mediterranean Gas Forum (EMGF). They were joined, significantly, by US Secretary of Energy Rick Perry, as well as by European Union Commissioner for Energy Miguel Arias Canete and representatives from France and the World Bank. This indicates that the emerging alignment of forces in the Mediterranean is a recognized strategic development.

As commentator Ahmad Kotb recently wrote in al-Ahram (July 31), this is and should be about “more than just gas.” (This is a significant statement coming from an Egyptian, given Israel’s overt contribution to the EMGF, and the traditional Egyptian reluctance to allow such a role).

The American and international recognition was already implied when US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo took part in the Greek-Cypriot-Israeli tripartite summit in Jerusalem in March 2019. There is now an opportunity for EMGF participants, and particularly Israel, Greece (under a new, openly pro-Western government), Cyprus and Egypt, to actively broaden the scope of their cooperation. As has been previously suggested, the “3+3” (and the PA) can emulate the semi-formal structure of the 5+5 in the Western Mediterranean and create a broad-based consultative forum operating at several levels, from leaders to professionals and officials.

While joint strategies for the most effective exploitation of energy resources in the eastern Mediterranean is a vital part of EMGF’s purpose, there are other fields of action that need to be explored. Based on Pompeo’s and Perry’s engagement with the eastern Mediterranean alignment, the US should be encouraged by all like-minded players in the region to enhance its presence, both in military and diplomatic terms. (It has been a while since a carrier task force deployed to the eastern Mediterranean).

This should serve to curb the ambitions of Russia to turn its grip on Syria into a permanent strategic presence in the region. It is equally important as a signal to President Erdogan in Turkey that violent intimidation (specifically, towards Cyprus) may be counterproductive. It can also be of help in limiting the impact of Chinese inroads in the Mediterranean.

This requires some elaboration. There can be some benign explanations for the Chinese effort to develop and even possess ports in the region. Financially, Chinese sovereign funds are huge (measured in trillions of dollars), and constantly seek new projects in which to invest. In straightforward commercial terms, points of entry in southeastern Europe such as Trieste and Piraeus can greatly reduce the cost of trading, particularly with markets in the central and eastern European hinterland that until now were served by shipping around Africa to Rotterdam or Hamburg.

For Chinese industries, constantly growing and absorbing millions of new internal migrants every year, expanding existing markets and entering new ones is a vital need. With the internal boom in construction dying off, Chinese steel industries are looking for things to build abroad. As the Greek case proves, state of the art Chinese technologies in basics such as container transport can transform old, neglected ports into modern economic hubs, generating benefits for all concerned.

At the same time, this is indeed part of a broader and potentially problematic Chinese strategic design; and as such, needs to be dealt with in the context of the global balance of power.

It is no longer possible to ignore the growing sense of concern, frustration and even anger in Washington in the face of the rising tide of Chinese investment, and in some cases control, of key facilities in Israel. Israel has been put on notice on this matter again and again, most recently by Secretary Perry. Increasingly, the perception in Washington is that of a zero-sum game in which any gain for China is almost by necessity a loss for the US. To this should be added the very real suspicion that the PRC military uses the cover of any large-scale Chinese corporate presence for intelligence-gathering and cyber penetration.

Ultimately, if indeed forced to choose, Israel must remain loyal to its alliance with the US, which is rooted in interests, values, and Jewish peoplehood. Israel should work in conjunction with others in the region to withstand Chinese pressures and temptations.

Regional friends and allies should also work together to prevent any enhancement of Iran’s presence in the eastern Mediterranean, beyond the already dangerous stranglehold that Hizbullah has on Lebanon. In their remarkably close dialogue with Russia, both Israel and Egypt should take the initiative to persuade President Putin that it is not in his country’s best interest to allow Syrian soil and Syrian ports to become Iranian bases.

Meanwhile, EMGF European participants, Italy, Greece and Cyprus (members of the EU), can join hands in inducing a more sober look in Brussels at the dangerous realities of the region. Europe must recognize the urgent need to shore up Egypt, Jordan, and others in the Mediterranean basin (including Morocco in the west) committed to the fight against the forces of subversion and destabilization.

More can be added to this list. The joint naval exercise in Haifa in early August 2019 – in which ten nations participated alongside the Israeli navy, including French and Greek ships – simulated a response to a major earthquake. This served as a reminder that natural or man-made emergencies would necessarily require a common Mediterranean response. (This indeed happened during the wildfires in Israel in May 2019, and on previous occasions). The same can be said about the effort to prevent the use of “our sea,” the Romans’ Mare Nostrum, for drug smuggling and human trafficking. In these respects, closer coordination with NATO’s Mediterranean headquarters would benefit all EMGF participants.

Ultimately, in addition to the practical considerations listed above, the emergence of this alignment (– not quite yet an “alliance”) also can serve the higher purpose of proving that the Mediterranean can and should be a bridge, not a moat; uniting, rather than separating nations. This includes Egypt (Muslim by faith), Christian countries (both Catholic and Orthodox), and Israel (a Jewish state). They can complement one other, and together contributing to regional and international stability. As President ‘Abd al-Fattah al-Sisi suggested in 2015, EMGF counties can offer a vitally needed alternative to the false and deadly ideology of totalitarian Islamism.

JISS Policy Papers are published through the generosity of the Greg Rosshandler Family.

photo: Bigstock

- בניית אתרים

- בניית אתרים