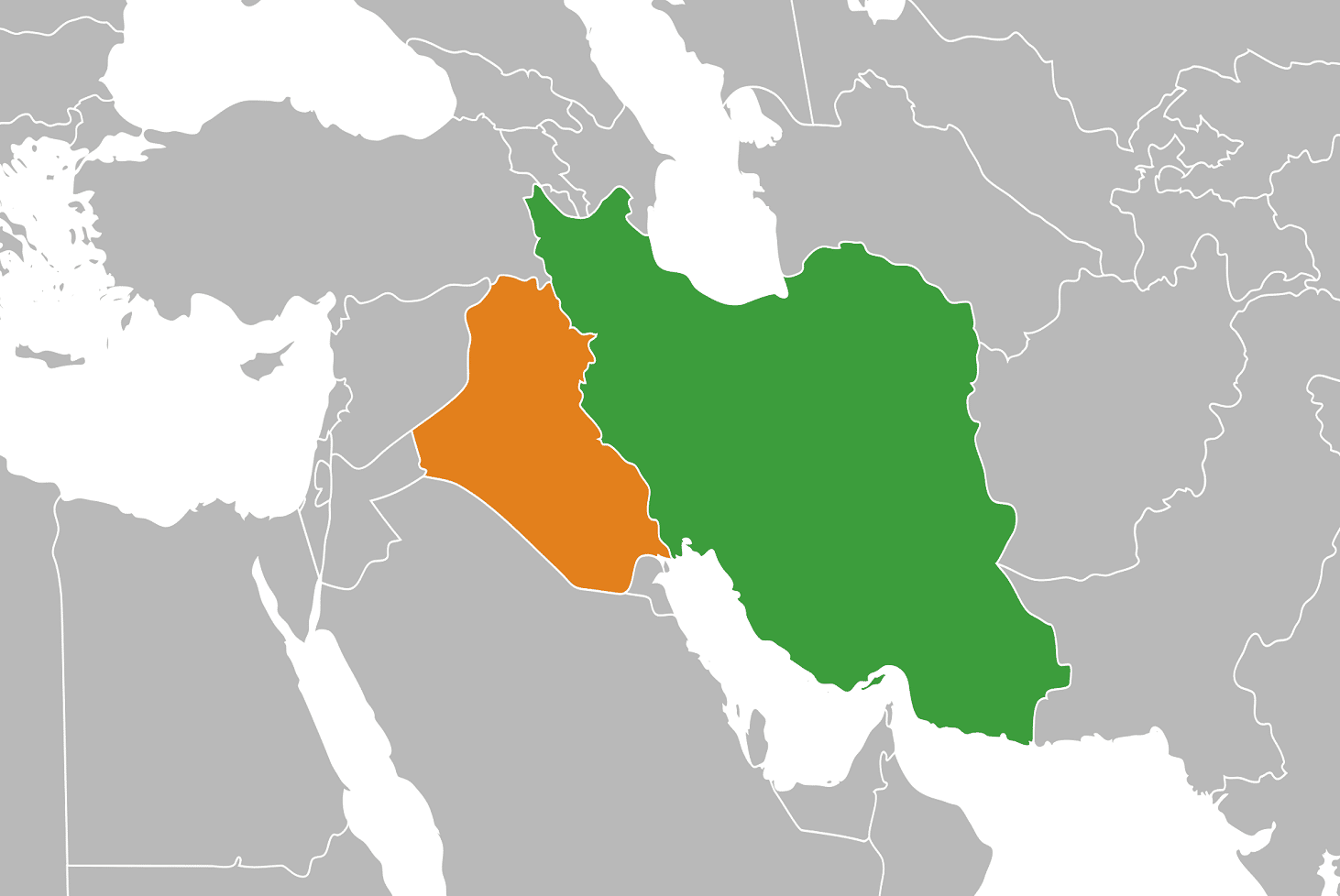

A key aspect of the ongoing political crisis in Iraq is the anger directed at foreign meddling, and specifically, at the role played by Iran and its proxies. The IRGC Qods Force has penetrated deep into Iraqi power structures over the last 15 years. Weakening and possibly reducing this Iranian grip, through an appeal to Iraqi nationalism, will not solve Iraq’s profound problems. Among other challenges, the Islamic State still has influence in some Sunni areas. Nevertheless, countering Iran’s power is still an achievable goal, worth pursuing.

Introduction

Since October 2019, Iraq has been plunged into renewed political crisis. This crisis shows no signs of being close to resolution and may well intensify in the period ahead. The crisis has a number of elements, relating to a variety of issues affecting the country. This includes the acute problem of corruption; the failure to restructure the economy in line with an agreement with the IMF in 2015, a bloated public sector, the lack of faith of young Iraqis in the political class; unresolved sectarian and ethnic issues in the country; and significantly, resentment over the penetration of Iraqi politics by outside actors.

An overriding reality affecting all elements of this present malaise is the presence in Iraq of an Iran-linked power structure. The latter is based on a combination of political organization and paramilitary muscle, and today it is the key power in the country, controlling the core decision-making process. This structure is largely the product of the methods of the Islamic Revolutionary Guards and its Qods Force. The application of these methods to the specific Iraqi context in the years since the US invasion of 2003, which eventually created a power vacuum opened the door for the penetration of Iran into the Iraqi power structures.

Other external actors – both states and sub-state entities – are also present in Iraq and exert influence in a variety of ways. These include Turkey, the United States and its allies in the anti-IS coalition, the Islamic State organization (which itself originated in Iraq, as an offshoot of al-Qaeda), and the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK).

