Iraq is ripe for a nationalist, public-service driven politics where good governance is more important than identity. If Iraqi leaders, with US support, can move the country in a new direction, Iran’s ability to take advantage of Iraqi state weakness to threaten Israel will be drastically curtailed.

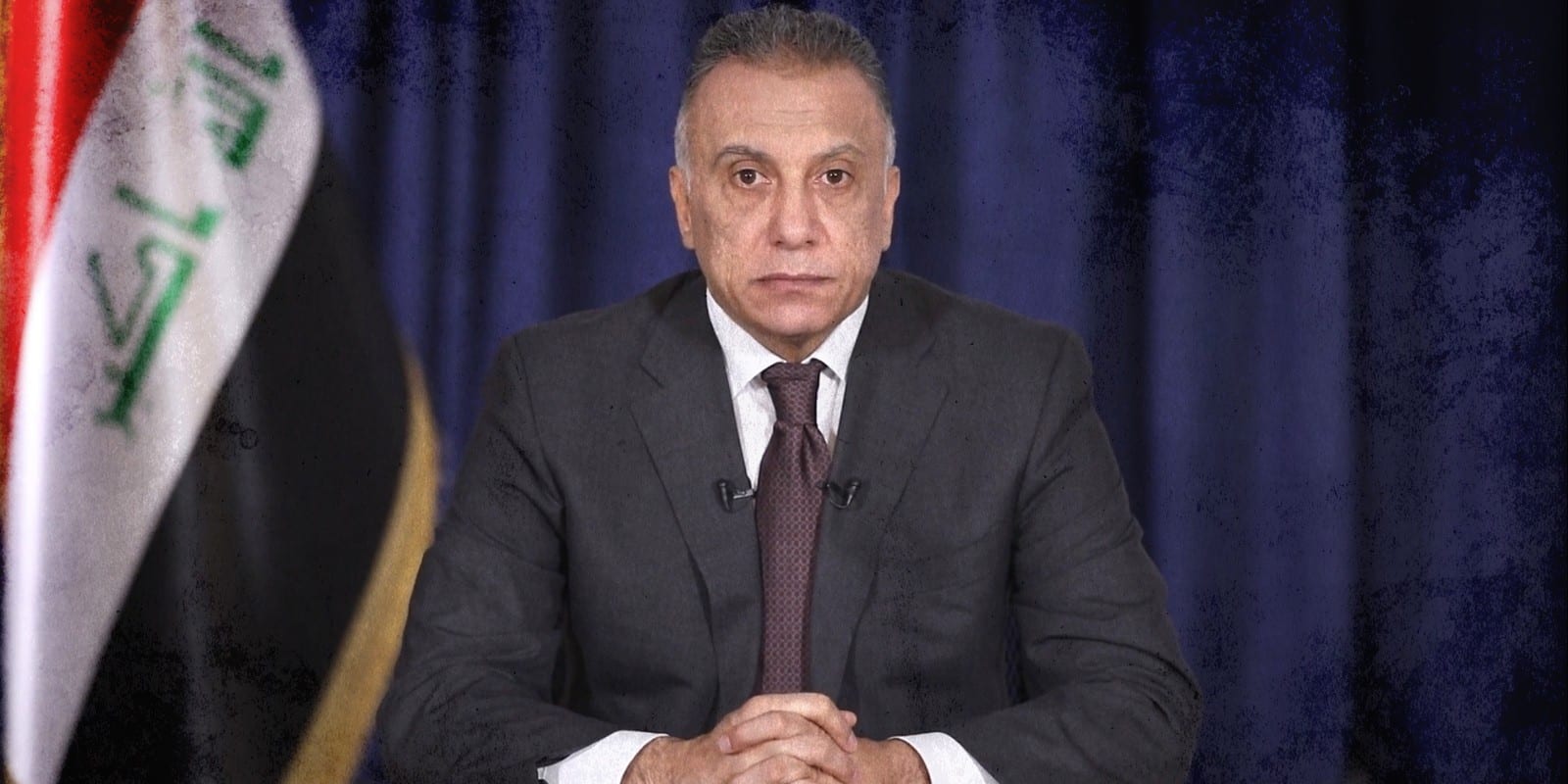

On June 11, American and Iraqi officials kicked off the much-anticipated Strategic Dialogue between the countries with a two-hour virtual meeting. The talks, slated to continue in-person at some point this summer, seek to determine the state of the US-Iraqi relationship for the foreseeable future. They take place as Iraq faces intense security, political, economic, and governance challenges. The deep problems facing the country are interconnected, and American support is vital to new Iraqi Prime Minister Mustafa al-Kadhimi’s ability to create a functioning, coherent country that prioritizes the needs of its citizens.

