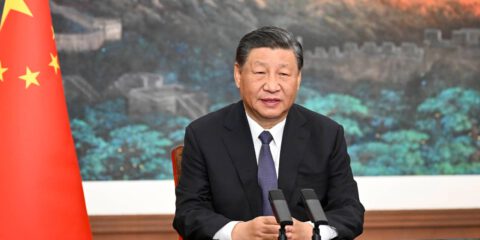

China aims to play a more proactive role in the Middle East, maintaining cordial relations with all rival countries. Beijing attaches great importance to its ties with Saudi Arabia, the Emirates and Egypt, and therefore has welcomed the Abraham Accords (albeit in lukewarm fashion, because of tensions with the Trump administration).

A decade ago, the Arab Spring severely compromised Chinese investment in the Middle East and jeopardized tens of thousands of Chinese nationals throughout the region. As “spring” turned into “winter,” Beijing watched a wave of civil unrest consume the region. Fearing similar challenges to stability at home, China’s policymakers have reopened the question of China’s role in the Middle East.

While most Chinese leaders agree that China should enhance its presence in the region, there is no consensus on the course and scope of action. Furthermore, there is a discrepancy between the general acrimony between China and the US, and the recognition that it would be counter-productive to challenge a relatively balanced status quo in the region under US hegemony. Economic interests, which demand peace on one hand, and geopolitical concerns on the other hand, pose a dilemma for China.

A recent example is the Chinese response to the Abraham Accords (– the normalization of relations between Israel, the UAE and Bahrain, as signed at the White House on September 15). Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Zhao Lijian described the normalization in August as a welcome step towards fostering regional peace and stability. Following the positive line were Mideast scholars such as Fan Hongda, who wrote that “after years of tribulation, the people’s desire for peace in the Middle East is far greater than that of their peers in stable regions … Indeed, Middle Eastern leaders who depend on confrontational rhetoric are increasingly losing their base.” (This is an uncommon critique of Iran and the Palestinian Authority).

Fan Hongda argues that the normalization “should be given more support and recognition, as this is objective demand and an unavoidable trend in the development of the Middle East.” On the Palestinian issue, Fan said that “times have changed.” Placing a settlement of Palestinian grievances as a prerequisite for peace “is no longer in line with the realities of the Middle East, and “in light of developments over the last two decades, there is no choice but to accept that peace between Palestine and Israel has reached a dead end” (Fan, 2020).

After several years in which the Chinese media have been quick to criticize the Trump administration’s actions in the Middle East in general, and its peace plan in particular, and in a time of great friction between the White House and Zhongnanhai, it was unexpected to see favorable reactions to the American initiative. Even critics have acknowledged that normalization is an inexorable trend and that the Palestinian issue is no longer the central conflict in the Middle East. The Iranian issue has taken its place.

Other scholars and diplomats, such as former Chinese Ambassador to Iran Hua Liming, also welcomed the move. “After all, reconciliation between the Arab states and Israel is also one of China’s diplomatic ambitions in the Middle East.” However, diplomats qualified their enthusiasm because they consider these developments a veiled attempt by the US to consolidate an anti-Iranian alliance. This, in turn, could further destabilize the region, so much so that it may even lead the rival factions into a “new Cold War.” Some noted that the Gulf states and Israel have no real basis for cooperation other than competition with Iran and Turkey, and that the US is violating the rights and interests of the Palestinians for political gains.

What initially seemed like a paradigm shift in the way that Chinese policymakers and media have expressed themselves regarding the Mideast has gradually evolved into another opportunity to sling mud at the US. For example, the Middle East scholar Jin Liangxiang of the Shanghai Institutes for International Studies (SIIS) emphasized the normalization as detrimental to the Palestinian-Israeli peace process. In addition, Jin believes that normalization will drive a wedge between the Arab countries and undermine the forgotten Russian initiative of July 2019 to establish an international security mechanism in the Gulf region (which China immediately supported). In the long run, Jin wrote, the negative impact of the agreements will lead to uncertainty about the fate of Palestine as a sovereign state and regional stability (Jin, 2020).

A seminar on “New Trends in the Arab-Israeli Issue” was hosted on August 20 in Beijing by the Chinese Association for Middle Eastern Studies and the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS). It was attended by top scholars and diplomats, including Li Chengwen, Chinese Ambassador to the China-Arab Cooperation Forum (CASCF). The agenda indicates that the final topic dealt with the Chinese response to the developments in question. Although the contents of the discussions have not been released, it is fair to assume that they continued the ongoing debate among Chinese policymakers on China’s role in the Middle East.

On the one hand, China could continue to show support for normalization and even take a central part in it. Trump’s Vision for Peace is similar to the Chinese concept for conflict resolution of “peace through development” (– much more so than the democratization, market reforms and other liberal measures demanded by Trump’s predecessors as preconditions for peace). Like Beijing’s approach, Trump’s Peace to Prosperity plan promotes peace through the realization of economic potential, the development of infrastructure, the promotion of bottom-up ties between private sectors, fostering people-to-people connections and the strengthening of regional integration.

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the 2013 initiative most closely associated with Chinese foreign policy under Xi Jinping, also considers peace and stability as crucial to success. Some hope that developing countries and the Palestinians will be able to learn from the successful experience of the Chinese model of economic development and benefit from the resources of the second-largest economic superpower.