The various crises taking place in Iraq and listed below might appear to be separate and discrete. Yet, they are the ingredients for the larger political crisis in Iraq. The Tahrir Square protests involve largely Shia young people, and are focused on socio-economic issues, specifically access to housing and employment, as well as corruption in government. Kurdish grievances are focused on the prevention by force of secession in 2017, and on an ongoing dispute over the proportion of budget and the amount of oil to be exchanged between Erbil and Baghdad. Sunni Arab grievances center on harassment by the Shia militias and the heavy-handed practices of government security forces in Sunni central Iraq. However, all are ultimately related to the Iran-dominated central power structure.

The international element to the crisis derives centrally from the escalating tension between the Iranian interests – focused on the push to expel the remaining 5200 strong US presence in the country, and relatedly, to use Iraq as a way station, on the arch of control Tehran seeks to establish from the Iraq-Iran border to the Mediterranean Sea – and the real interest of Iraq, as such, to stay out of harm’s way. Israel is not the only regional and global player eager to foil Iran’s designs: but the salience of Israeli actions has been on the rise. Most urgently, Israel wants to prevent the transfer and/or deployment of ballistic missiles from Iran to western Iraq.

Thus, while all these ‘files’ appear distinctive – and they certainly include forces who share nothing in terms of outlook or preferred outcome: from the Israeli and US militaries, to Iraqi Shia youth of no political affiliation, to Sunni Islamists, to Kurdish nationalists – what they have in common is that all the aforementioned are arrayed against the ‘system’ put in place by Iran in Iraq over the last 15 years. The ‘system’ in question includes formal political, paramilitary, and religious elements. It reaches deep into the official bodies of the Iraqi state. The guiding hand behind it is Iranian. This system today controls the commanding heights of power in Iraq.

This is not to say that the removal or defeat of this system would solve all or even many of the major problems in the country. The factors preventing normal development in Iraq are structural, and historical. They include the problematic sectarian mix in the country, deep and pervasive corruption in public life, little tradition or experience in the practice of representative government (beyond the purely formal structures put in place by the Americans after 2003), and long traditions of militarized politics in the Shia and Sunni Arab communities and even more so among the Kurds, who will remain a state within a state. None of these elements would be likely to be eclipsed or removed by the containment, rollback or defeat of the Iranian system which currently is the dominant force in the country. Nevertheless, this latter task is the most urgent one from the point of view of the western and Israeli interest.

This paper will outline the key players and forces within the pro-Iran system and in the various elements opposed to it. It will then give a detailed background on the latest events in Iraq, using exclusive sources from the ground, and will conclude with a discussion of current US and Israeli policy vis a vis Iraq, and with some recommendations regarding how this policy could achieve greater clarity and effectiveness.

The Iraq Political System and its Key Players

Since the US invasion of 2003, a formal power sharing system between the three largest ethno-sectarian groups has existed in Iraqi politics, according to which the prime minister will be a member of the majority Shia Arab community; the speaker of the parliament will be a Sunni Arab; and the president will be a Kurd. This “Lebanese model” supposedly ensures that no community can be entirely marginalized. But given the role of the prime minister as a chief executive, in Iraq’s parliamentary mode of government, it also formalizes the dominance of the Shia majority, at least in the areas where the government’s writ runs (not including the KRG). This is an almost inevitable aspect of the attempt to introduce democratic norms in Iraq.

This Shia domination is also reflected in the results of parliamentary elections for the 329-seat unicameral legislature in May2018. The first three largest lists all represented Shia Iraqis. (Sairoon, Fatah and al-Nasr). These achieved 54, 48 and 42 seats respectively. (A 4th Shia list, State of Law, won 25 seats, and a 5th, Hikma, 19). Thus, overtly Shia voices, closely or loosely linked to Iran, constitute over half of the parliament.

The prime ministership of Adel Abd al-Mahdi following the elections of 2018 was a result of an agreement between the two largest Shia lists – Sairoon of Muqtada al-Sadr and the pro-Iran militias of the Fatah list. While Abd al-Mahdi resigned on November 29, he and his government currently continue in a caretaker role. Adnan Zurfi was named as the new prime minister designate on March 17, 2020. Nominated by President Barham Salih after the main coalitions (Sadrists and pro-Iran militias) failed to agree on a candidate, Zurfi is a former governor of Najaf who worked closely with the US during the period of Sadrist insurgency against the coalition in Najaf (2004). Zurfi is a strong supporter of the demonstrations that have been under way since October 2019. Both Iran supported factions and the protestors in Baghdad and Najaf have expressed opposition to his appointment. Zurfi is a veteran of the Dawa party, a supporter of Abadi’s Nasr listand former supporter of State of Law. Nasr and Hikma lists and the Sunni Iraqi Forces alliance supported the appointment.

There is thus today in Iraq a clear Shia ascendancy. This means that whoever controls or dominates the Shia power structure in Iraq will also dominate the country. Currently, the dominant element within the Shia power structure of Iraq are the pro-Iranian factions.

Of course, one should not take a simplistic view of this. Not everything boils down to raw, measurable military or administrative power. The Shia leaders of Iraq seek to rule in cooperation with full or partial co-optation of Kurdish and Sunni elements, and the composition of Iraqi governments reflect this.

Within the Shia community, the moral authority and popularity of 89-year old Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani should also be noted. Sistani does not have a formal political party, though a number of powerful militias are associated with his name. But his fatwas are widely influential. He holds the prestigious status of Ayatollah ‘Uzma (a rarely bestowed term meaning ‘sign of God’) From Najaf, where he is the leading Ayatollah, he also exercises temporal power over a large budget. He has been described as the ‘spiritual leader’ of Iraq’s Shia. His fatwa of June 2014 declaring jihad against ISIS began the Shia mobilization that led to the establishment of the PMU. But Sistani does not have an organized political party and prefers to avoid open and direct involvement in politics, reducing his direct political significance. He has never been associated with the Iranian doctrine of Velayet Faqih, which requires obedience to the authority of the Supreme leader of Iran, and indeed his very position is a challenge to that concept.