The outcome of the talks – and indeed the bilateral relationship itself – has implications beyond Iraq’s borders. Neighbors like Iran, Turkey, and the Gulf states have a significant stake in its outcome. But they are not the only interested parties. Israel should not fool itself- the potential for developments in Iraq to affect Israeli security is growing, and decision-makers should be following the strategic dialogue closely. If Iraqi leaders, with US support, can move the country in a new direction, Iran’s ability to take advantage of Iraqi state weakness to threaten Israel will be drastically curtailed.

Though the challenges are daunting, there is reason for cautious optimism that Iraqis can address some of the deep-seated issues afflicting the country.

Strategic Framework Agreement

In December 2008, the US George W. Bush Administration and Iraq’s Nouri al-Maliki government signed two watershed agreements, the Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA) and the Strategic Framework Agreement (SFA). Under SOFA, US forces had to leave Iraqi cities by June 2009 and withdraw from the country entirely by December 2011. Under President Barack Obama, US forces returned to Iraq in 2014 to lead the coalition against the Islamic State. There are over 5,000 US troops in Iraq currently.

The SFA establishes the framework for determining the long-term relationship between the two countries in the economic, diplomatic, cultural, and security fields. It includes broad commitment by the US to “support and strengthen Iraq’s democracy and its democratic institutions…and in so doing, enhance Iraq’s capability to protect these institutions against all internal and external threats,” and “enhance the ability of the Republic of Iraq to deter all threats against its sovereignty, security, and territorial integrity” by fostering close cooperation on defense and security matters.

In addition, it calls for a “Higher Coordinating Committee” to oversee the progress of the agreement, develop specific goals, and meet periodically. The current Strategic Dialogue is part of those periodic talks and is the most important set of talks under the SFA in the past decade.

Though to this point the talks have been at the undersecretary level, they still have the potential to recalibrate the relationship and to accomplish some goals like enhancing the Iraqi states ability to limit Iranian influence and to create some semblance of governance in the country. But it is no secret that Iraq faces substantial challenges in every subject covered by the talks – governance, corruption, economy, and security.[1]

Iraqi governance is a mess, and the political system and culture that emerged in the post-US occupation period are not currently equipped to meet the needs of its people. The sectarian character of Iraqi politics has created a reality in which lawmakers seek to stave off descent back into violence through uneasy truces between Shiites, Sunnis, and Kurds. There is little capacity to focus efforts on addressing housing, jobs, inflation, and other daily concerns of the citizenry.

Corruption is endemic in the country, with an elite that lives off the country’s oil wealth. Former prime minister Nouri al-Maliki created a patronage network of supplicants throughout key security and economic ministries. Ongoing attempts at creating a technocratic government show a desire to move away from the Maliki era.

However, it will be far more difficult to offer effective governance with an economy in shambles. The twin shocks of drops in global oil prices and the COVD-19 pandemic pushed the Iraqi economy to the brink of collapse. Oil is the only significant export, which maintains the bloated public sector and lines the pockets of the political class, while leaving much of the public out of work and hungry.

Massive grassroots protests erupted in October 2019 to protest these conditions, the government, and interference in Iraqi affairs by outside – that is, Iranian – actors. Shiite militias loyal to Iran, as well as their Sadrist counterparts, broke up the protests violently, killing hundreds.

The US can help Iraq deal with these challenges. According to the official statement issued following the June meeting, “The United States discussed providing economic advisors to work directly with the Government of Iraq to help advance international support for Iraq’s reform efforts, including from the international financial institutions in connection covered US and international support for the next round of Iraqi elections and strengthening the rule of law and human rights.”

