Despite the fascist roots of Matteo Salvini’s “Liga” party, upgrading relations with the current Italian government serves the national interest because it shall help Israel export it’s natural gas to Europe as well as break the European consensus on Iran and on Jerusalem’s status.

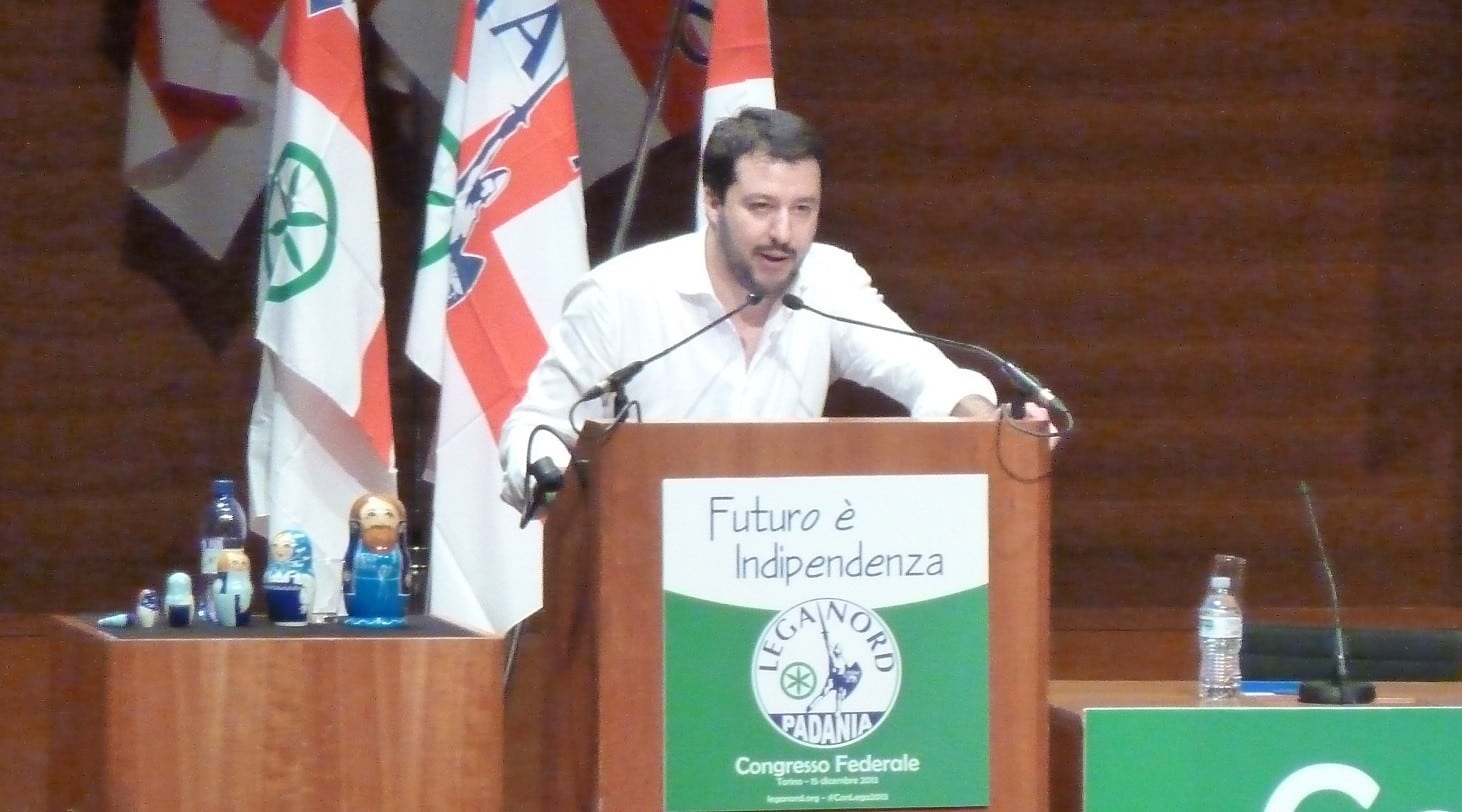

The visit of Italy’s Interior Minister Matteo Salvini to Israel has been criticized by those who accuse his “Lega” party of having fascist roots. The Ha’aretz newspaper ran an editorial asking the government to declare Salvini a “persona non grata.” President Reuven Rivlin’s office announced earlier this week that he would not be meeting with Salvini because of a busy schedule. This announcement was widely interpreted as a rebuke of Salvini, and it was praised as such by the Meretz party.