Below is a list of all the groups to have won 10 or more seats in the Iraqi national elections of May 2018, with brief introductions, to provide a clearer picture of the political context:

Shia Actors

The Sadrists:

The movement led by Muqtada al-Sadr stood at the head of the Sairoon Coalition which won the largest share of seats in the elections of 2018. The Sadrists are a Shia Islamist trend. Muqtada’s father, Ayatollah Mohammed Sadeq al-Sadr founded the movement, to represent the Shia in opposition to Iraq’s Ba’athist regimes. He was murdered with two of his sons by the Saddam Hussein regime in 1999. Muqtada organized his father’s followers into an insurgent movement which fought the US in the period 2004-8. The movement now maintains an attached militia, the Saraya al Salam Brigades. These took part in the war against IS.

The roots of the movement’s base of support are in the poor Shia neighborhoods of Baghdad. Sadr is an opportunist leader with no firm orientation. In recent years, some analysts sought to present him as representing an ‘Iraqi Shia nationalism’ in opposition to pro-Iranian trends and groups. There is evidence to suggest that Saudi Arabia shared this view and sought to cultivate Sadr. However, Muqtada al-Sadr is currently seeking to move once more toward the pro-Iran camp, evidently seeing this as the true power center in the country. He took part recently in a meeting of the militias following the January 3 assassinations of Qods Force commander Major-General Qassem Soleimani and Popular Mobilization Units official Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis by the US. The meeting was held in Qom, on January 29. Sadr is currently a resident of this Iranian city, and for now at least should be considered an element of the pro-Iranian camp.

The Fatah Alliance

It comprises of the Pro-Iran ‘Hizballah’ type political-military movements. Iraq, in contrast to Lebanon, does not have a single ‘Hizballah’ type movement (i.e. a political-military formation created by the IRGC and in direct service to Iran). Rather, a variety of movements of this type exist. All these movements are currently gathered, from a military point of view, under the umbrella of the Popular Mobilization Units (al-Hashd al-Sha’abi, PMU), a formation established to fight against ISIS after the fatwa of Ayatollah Sistani in June 2014. Politically, the main militias united to form the ‘Fatah’ Alliance in the 2018 elections, scoring the second largest number of seats. The dominant pro-Iran militias today in Iraq are the Badr Organization, Kata’ib Hizballah, ‘Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq, and Kata’ib Imam Ali. All are elements of the Fatah alliance. An additional influential militia, Hizballah Nujaba, shuns formal political activity. Otherwise, these organizations follow the IRGC’s methods of combining political and military activity, and activity within the state system with independent paramilitary actions. An example of this is Badr’s activity within the powerful Interior Ministry, where many senior and junior operatives of the paramilitary Federal Police double as operatives for Badr.

The Islamic Supreme Council of Iraq

Formerly known as the Supreme Council for the Islamic Revolution in Iraq (SCIRI), this is an Iraqi Shia Islamist Iraqi political party, established in Iran in 1982 by Mohammed Baqir al-Hakim. It is pro-Iranian in outlook and was active on behalf of pro-Iranian and pro-Shia interests during the Iran-Iraq war against the regime of Saddam Hussein. Badr was the militia of this party until it split from it after the civil strife of 2006-7. Its power base is in the Shia south of the country. In July 2017 the movement leader ‘Ammar al Hakim announced that he was leaving the party to set up a new ‘non-Islamic national movement,’ to be known as al-Hikma, which won 19 seats in the 2018 elections.

The Da’wa Party and its derivative lists

Dawa is a pro-Iranian Shia party in Iraq, of long standing. Former Prime Ministers Nouri al-Maliki and Haider al-Abadi were both members of this trend. Mohammed Baqir al-Sadr (not to be confused with Mohamed Sadeq al-Sadr, founder of the Sadrist trend, who was his cousin) was the most influential theorist and leader of the movement in its early days in the 1970s. The movement supported Iran during the Iran-Iraq War. Against the backdrop of the war, Da’wa (“the Call”, a standard Islamist term for religious mobilization and social organization) launched an insurgency against the Iraq regime in the late 1970s. Sadr was executed by Saddam Hussein’s regime in 1980. The regime banned the party in the same year. After 2003, the party at times cooperated closely with the US, though Da’wa remained committed to its Shia Islamist outlook. Enjoying a series of electoral successes from 2005, Da’wa in 2018 instructed its members to vote for either of two lists led by party members and former prime ministers – Maliki’s State of Law list or Abadi’s Victory of Iraq list. As a result of this division, as well as its lack of a paramilitary capacity, the influence of this party has declined.

The Sunni Camp

Sunni Arab political representation in Iraq is divided and disorganized, with many local power centers and fewer national players.

Mutahidun

Chief among those forces with a national profile, is the Mutahidun, or ‘United for Reform’ alliance of Osama al-Nujaifi. The latter established the coalition in 2012, bringing together a number of the largest and most significant local Sunni blocs. The party favors the establishment of a Sunni federal region in Iraq, to take in parts of Ninawa, Salah al-Din and Anbar Provinces. Osama Nujaifi and his brother Atheel are scions of a wealthy Mosul Sunni family with a tradition of political activity going back to the days of the monarchy in Iraq (though this tradition was interrupted by the period of Ba’ath rule). Osama Nujaifi heads the moderate Sunni Hadba party within the list. The Nujaifis have been criticized by Shia rivals for their supposedly Muslim Brotherhood orientation and have been accused of maintaining links with Turkey. Turkey maintains a limited military presence in Ninawah Province, the stronghold of the Nujaifis.