American economic support – especially in cooperation with the IMF and World Bank that incentivizes greater transparency and responsible privatization of state monopolies – will help real Iraqi reformers take steps toward more representative and localized governance.[2]But international aid will be in short supply in the global recession in the wake of the coronavirus. If Iraq is to put itself in the running for the type of loans it needs, it will have to address “to fiscal controls and management, meeting cost and time schedules, and producing effective results.”[3]

The US can also continue its pressure on Iran within Iraq, and help reduce Tehran’s economic and political control in the country. As long as Iran and its PMU proxies hold sway over Iraq’s economy and political institutions, government policies will not align with the interests of the Iraqi public.

Ongoing sectarianism will render all of Iraq’s woes unsolvable. It will take years to undo the local and national structures that emerged around from zero-sum sectarian competition. The US has proven capable of bringing rivals to the negotiating table in Iraq. It will create a far improved environment for tackling economic and political problems if it focuses on reconciliation and helping Iraq move beyond narrow sectarianism. Of course, the less Iranian influence there is, the easier this task will be.

The Security Challenge

The final challenge, and the one that is most relevant for Israel, is security. Since the Trump Administration pulled out of the JCPOA nuclear deal and initiated its maximum pressure campaign against Iran, Iraq has become an arena for Washington and Tehran to fight it out. Tensions escalated drastically in December 2019, with American strikes on the pro-Iranian militia Kata’ib Hezbollah (KH) forces in Iraq and Syria, and the attempted storming of the US Embassy in Baghdad. In response, Trump ordered a targeted strike on IRGC-QF commander Qassem Soleimani, killing him and KH commander Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis. On January 8, Iran struck bases in Iraq housing US soldiers with ballistic missiles. The violence continued into March, with a deadly missile attack on Coalition forces in Taji, and US strikes on PMU forces and weapons facilities.

ISIS is also becoming a pressing security issue once again. Though the Iraqi government declared victory over the organization in 2017, and ISIS is still unable to hold territory, attacks rose after the killing of leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdad in October 2019. ISIS has focused on Diyala, Kirkuk, and Salahadin provinces, transferring fighters from Syria to take advantage of the focus on the coronavirus, lack of coordination between Kurdish, PMU, and Iraqi forces, and a reduced American presence in the area as a result of Iran-backed attacks.[4]

To deal with this threat, and with pressure from its neighbors, Iraq needs a capable national security force. The Iraqi Security Forces (ISF) must be able to carry out counterterrorism operations and to deter other countries who seek to meddle in Iraqi affairs. It must be a truly national force that does not serve sectarian agendas or maintain loyalty to political parties. This means building on the few capable units that currently exist, replacing outdated equipment, developing its small air force, and improving its self-sufficiency.

Shiite militias loyal to Iran, like Badr, KH, al-Nujaba and Asaib Ahl al-Haq, are a major obstacle to the creation of a capable ISF. These organizations are loyal to the Islamic Republic of Iran and serve its interests. They attack US forces at Iran’s behest to drive them out of the country and reduce Western influence. PMU forces have also targeted Iraqi troops. They played a key role in violently suppressing public demonstrations by using lethal force against Iraqi civilians.

The US has much to offer Iraq in terms of security. Iraq’s border with Syria continues to be porous south of the Kurdistan Region. Improving border security is crucial to limiting ISIS’s ability to travel between the countries and carry out attacks. The US, Interpol, and other international partners have helped Iraq identify terrorists through biometric-information sharing. Providing technological solutions to Iraqi manpower shortages at the border is only one way that the US can help Iraq improve its security.

In July, US Task Force-Iraq, which led the international anti-ISIS coalition, officially transitioned to the Military Advisor Group (MAG), reducing personnel and reorganizing to focus on the next phase of its advisory role. According to an official US military statement, “Coalition advisor teams will provide specialized planning mentorship to ISF directorates overseeing operations, logistics, intelligence and other military functions. The MAG will include a Joint Operational Command Advisor Team and two Operational Command Advisor Teams. All elements will assist the ISF with operational planning, intelligence fusion, and air support for Iraqi-led military operations to defeat the Daesh threat in Iraq.”[5] It is crucial that the ISF enhance its own counterterrorism capabilities so that it can fulfill its missions without relying on PMU forces loyal to Iran. The US and Iraq will have to define the future role of US forces in the country, and how they will be protected from Iranian-backed attacks.