By contrast, I criticized President Rivlin over his decision on the ground that it was not coherent. If, I asked, human rights violations or affiliation with the populist right are good enough reasons for snubbing foreign leaders, then why did President Rivlin meet with Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban, with Austrian Chancellor Sebastian Kurtz (whose coalition includes the “Freedom Party”), and with Philippines’ President Rodrigo Duterte? President Trump has had much harsher words and deeds toward illegal immigrants than Matteo Salvini, yet boycotting the US President would not have even crossed Rivlin’s mind. Nor would Rivlin boycott Vladimir Putin despite the fact that he eliminates his opponents, expands his borders, safeguards Assad, and supports Europe’s populist parties (including Salvini’s).

Shortly after questioning Rivlin’s judgement in an op-ed, I was contacted by his spokesperson who explained that the President has no intention of boycotting Salvini and that the announcement on Rivlin’s busy schedule was genuine. So my accusation turned out to be unfounded. But the controversy around Salvini’s visit remains, and it provides an opportunity to assess Israel’s policy of rapprochement with Europe’s “populist” governments.

The controversy around Salvini is a typical foreign policy dilemma between Realpolitik and principles. The Israeli left, which is taking a strong stance against Salvini, has a peculiar way of addressing this dilemma. When, in June 2016, Benjamin Netanyahu signed a reconciliation agreement with Turkey (over the 2010 Mavi Marmara incident), Ha’aretz columnists (most notably Zvi Barel and Barak Ravid) praised Netanyahu for making the choice of political realism. The fact that Turkish President Recep Erdogan is an autocrat and an anti-Semite was not mentioned as an issue. Yet when it comes to Italy (a democracy and an EU member), the rules of Realpolitik no longer apply for some reason.

No country in the world would sacrifice its national interest for the sake of moral values. Expecting Israel (and only Israel) to do so is absurd. The question is not whether Israel is also entitled to play by the rules of Realpolitik (of course it is) but whether its policy of rapprochement with Europe’s “populist” governments serves the national interest. The answer is yes –though only to a point.

The 2008 financial crash and the 2011 ill-named “Arab Spring” plagued Europe with economic crisis, mass migration and ISIS-claimed terrorist attacks. Many Europeans have accused their elites and the European Union (EU) for the loss of jobs and of border controls. Hence the rise of governments that want to reclaim full sovereignty over economic and immigration policies in countries such as Poland, Hungary, Austria, Italy, and Greece. Hence the rise of parties such as Alternative for Germany or Marine Le Pen’s National Rally. And hence Brexit.

Those European governments and parties happen to admire Israel for what it represents: a proud nation-state that is both economically successful and socially conservative, and that has no qualms about defending its borders, about defeating terrorists, and about aggravating Eurocrats. Thanks to its strong ties with Europe’s “rebels” Israel has been able to break the Brussels consensus. Hungary, the Czech Republic and Romania, for example, have blocked an EU decision meant to condemn the transfer of the US embassy to Jerusalem. On the issue of Iran, the “Visegrad Group” (Czech Republic, Poland, Hungary, Slovakia) are making it harder for the European Commission to bypass the renewed US sanctions on Iran. Recently, Israel signed a memorandum of understanding with Cyprus, Greece and Italy to build a pipeline that will enable Israel to export its natural gas to Europe.

So Israel’s special ties with Europe’s “rebels” do serve the national interest, because they enable Israel to use “divide and rule” tactics in the EU on the issues of Jerusalem and Iran, and because they help Israel promote its natural gas exports to Europe despite the project’s many opponents (such as Spain, for example).

On the other hand, Israel has no interest in the dislocation of the EU and in the proliferation of “populist” governments, because these governments generally oppose free trade and are more inclined to align with Russia than with the United States. The EU is Israel’s first trade partner. Israel has a free-trade agreement with he EU and it is part of its flagship research and development program (“Horizon 2020”). Israel would therefore not benefit from a Europe dominated by pro-Russian mercantilists. But ad hoc and calculated links with the governments of Eastern Europe and of Italy do serve, for the time being, Israel’s national interest. Therefore, snubbing would Matteo Salvini (who happens to be the strongman of Italy’s government) makes no sense.

JISS Policy Papers are published through the generosity of the Greg Rosshandler Family.

photo: Fabio Visconti [CC BY-SA 3.0], from Wikimedia Commons

- בניית אתרים

- בניית אתרים