The Kurdish Political Actors

Kurdish Democratic Party (KDP)

Dating back to 1946, the KDP is one of the two dominant parties in the Iraqi Kurdish region. It is a conservative and tribal party, dominated by the Barzani tribe and its leaders. Its first leader, Mullah Mustafa Barzani, was the chieftain of this tribe, and he bequeathed the leadership to his son, Masoud, who led the party until 2018. It is currently led by Nechirvan Barzani, grand-son of Mulla Mustafa and nephew of Masoud. Nechirvan Barzani also serves as president of the Kurdish Regional Government, the semi-autonomous Kurdish ruling structure in northern Iraq. The Prime Ministership is held by Masrur Barzani, who is the son of former President Masoud Barzani. Masrur is the director of the KRG’s powerful Intelligence and Protection agency. The KDP suffered a severe setback with the failed independence referendum of September 2017 and the subsequent loss of Kirkuk and its environs, at the hands of the Iraqi army and its allied Shia militias. But the KDP recovered to perform well in elections for the Kurdish parliament in September 2018. It won 45 of 111 available seats and emerged as the largest single faction. The KDP also remains the largest Kurdish party in the Baghdad parliament after the 2018 elections. It is dominant in the Erbil and Dohuk areas. Like the rival Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK), the KDP maintains its own armed forces – the Peshmerga. Although the KRG’s armed forces are formally united under the Peshmerga Ministry, in practice the force remains divided into KDP and PUK associated units. A paramilitary gendarmerie force, the 30,000 strong Zerevani is also loyal to the KDP.

Patriotic Union of Kurdistan

Founded in 1975, the PUK’s has its heartland in the Suleimaniyah area in north-east Iraq, close to the border with Iran. Unlike the KDP, the PUK’s roots are in leftist political organizations, and it rejects the openly tribal, conservative and traditional-Islamic outlook of the KDP. The PUK emerged from a unification of a number of left and far left Kurdish political groupings. Its initial support was among educated city dwellers. Suleimaniyah city is more secular and less traditional in outlook than the KDP stronghold of Erbil. Despite its leftist orientation, however, the PUK came to be dominated by its leader and founder, Jalal Talabani, and by members of his family (though this feudal element was never as accepted and institutionalized as in the rival KDP, from which the PUK emerged). Since Jalal Talabani’s death in 2017, and the long illness that preceded it, the party has been riven with factionalism and rivalries. Perceptions of widespread corruption led to a split in 2009 and the foundation of a new party, Gorran – Change. But with 18 seats in the Iraqi parliament after the 2018 elections to the KDP’s 25, the PUK remains a powerful force. It is more closely linked to Iran, while the KDP seeks to maintain good relations with Turkey.

The Non-Sectarian Party

Theoretically, all parties under the Iraqi constitution are supposed to transcend sectarian or ethnic lines, but as the list above indicates, this is not sustained in practice. The only significant non-sectarian party is Wataniya. The list led by former Prime Minister Iyad Allawi, a secular Shi’i and former Ba’athist, seeks to bridge the sectarian divide, and brings together a number of secular Sunni and Shia groups. The Iraqi Communist Party was also aligned with this list, though in 2018 it split from it to run alongside the Sadrists.

State Institutions

The Army and Police

The Iraqi Army is a nominally non-sectarian and non-political institution. Corruption remains a major issue. When war with ISIS began in 2014, it became clear that many army units existed on paper only. This was because of the practice whereby commanders would claim salaries for non-existent soldiers (or for ‘soldiers’ who were in fact civilians who had agreed to have their identities used in this way) and would then pocket the funds. Command positions were also sometimes made available for purchase. Efforts have been made to address this issue since the war against ISIS, but it remains a source of concern. As the demonstrations protesting the sacking of General Abd al-Wahab al-Saadi indicated, Iraqis do still invest a degree of trust in their armed forces. But in practice, the armed forces have become in recent years increasingly dominated by Shia Iraqis, rather than representative of the population as a whole. A quota system exists in all parts of the army apart from the CTS – the Counter Terrorism Service, also known as the Golden Division. But in practice, Shia commanders increasingly occupy the most influential positions. As one Sunni soldier interviewed by Foreign Policy in a recent article described the issue: ‘Although we have around 30-40 percent Sunni in top military ranks, they do not have as much power as Shiite ones. We have Sunnis with the rank of general working office jobs or are on standby, men on salary waiting for appointments.”1

Thus, the national army today remains an organization both beset by structural problems, and increasingly resembling the system it represents in its de facto domination by Shia Iraqis.

This situation is yet more pronounced in the Iraqi police force, which unlike the army, is subject to the deep influence of Shia militia groups – specifically, the Badr Organization. This influence works both in a top down and bottom up way. The police force is subordinate to the interior ministry, and Badr in its political orientation has deep influence within this ministry. The current interior minister Yassin al Yasiri is a non-political professional, but his predecessors were Badr members and the movement retains senior positions within the ministry. Also, many police personnel, particularly in the Federal Police and its elite Emergency Response Divison are also Badr members.

Current Issues and Latest Developments in Iraq

As indicated above, the political crisis – or rather, crises -– in Iraq are a reflection of a multi-layered, yet interrelated, set of problems.

