When dealing with Europe, Israel can leverage its many technology and counter-terror assets, and it should demand diplomatic consistency and evenhandedness from the European Commission and from European governments. Israel should be cautious regarding Europe’s Eurosceptic governments and political parties.

Israel-Europe relations are beset by many paradoxes. On the one hand, the EU is Israel’s first trade partner, and Israel is an active participant in the EU’s research and development programs. On the other hand, those strong economic relations are often hampered by political disagreements over the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

On the one hand, Europe’s growing Muslim population nurtures the hostility of European politicians toward Israel. On the other hand, European governments hit by Islamic terrorism seek Israel’s expertise and cooperation.

On the one hand, Europe’s far-right and Eurosceptic political parties have anti-Semitic backgrounds. On the other hand, they are often Europe’s most pro-Israel voices.

This paper explains these contradictions and suggests policy recommendations for the future of Israeli foreign policy toward Europe.

****

Europe stood at the center of pre-statehood Zionist diplomacy, and it played a central role in Israel’s foreign policy after independence. It is among European leaders that Herzl sought support for the establishment of a Jewish state. It is a European country, Great Britain, that was granted by the League of Nations after WWI the mandate to establish a Jewish national home in Palestine. Israel fought its war of independence with weapons bought in Europe (from Czechoslovakia). After independence, Israel’s only military and diplomatic ally was European (France), and so was its main source of financial support (Germany, after the signature of the “reparations agreement”).

The end of the Franco-Israeli alliance in 1967 and the 1973 oil embargo soured Israel’s relations with Europe. By contrast, Britain’s policy toward Israel evolved from open hostility to discreet cooperation. The two former colonial powers set the tone of Europe’s policy toward Israel. With the establishment of the European Economic Community (EEC) in 1957 (and its replacement by the European Union, or EU, in 1992), Israel’s relations with Europe acquired a new dimension: Israel has both bilateral relations with member states and a multilateral relation with the EU.

Today’s European Union (EU) was preceded by the European Coal and Steal Community (ECSC, established in 1951) and by the European Economic Community (EEC, established in 1957). In 1964, the EEC and Israel signed a trade agreement that cut tariffs on Israeli exports. In May 1975, this trade agreement was significantly upgraded and expanded. The 1975 agreement established a free-trade zone for industrial products between the EEC and Israel; it cut by 85% European tariffs on Israeli agricultural exports; and it encouraged capital investments as well as cooperation in research and development.

The 1975 trade agreement was signed despite the fact that political relations between Israel and the EEC were strained by the oil embargo and by the EEC’s diplomatic statements on the Middle-East. During the 1973 Yom Kippur War, the nine governments of the European Economic Community (EEC) rejected an official US request to allow the American airlift en route to Israel to land on European territory. In the early 1970s, as US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger was trying to isolate the Soviet Union in the Middle-East, France maintained close ties with pro-Soviet Arab regimes: it built a nuclear reactor in Iraq, it did not prevent the Syrian invasion of Lebanon, and it promoted the PLO’s legitimacy in international fora. When the Camp David Accords were signed between Israel and Egypt in 1978, the French government criticized the agreements for not including the PLO.

Not content of giving a cold shoulder to the Camp David Accords, France convinced its partners from the European Economic Community (EEC) to adopt a common resolution calling upon Israel and the United States to add the PLO to future peace negotiations. The EEC eventually adopted such a resolution in Venice in 1980 (the “Venice Declaration”), which openly advocated the inclusion of the PLO in future negotiations. France was able to convince its EEC partners to sign the Venice Declaration thanks to the diplomatic effects of the oil embargo imposed by the Arab states after the 1973 Yom Kippur War. Before the 1973 oil embargo, European countries sympathetic to Israel (such as Holland and West Germany) were unwilling to add their voices to France’s Middle-East policies. After 1973, France’s Middle-East policy could count on the acquiescence and support of the EEC.

The 1975 trade agreement between the EEC and Israel was not upgraded for two decades. It took the 1993 Oslo Agreements for the European Union to update and upgrade, in 1995, the 1975 free trade agreement with Israel. Thanks to the 1995 agreement, Israel became the first non-European country to join the prestigious “Framework Programme” for research and development in 1996. Before the launching the “Fifth Framework Programme” in 1998, however, Israel’s membership had to be fought for due to political disagreements over the Middle East peace process.