Chinese businesses would be able to benefit from the free trade and investment agreements that normalization facilitates. China may even undertake infrastructure projects that support regional economic integration, such as the now-shelved Red-Med project, a high-speed rail which would link Israeli ports along the Mediterranean and Red Seas. A freight train can transport goods to terminals in the port of Aqaba, Jordan, and from there across the region. While these measures could harm Chinese interests in Iran, evidence suggests that Chinese economic and political interests remain limited compared to those of GCC states (Garlick & Havlová, 2020).

Moreover, China needs a US military presence in the Gulf and Mideast more broadly to ensure that shipping lanes remain open, especially for oil exiting the Gulf. In addition, Sun Chengchao of the China Institute of Contemporary International Relations (CICIR) argues that China prefers that US naval forces be busy in the Mideast, which makes it more difficult for the US to divert forces to the Pacific theatre (Ling, 2020).

On the other hand, Chinese support for normalization may be ill-received by Iran, Turkey, and the Palestinians. (These forces are important to China for balancing American hegemony in the Middle East.) Turkey and Iran are backing Beijing in the international arena on topics such as the Uighur concentration camps in Xinjiang. This is especially true of Iran, which is a cheap source of energy. Iran’s relatively large and educated population and its location in the Persian Gulf and at the junction between Europe and Central Asia could make it an important geo-strategic junction for the Belt and Road Initiative and make it a lucrative investment arena.

In other words, the “Abraham Accords” is a Chinese catch-22. If China chooses to embrace the American vision it could damage its geopolitical interests, and if it rejects it, it could jeopardize the stability it needs for economic growth.

China is trying to grab the rope at both ends. It strives to remain friendly with all countries to sustain economic development and wants to project to its citizens and the international community an image of a proactive great power. Consequently, China will continue to challenge the US on international issues, such as the Palestinian question.

On controversial issues, China will pursue coalitions and multi-party agreements. For example, in a meeting between Foreign Minister Wang Yi and his Iranian counterpart Muhammad Zarif on October 11, Wang called for the formation of a new forum to ease regional tensions in which the member states would be bound by the Iran nuclear agreement (JCPOA).

By doing so, Wang reiterated one of the policy proposals contained outlined at the BRICS Forum at the beginning of September 2020. Another proposal called for the establishment of a forum for dialogue between Gulf states. While upholding the JCPOA, countries outside the region should “inject positive energy into the efforts to restore peace and stability in the region” – a statement which effectively ignores the Abraham Accords.

In lamenting that normalization polarizes the Middle East and exacerbates regional tensions, and by offering unreserved support for the JCPOA and the Palestinians, China is being unhelpful. Furthermore, Beijing’s moral support for Iran perpetuates the humanitarian crisis of the Iranian people and brings Tehran closer to a nuclear weapon.

Under the Trump administration, the US is doing its utmost to curb Chinese involvement in critical infrastructure in the Middle East. But even if it succeeds in rallying more countries to its cause, the US is unable to provide a competitive alternative to Beijing. China is Iran’s largest trading partner, oil importer and investor; the largest trading partner of the GCC as a whole; and the largest trading partner, individually, for Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Oman, and Kuwait. China is also Egypt’s top trading partner, and Israel’s second largest after the US. Approximately 3.5 million barrels of oil make their way to China from the Middle East every day, and it is assumed that a million Chinese nationals live and work in the region, with 300,000 in the UAE alone.

The list goes on, but the message is clear. China has too much invested in the MENA to pursue a policy of non-intervention. Beijing could use its resources to leverage growth, promote political restructuring, battle terror, and support deradicalization. This is the wish of its allies.

The next decade will be defined by the ongoing pandemic and great-power dynamics. Of all places, the conflict-ridden Middle East could become a focal point for Sino-American cooperation, and this is also in Israel’s interest.

References

Fan, H. (2020, September 13), cóng bālín yǐsèliè jiànjiāo kàn zhòngdōng hépíng zhī lù [The road to peace in the Middle East from the perspective of the newly established diplomatic relations between Bahrain and Israel]. Retrieved from Shanghai Observer: https://www.shobserver.com/news/detail?id=289626#top

Garlick, J. & Havlová, R. (2020), “The Dragon Dithers: Assessing the Cautious Implementation of China’s Belt and Road Initiative in Iran”, Eurasian Geography and Economics, doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15387216.2020.1822197

Jin, L. (2020, September 25), “The Trouble with Trump’s Middle East Moves”, Retrieved from China-US Focus: https://www.chinausfocus.com/peace-security/the-trouble-with-trumps-middle-east-moves

Ling, X. (2020, September 18), měiguó zài zhōngdōng de rúyì suànpán néng dǎ dé xiǎng ma? [Can America’s Wishful Thinking Work in the Middle East?]. Retrieved from Southern Daily: http://epaper.southcn.com/nfdaily/html/2020-09/18/content_7905126.htm

Zeng, J. (2019), “Narrating China’s Belt and Road Initiative”, Global Policy, 207–216, doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-5899.12662

Zhang, C. & Xiao, C. (2019), “China’s New Role in the Region of the Middle East: A Policy Debate”, Pacific Focus, 34(2), 256–283, doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/pafo.12140

JISS Policy Papers are published through the generosity of the Greg Rosshandler Family.

Photo: Freepik

- בניית אתרים

- בניית אתרים