Shia Unrest, and Iranian/Militia Role in its Suppression

Around 600 protestors have been killed in Iraq since the outbreak of unrest in early October 2019, with over 20,000 injured. The immediate precipitating factor for the unrest was the firing by the Iraqi government of a popular general, Abd al-Wahab al-Saadi, from his position as commander of the Counter Terrorism Service (otherwise known as the ‘Golden Division’) and his transfer to a more junior post at the Defense Ministry. Saadi, who the author interviewed during the Mosul campaign in 2017, is himself a Shia from Baghdad, but was widely respected as a non-sectarian figure and a professional military man.

The protests quickly expanded from this issue to embrace a variety of broader grievances, however. Demonstrators protested high unemployment, lack of access to affordable housing, lack of basic services and the failure of successive governments to address the country’s crumbling infrastructure, not rebuilt since the US invasion of 2003.

From the outset, the demonstrations were limited to Shia Arab parts of the country, and the protestors were almost entirely very young men. This is of particular importance, given that the commanding heights of power in Iraq today are held by Iraqi Shia parties, and that Shia forces hold an overall majority in the parliament, reflecting the fact that they constitute around 65% of the population of Iraq. The unrest shows that many Shia are estranged from the Shia leadership of the country. The demonstrations were from the outset affiliated with no particular movement and have not yet produced a coherent leadership or program.

Regarding the issue of outside interference, Iran is of course the main outside actor wielding influence in Iraqi politics and within the Iraqi system of governance in manifold ways. his was reflected in the visit paid by then Qods Force leader Qassem Soleimani to Baghdad in the week that the protests in Baghdad erupted in early October 2019. Soleimani, an Iranian official, addressed an Iraqi cabinet meeting and set the course for the hardline policy adopted in the first weeks against the protestors, resulting in hundreds of deaths. Iran-supported Shia militias played a central role in the subsequent suppression of the protests.

As one demonstrator in Baghdad told Iraqi reporter Ayman Aziz Botane on October 6, just five days after the protests began, “the government has changed its tactics, withdrawing its forces and bringing in other forces that belong to certain militias of the PMU – Khorasani and al-Nujaba (pro-Iranian PMU-affiliated militias). According to information I got from emergency forces and police, they started with 300 people and these were deployed at the top of buildings – they were all snipers.”

The role of the movement of Muqtada Al-Sadr has been of particular note in the demonstrations. Sadr, leader of the Saraya al-Salam militia and the Sadrist political movement, initially supported the protests and sent activists of his movement to provide ‘protection’ to the protestors. In early February, following the announcement of Mohammed Tawfiq Allawi as prime minister, Sadr withdrew his support from the protests. Contrary to some predictions, the protests have not entirely dissipated. But government forces have regained a number of key bridges and areas in Baghdad. Sadr’s supporters have themselves assisted in containing the protestors’ encampments. Members of the Sadrist ‘blue hats’ have taken over a number of key sites adjoining the protestors’ main site of encampment in Baghdad’s Tahrir Square.

The protests reflect a key deficiency in the Iran-led system which today governs Iraq: namely, its inability to provide answers to the pressing social and economic needs of the youthful Shia populations who it seeks to recruit through appeals to Islamic and sectarian loyalties. As of now, the socio-economic concerns expressed by the young Shia demonstrators in Iraq have not produced a coherent political challenge to the Iranians and their allies, but the strength, size and longevity of the protests should be a matter for concern for Iran.

Kurdish and Sunni Discontent

In addition to the current instability resulting from the protests, which involve almost exclusively Shia Iraqis, Iraq also faces the ongoing issue of sectarian and ethnic divides. This manifests itself in acute form currently in two areas. The status of the Kurdish north remains unresolved. While a Kurdish bid for independence was suppressed by force in October 2017, pro-separation sentiment remains high among the Kurdish population. Negotiations between the central government and the KRG have failed to conclusively resolve the issue of the amount of oil the KRG is required to provide to the Iraqi State Oil Marketing Company, and the related matter of the share of the national budget to be received by the KRG. When it was announced that an oil for budget deal had been reached on November 27, 2019, this led to expectations that the issue might finally be resolved.

However, the resignation of Prime Minister Abd al-Mahdi meant that the acting government henceforth had only caretaker status and could not sign an agreement with the KRG. Hence the agreement remains at present unratified, and the broader issue of Kurdish separatist sentiment is likely to manifest itself again in the future.

The second unresolved and no less acute sectarian issue is that of the Sunni Arab population, in the wake of the destruction of the ISIS ‘Caliphate’ – the quasi-state established by Sunni jihadis in Sunni Arab majority western Iraq in 2014, and destroyed by Iraqi government forces, allied Shia militias and a US-led Coalition in 2018. ISIS has ceased to exist as a quasi-sovereign force but remains very much in existence as an insurgent network.

The organization is currently reconstituting itself and possesses an extensive infrastructure of support particularly in rural areas of central Iraq. In areas contested between the Iraqi central government and the KRG, such as Makhmur, ISIS has flourished, taking advantage of the poor to non-existent communication between the Iraqi security forces and the Peshmerga to insert itself into these areas.

According to recent studies by the Pentagon, the Institute for the Study of War, and the UN, ISIS still has around 30,000 fighters available to it across Iraq and Syria. 2 It also does not lack for funds. ISIS has access to hundreds of millions of dollars deriving from its four-year taxation of the caliphate’s inhabitants, its looting of the banking system when it entered Mosul in June 2014, and its trade with both the Assad regime and rebels during the course of the war.

It also has existing networks of support on the ground. In Iraq in early 2019, for example, this author witnessed the lines of support and communication that Islamic State is building in the area south of Mosul city: from the town of Hamam Alil, across the Tigris River, through remote villages and hamlets, to the caves of Qara Chouk; in the Hamrin Mountains in Diyala province, Hawija, eastern Salah al-Din province, and Daquq.