In recent years between political disagreements between the EU and Israel affects economic cooperation. Since the Amsterdam Treaty of 1997 (which came into force in 1999) the EU has a High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy (whose powers and role were finalized with the Lisbon Treaty of 2009). Even though EU members still conduct their own foreign policies, and even though they are still divided on many foreign policy issues, they are at least trying to adopt a common policy on major international issues, and the High Representative is supposed to represent and defend that policy.

On the issue of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, the EU today speaks mostly in a unified voice, especially on the question of settlements for example. There is a very clear tendency today to make sure that the trade and scientific agreements between Israel and the EU do not apply beyond the armistice lines of 1949. In 2013, the “Horizon 2020” agreement on research and development between Israel and the EU was only signed after Israel agreed to exclude from the agreement Israeli companies that operate beyond the Green Line.

In November 2015, the European Commission instructed member states to label Israeli products manufactured or produced outside of the Green Line (those products can still be sold in Europe, but they cannot benefit from the EU-Israel trade agreement). With this policy, the EU denies a priori any change to the 1949 lines. Israel’s position, on the other hand, is UN Security Council 242 leaves room for flexibility, and that Israel’s future border with a prospective Palestinian state is a matter of negotiation. Moreover, the EU does not label products from other disputed territories such as Northern Cyprus or Western Sahara.

Another bone of contention between Israel and the EU is the fact that The European Commission and European governments donate millions of Euros every year to Israeli NGOs that influence Israel’s decision-making by petitioning the Israeli government at Israel’s High Court of Justice. Some of these NGOs are active in the BDS (Boycott, Divest, Sanction) campaign, others support the so-called Palestinian “right of return” -even though the EU officially opposes the boycott of Israel, and even though the “right of return” is incompatible with the two-state solution advocated by the EU.

In recent years, some have suggested that Israel should become a formal member of the EU. The prospect of a full Israeli membership is highly unlikely and possibly counter-productive. Israel is not a European country. Even if it were, full EU membership would hardly serve its interests. Indeed, not all European countries are EU members because they do not think that full membership would best serve their interests: Norway, Switzerland and Lichtenstein never joined, and Britain is in the process of quitting. These countries have their own association and trade agreements with the EU (as Israel does). As a small country, Israel’s influence would be completely diluted in EU decision making because of the voting system at the European Council.

Full EU membership also entails the predominance of European law over domestic law. In the case of Israel, laws related to Israel’s Jewishness (such as the law of return, or the status of religious courts in the realm of family law) might be deemed incompatible with EU law. There is also the issue of free movement of EU citizens among member states (within the Schengen Space). Add to this list Europe’s growing Muslim population and the radicalization of many European Muslims, and full Israeli membership becomes clearly unrealistic.

With Brexit, Israel will lose the rather pro-Israel voice (and votes) of Conservative British governments within the EU. On the other hand, if Britain were to be ruled by Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour Party, then Brexit would be in Israel’s interest (a Corbyn-led Britain would become a fiercely anti-Israel advocate within the EU). East European countries, which joined the EU between 2004 and 2007, have brought some balance to the EU’s attitude toward Israel. Recently, the Czech Republic, Romania and Hungary have blocked an EU decision that was meant to condemn the transfer of the US embassy to Jerusalem (the resolution was initiated by France). Indeed, both the Czech president and the Romanian prime minister have voice their support for transferring their country’s embassy to Jerusalem.

****

In recent years, Europe’s Middle-East interests have become more complex and multifaceted. For example, European politicians are influenced by growing Muslim constituencies, but European governments need Israel’s counter-terror expertise. Israel faces dilemmas too: Should it maintain its official boycott of Europe’s far-right parties or explore their pro-Israel credentials?

Israel can and should leverage its many assets: it is a technology powerhouse, a military and counter-terror expert, and an emerging natural gas exporter. Europe is a target of Islamic terrorism; it tries to diversify its natural gas imports; and its economic growth increasingly depends on technological innovation. The construction of a natural gas pipeline from Israel to Europe via Cyprus and Greece must be pursued. Israel can and should demand consistency and evenhandedness from the European Commission and from European governments. If they label products from disputed territories, they should apply this policy to all disputed territories (such as Northern Cyprus and Western Sahara) and not only to the West Bank. They cannot advocate a two-state solution and oppose boycott while funding NGOs that promote the “right of return” and BDS.