It is in America’s and Iraq’s interest that US forces maintain some presence in the country, in full agreement with Baghdad, to limit Iranian influence. Not surprisingly, Iran and its PMU allies have been vocal about their demands that America leave the country. The only public support for a continued American presence is heard, not surprisingly, in the Kurdistan Region, though almost all Sunni politicians boycotted the January 5 parliamentary session that voted to expel US troops. And Kadhimi enjoys the support of the majority of Iraqis and the majority of Shia at this stage.[6] Moreover, given Iran’s vulnerability, it is unlikely that Tehran will be able to significantly influence Iraq’s position on the presence of US troops in the ongoing strategic dialogue.

Furthermore, if Kadhimi over the next 18 months is able to lead a government that addresses the needs of the Iraqi people, the public will continue to turn away from the sectarian violence of the last decade and from Iranian influence. A functioning Iraq that prioritizes governance and development will have no incentive to involve itself in Iran’s efforts to harm Israel.

Israel’s Interest in the Strategic Dialogue

In the past, the strength of the Iraqi state dictated the scope of the threat it posed to Israel. When Iraq was powerful, it could send significant expeditionary forces to Israel’s border to participate in Arab-Israeli wars, as it did in 1948, 1967, and 1973. Israel tried unsuccessfully to forestall Iraqi expeditions by supporting the Kurdish rebellion in Iraq’s Kurdistan region, seeking to undermine the internal unity of the Iraqi state.

Today, however, the situation has changed. The coherence of the Iraqi state benefits Israeli security, while its weakness allows Iran to turn it into another territory in the crescent stretching from Iran to the Lebanon from which it seeks to threaten Israel.

Iran has several means of harming Israeli security from Iraq. The PMU is the primary tool. There are several ways in which the PMU could threaten Israel from Iraq, some of which Israeli has already begun responding to. The most obvious is the transfer of precision missiles from Iran to Syria through Iraq. Israel sees Iran’s campaign to improve the precision capabilities of Hezbollah as crossing a red line, and Israel has proven willing to take military action to disrupt this effort. For years, it has struck weapons convoys and depots in Syria, and it has started to do so in Iraq.

Iran-backed proxies could also use western Iraq to fire rockets and missiles at Israel. Because of the distance and reduced intelligence coverage, it would be harder to Israel to combat rocket launches from Iraq than from Syria or Lebanon.

Iraq could also pose a threat to Israeli pilots. Providing the PMU and/or the Iraqi military with advanced air defense capabilities would make it even more dangerous for the IAF to operate over Iraq and Syria. Reducing Israel’s ability to safely fly over Iraq disrupts intelligence-gatherings efforts, allowing Iran to develop infrastructure and transfer missiles more safely. In addition, Israel’s freedom of action in striking Iranian convoys and proxies, or potentially nuclear installations, would be limited.

Conclusion

The strategic dialogue with the US comes at a possible turning point for Iraq. The country is ripe for a nationalist, public-service driven politics where good governance is more important than identity. If Kadhimi can start meeting this demand in the short time he has before early elections, and the US maintains its influence in Iraq, the country has a chance to become a coherent state that can fend off Iranian attempts to use it for its own interests.

Israel is not in a position to influence the American-Iraqi talks, nor should it try to do so. Change in Iraq will come as a result of Iraqi leaders meeting the demands of wide segments of the Iraqi public, with American support. This is the outcome that Israel should hope for, and it should pay close attention to the talks over the coming months.

[1] Anthony Cordesman, “Strategic Dialogue: Shaping a U.S. Strategy for the ‘Ghosts’ of Iraq,” CSIS, June 8, 2020.

[2] Cordesman, “Strategic Dialogue,” CSIS, 36.

[3] Cordesman, “Strategic Dialogue,” CSIS,59.

[4] Farnaz Fassihi, “Iran Sees New Surge in Virus Cases After Reopening Country,” The New York Times, May 18, 2020.

[5] “Coalition Task Force-Iraq transitions to Military Advisor Group,” July 4, 2020. https://www.inherentresolve.mil/Releases/News-Releases/Article/2250749/coalition-task-force-iraq-transitions-to-military-advisor-group/

[6] Munqith Dagher, “Iraqi Popular Opinion of Kadhimi is Weakly Supportive, but Could Tip Either Way,” The Washington Institute, July 15, 2020. https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/fikraforum/view/Iraqi-Public-Opinion-Polls-Kadhimi-Government-Iraq-Shia

Photo: The Media Office of the Prime Minister of Iraq

- בניית אתרים

- בניית אתרים