ISIS fighters are able to travel across this area because of the support of local villagers, who leave food and water supplies for the movement’s fighters. In the Makhmur area, evidence has emerged that ISIS fighters have imposed taxes on local farmers, whose fields are burned if they refuse to pay. Contrary to some reports, ISIS does not appear close to an attempt at retaking territory. But as an insurgent network it is very much alive.

The Islamic State, however, is only one manifestation of a larger issue, namely the very great alienation of large parts of the Sunni Arab population of Iraq from the ruling order in Baghdad, which is Shia in nature and in large part loyal to or supportive of Iran. This is a structural issue not dependent on the fortunes of this or that Salafi jihadi organization.

It is exacerbated, however, by the growing strength of the pro-Iran element in Iraqi politics and consequently of the Shia militias in policing and security. The Sunni protests of 2012-13 were to a considerable extent triggered by the increasingly sectarian policies of then Prime Minister Nuri al-Maliki. Maliki’s sectarian policies included the detention of thousands of Sunnis by the selective use of anti-terror laws, the widespread torture of detainees, and the failure to stick to a power sharing agreement with the non-sectarian Iraqiyya list, instead concentrating power in the prime minister’s own hands, and a few exclusively Shia allies. Following the defeat of ISIS, the politics then represented by Maliki seemed to be victorious – but may yet exacerbate tensions. This is being manifested in Sunni areas in the presence of Shia militias, and in ongoing efforts on their part to acquire land areas on the strategic corridor to the border with Syria. Efforts at land grabs and other high-handed tactics used by the Shia militias ensure the continued alienation of Arab Sunnis.

The International Dimension: The Iranian System in Iraq vs. the US, Israel and Regional Players

The killing of Iranian Qods Force commander General Qassem Soleimani by the US close to the Baghdad International Airport on January 3 focused media attention on the issue of the Iranian political-military infrastructure in Iraq, and the possibility that this structure might be mobilized against the 5200 strong US presence in the country. In fact, however, such an effort on the part of the militias had already been under way since the beginning of 2019. Indeed, the killing of Soleimani was a US response to this ongoing militia campaign.

As far back as February 2, 2019, Iraqi security forces found and defused three missiles that had been set on a timer to be launched at the US-controlled al-Asad base. The missiles were defused fifteen minutes before they were set to launch.

On February 4, 2019, Ja’afar Husseini, spokesman of Ktaeb Hizballah, one of the most powerful of the Shia militias, warned that clashes between the militias and the US “may start at any moment.” This was the second such warning issued by the movement. “There is no stable Iraq with the presence of the Americans,” Husseini declared. His words were echoed by Qais al-Khazali, leader of the Asaib Ahl al-Haq militia, who similarly declared that Iraq’s security forces and “strong society” could easily expel the US service members currently deployed in Iraq. The tempo of attacks increased toward the end of 2019, while still failing to garner much major media attention. According to a report in Bloomberg on December 7 no less than eight separate attacks took place on Iraqi facilities hosting US troops in November and early December.3

Thus, the events that led to the killing of Qods Force commander Qassem Soleimani, and key PMU official Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis on January 3 were preceded by a long period of gradually increasing tensions between the Shia militias and the American presence in Iraq. The January 3 assassinations were a US response to an emergent Shia militia insurgency to expel US forces from Iraq.

After the Assassinations

Following the killings, the militias unsurprisingly appeared to be in disarray. In this regard, the absence of al-Muhandis was no less important than that of Soleimani. Muhandis’ Kata’ib Hizballah has been described as the ‘central nervous system’ of the IRGC’s Qods Force in Iraq. Precisely because the structures built by the Qods Force under Soleimani were only semi-formal, they depended to a great extent on personal relationships and the personal authority possessed by particular individuals. Unlike in a formal bureaucratic hierarchy, where an individual who dies is simply replaced by another invested with similar authority, in the case of Soleimani and al-Muhandis, their authority rested on a web of personal relationships and the perception of them as non-corrupt, authentic representatives both of Iranian power and of the Islamic revolutionary idea as formulated by Iran.

This type of authority cannot simply be bequeathed. Reports suggest that no replacement for Muhandis has yet been found. Badr Organization leader Hadi al-‘Ameri was initially reported as likely to assume the position of de facto leader of the Shia militias. But al-‘Ameri is widely regarded as corrupt and lacks the authority that Muhandis possessed. Later reporting suggested that Mohammed Kawrathani, the Najaf-born representative of Lebanese Hizballah in Iraq, was acting as the de facto coordinator of the militias in Iraq, with the authority of Lebanese Hizballah leader Hassan Nasrallah behind him. Some reports also suggested that Muqtada al-Sadr was making a bid for this position, proposing his movement with its wide and deep networks of support as the most appropriate candidate to form the parallel to Lebanese Hizballah in the Iraqi context.

An additional emergent player worth noting is Akram al-Ka’abi, of the Hizballah Nujaba organization. Nujaba emerged from Asaib Ahl al Haq (AAH) in 2013 (AAH was itself a split from the Sadrists). Nujaba took an active role in the Syrian civil war. Al-Kaabi has clearly had major ambitions for his movement from the outset. A picture circulated of the Nujaba leader with new Qods Force Commander Esmail Ghaani shortly after the assassinations of Soleimani and al-Muhandis. The picture was taken at the meeting in Qom following the killings, at which a number of other senior representatives of Iraqi pro-Iran Shia militias were present (including Sadr).