At the same time, Israel should be cautious regarding Europe’s Eurosceptic governments and political parties. Their pro-Russian foreign policy, protectionist economics, and illiberal attitude toward minorities are not in Israel’s interest. Russia supports Israel’s adversaries in the Middle-East; protectionist measures would hurt Israel’s trade with Europe; and European Jews are the first victims of legislation meant to outlaw religious practices such as circumcision and ritual animal slaughtering. While Eurosceptic and nationalist governments in Europe can be useful ad-hoc allies to offset hostile votes at the European Council and unwelcome initiatives from the European Commission, their agendas are not necessarily in tune with Israel’s interests.

JISS Policy Papers are published through the generosity of the Greg Rosshandler Family.

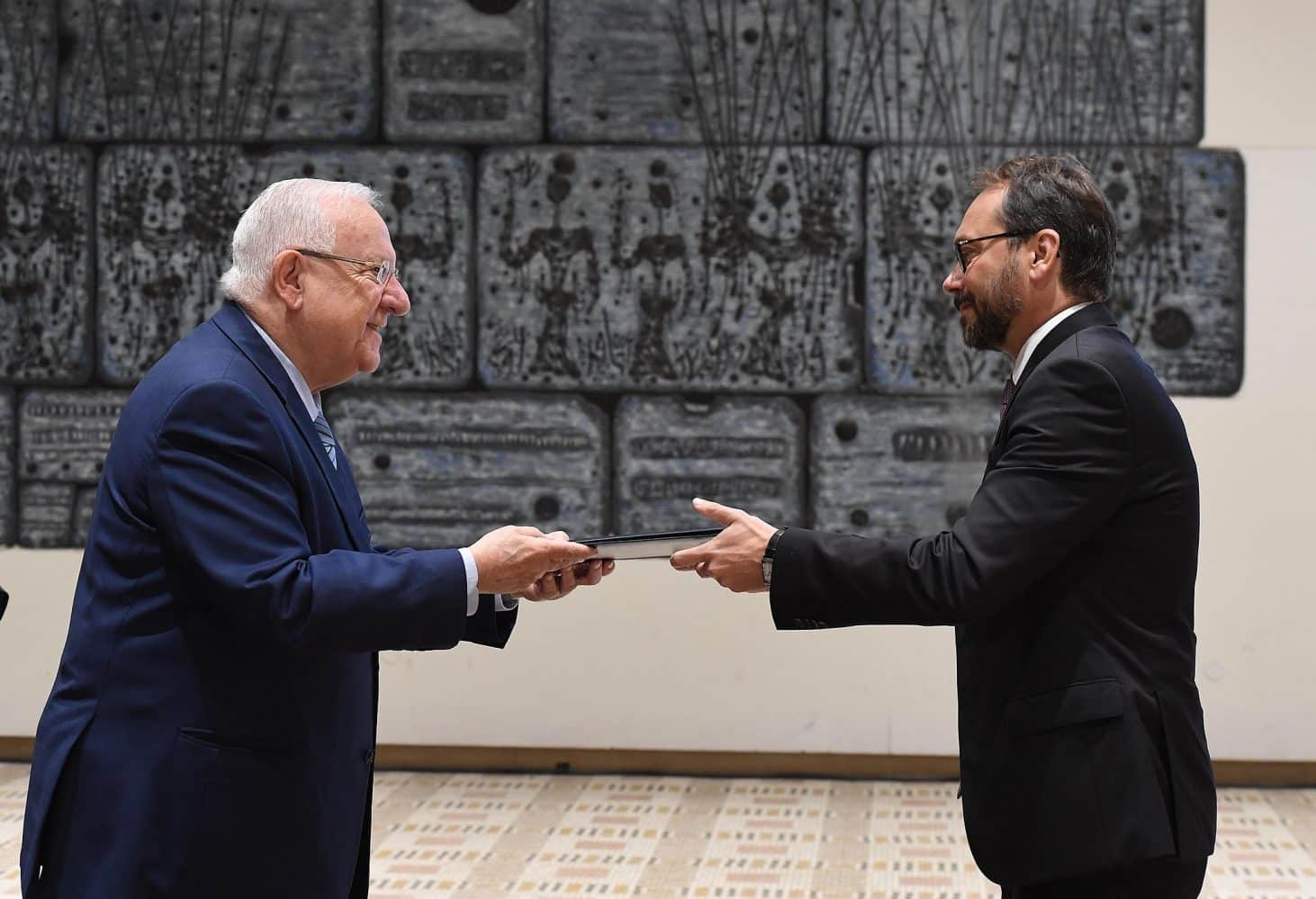

photo: Mark Neyman / Government Press Office (Israel) [CC BY-SA 3.0 ], via Wikimedia Commons

- בניית אתרים

- בניית אתרים