Ka’abi’s potential role appears to be that of a mediator, rather than a leader, of the militias. The relatively junior position of Nujaba enables him to play this role. Also, important, Ka’abi is a former Sadrist, who was a commander in Sadr’s Mahdi Army during the Shia insurgency against the Americans in Iraq. As such, he is well-placed to play a mediating role in the crucial relationship currently developing between Sadr on the one hand and the pro-Iran militias on the other.

But whether Kawrathani or some other figure eventually manages to reassert centralized authority over the militias, it is clear that the disappearance of Soleimani and Muhandis has dealt a severe blow to the coherence and unity of the PMU. In this regard, it should be remembered that the militias are not simply units of a single army. Rather, they are separate organizations with their own sources of funding, patronage hierarchies and powerful leaders, who do not necessarily feel obligated to obey the instructions of an individual simply because of his claim of authority. It is thus likely to take some time before the militias achieve a similar level of cohesion to that which they possessed under the de facto leadership of al-Muhandis.

The militias appear to be currently seeking to respond to the killing of their leaders with an increase in the quantity and intensity of their attacks on US facilities and personnel in Iraq. Iran of course responded directly in its ballistic missile attacks on the Asad air base and a facility near Erbil where US and coalition troops were based. Subsequent to this attack, the militias on February 13 carried out a rocket attack on the K1 base near Kirkuk. This was the location where the US contractor was killed on December 27, in the attack which triggered the US strike on Soleimani and Muhandis. The attack took place immediately following the marking of 40 days since the death of Soleimani et al. A rocket attack on the Union III base which houses US and Coalition troops in Baghdad’s Green Zone took place on February 16.

On March 7, 30 Katyusha missiles were launched at Camp Taji. Three Coalition personnel were killed. The US responded in force against 5 targets of Ktaeb Hizballah south of Baghdad. This in turn was followed by another launching of at least 25 107 mm rockets on Taji on March 14. Three additional US troops were wounded.

Ktaeb on March 5 issued a statement demanding that all Iraqi parties, companies and forces cease cooperation with the Americans by March 15 or face the consequences. It looks likely that for now, the militias will continue the pattern of loud rhetoric and ongoing harassment of US facilities. Their intention will be to combine this with political action in order to precipitate a US withdrawal from Iraq. They are likely strengthened in their optimism regarding the feasibility of this objective because of the relative incoherence of the reasons for the current US mission.

The Israeli Angle

The dominant role of Iran in Iraq, and the activities of the IRGC controlled Shia militias unimpeded by and often in cooperation with the official state security forces are a matter of concern to Israel. Iran seeks to dominate the land area between the Iraq-Iran border and the Mediterranean Sea and all the way to the Israeli border. Recent events suggest that the militias work in tandem with the security forces of Iraq, following Iranian directives. This is problematic for Israel, primarily because of the use made by Iran of areas under its direct control in Iraq for the storage, transport and/or deployment of missiles aimed at Israel.

A recent article authored by IDF Brigadier General (res.) Assaf Orion and veteran Iraq analyst Michael Knights focused on indications that Iran is making use of its Iraqi militia clients to deploy short range ballistic missiles (SRBMs) in the deserts of western Iraq – with the intention that these could be launched against Israel at a time of Iran’s choosing.4 This is not the first public airing of Iranian activity in this regard. A Reuters report on August 31, 2018 was the first to note the concerns of US and Israeli intelligence agencies.5 The article detailed the transfer by the IRGC’s Qods Force of Zelzal, Fateh-110 and Zolfaqar missiles and launchers to western Iraq. The Zolfaqar has a claimed range of 750 km – putting Tel Aviv within its range if it was deployed in this area. The distance from al-Qaim on the Iraqi Syrian border to Tel Aviv is 632 km.

Teheran has also established facilities for missile production in western Iraq and is employing Iraqi citizens to carry out this work. The Reuters article named the areas where production is taking place as ‘al-Zafaraniya, east of Baghdad, and Jurf al-Sakhar, north of Kerbala. It is noted that “These Shia proxies have reportedly developed exclusive use of secure bases in the provinces of Diyala (e.g., Camp Ashraf), Salah al-Din (Camp Speicher), Baghdad (Jurf al-Sakhar), Karbala (Razzaza), and Wasit (Suwayrah).”

In Iraqi, US and Israeli intelligence circles it is widely accepted that the “militias have developed a line of communication and control to Iran through Diyala, allowing them to import missiles and equipment without government approval or knowledge.”6

The ability of Iran to operate a de facto contiguous line of control across Iraq, and thence to Syria, Lebanon and the borders with the Golan Heights is thus not under serious doubt. It appears that Teheran has begun to station SRBMs along this route, directed at Israel, and crewed by the Qods force-directed militia franchises – an arrangement intended to provide Iran with deniability in the event of their being used.

Media reports suggest that Israel has already on at least four occasions acted against this Iranian infrastructure on Iraqi soil. Israel will need to factor in the need for continued self-reliance in defending its security in the widening sphere of de facto Iranian control, which now takes in large parts of Iraq and appears set to continue to do so. This may lead to complications with the US, since there were indications in 2019 that the US found Israeli air action in Iraq to be contrary to its efforts to avoid escalation in Iraq with pro-Iranian forces.

Regarding areas of critical importance along the border, in addition to the sites listed above, it is important to remember that the al-Qaim/Albukamal border crossing is currently under control of the IRGC and allied Shia militias, on both sides of the border. The crossing constitutes a vital transport node under exclusive Iranian control, which is used for transporting weaponry and fighters. As of now, the Shia militias have freedom of movement on both sides of the border (though the US presence at al-Tanf in Syria requires the IRGC and its allies to take a bypass route via Mayadeen when heading westwards.) Iran needs to maintain the current balance of forces in Iraq (or improve it in its favor) in order to preserve this de facto contiguous area of control which stretches from Iran to the Mediterranean sea and the Quneitra crossing into Israel.

The militias’ strength is also a matter of concern for Jordan, which fears that the American presence on its soil could make it a target for an attempted Iranian revenge for the killing of Qods Force commander Qassem Soleimani on January 3, 2020. US embassy staff in Baghdad were evacuated to Jordan after the January 3 events. Jordan is worried that its neighbor Iraq will become a base for undermining the Hashemite regime. They may face a pincer movement from Iraq and Syria

Conclusion

At the present time, several problems of long standing in Iraq appear to be reaching a point of crisis simultaneously. These crisis systems do not necessarily combine to push Iraq in a particular political direction. Rather, they may be in tension with one another.

Many observers of Iraqi politics, for example, considered that the killing of Soleimani would have the effect of dampening enthusiasm for the protests taking place in Tahrir Square in Baghdad. This was because it was assumed that the Soleimani killing would revive the dynamic of Shia sectarianism and anti-US anger among the Iraqi Shia majority, youthful members of which also formed the great majority of the demonstrators. Yet this expectation has only partly been fulfilled. Attendance at the demonstrations did decline in the period immediately following the killing. Both the Iran-linked political/military groups, and the Sadrists attempted to use the killing for the purposes of sectarian mobilization precisely to deflate the protests. Sadr’s party organized a ‘million man’ march in Baghdad intended to commence a rival street level movement committed to the expulsion of the US from Iraq. However, the protests in Tahrir Square have not been entirely dissipated by these attempts and are continuing.

Continued attacks on a limited scale by the Iran-backed militias against the US presence are likely. The Iranians appear to be playing a long game in Iraq which is intended to result in their domination of the commanding heights of policymaking in the country. Triggering a reaction from the current US Administration would be counterproductive in achieving this goal – particularly since the general trend in the US, now stretching over both the Trump and Obama Administrations, is toward reducing commitments in the Middle East. The model for Iranian domination of Iraq is Lebanon, where the process of turning the Iranian proxy Hizballah organization into the dominant force, and inserting its influence into the key power nodes, political, military, intelligence and economic in the country is already far advanced.

In Iraq, today, with the turn of Sadr towards Teheran and the growing power of the openly IRGC-supported Fatah list, Iran is already the key element behind the power structure in Iraq. Still, the west has significant and powerful allies on the scene, including the Kurdish Regional Government, and forces which might work with the west, in order to limit and reduce Iranian power, including the Mutahidun alliance, local Sunni groups, and the largely Shia demonstrators who take a firm position against Iranian and Hizbullah meddling. Thus, the US should seek to engage in the proxy political struggle inside Iraq, while accepting that this may constitute a blocking action, rather than an effort likely to result in the wholesale expulsion of Iranian influence in Iraq.

No illusions, however, should be invested in the main current Shia political movements. They are unlikely to be diverted from the current trend toward consolidation around the pro-Iranian center. The US should consider concentrating the presence of its personnel in Iraq in greater numbers in the secure Kurdish north. The Kurdish area remains a safe and supportive environment for US personnel, in contrast with both Sunni and Shia Arab areas where anti-US sentiment is strong, and stringent security measures are a necessity. The US should declare its support in principle for Kurdish independence. The present levels of US troops in the country should be maintained, but defenses at al-Taji and Balad bases should be increased, in expectation of stepped up Shia militia activity against them in the period ahead.

Israel, for its part, will in the period ahead need to keep a close eye on security developments related to the consolidation of Iranian power in Iraq. The deserts of western Iraq are likely to continue to form a site for Iranian missiles. The southern border crossing at al-Qaim/Albukamal is controlled by the Shia militias and the IRGC, and forms part of a contiguous area of control continuing to the border with Lebanon and to the Quneitra Crossing.

But while Iranian primacy in Iraq is not at all desirable from an Israeli point of view, it also does not constitute a catastrophe. Lebanon dominated by Hizballah has proven not immune to the logic of deterrence, given the strength and reach of Israel’s armed capabilities. It is likely that Iran-dominated Iraq might prove similarly amenable, over time. Iraq looks set to continue to be a strife-torn, dysfunctional space in which the state exercises only partial sovereignty, while the territory it nominally rules over forms a site for a variety of contests fought out between sub-state actors, foreign powers and sub state actors assisted or controlled by foreign powers. This will continue to provide scope for actions by Israel’ the US, and regional players aimed at weakening Iran’s grip, even if the full overthrow of Iran’s influence may not yet be within reach.

[1] Vera Mironova, Daha Tahseen Assi, “The Iraqi Military wont Survive a Tug of War between the United States and Iran,” Foreign Policy, January 15, 2020. https://foreignpolicy.com

[2] Jennifer Cafarella, with Brandon Wallace and Jason Zhou, “ISiS’s Second Comeback: Assessing the Next ISIS Insurgency,” Institute for the Study of War, July 23, 2019. http://www.understandingwar.org

[3] Anthony Capaccio, “Rockets hit 2 Iraqi air bases where US Forces Stationed,” Bloomberg, December 7, 2019. https://www.bloomberg.com

[4] Michael Knights and Assaf Orion, “If Iran Deploys Missiles in Iraq: US-Israeli Response Options,” Washington Institute for Near East Policy, Policywatch 3119, May 3, 2019. https://www.washingtoninstitute.org

[5] John Irish, Ahmed Rasheed, “Exclusive: Iran moves missiles to Iraq in warning to enemies,” Reuters, August 31, 2018. https://www.reuters.com

[6] Ibid.

photo: Izzedine / CC BY-SA 3.0

- בניית אתרים

- בניית אתרים