תורכיה מוצאת את עצמה היום בצומת דרכים היסטורי שבו עליה להחליט האם להמשיך לבדה מול ישראל, מצרים, יוון וקפריסין – או לאמץ שיתוף פעולה אזורי

מבוא

מזרח הים התיכון שב והופך כיום זירה למאבקי כוח משמעותיים. האזור עבר שינויים דרמטיים בעשור האחרון. “האביב הערבי”, התערבות הצבא לשינוי המשטר במצרים, מלחמת האזרחים בסוריה, גלי הפליטים והידרדרות היחסים בין תורכיה למדינות המערב ולישראל – כל אלה ממלאים תפקיד חשוב בדרמה זו.

רשימה זו של התפתחויות מרחיקות לכת עדיין איננה ממצה את התמונה המלאה של הכוחות המשנים את האזור. רוסיה מבססת כאן שוב נוכחות קבועה, בעוד שסין מבקשת עוגנים לתוכנית “חגורה אחת, דרך אחת”. לא זאת בלבד, אלא שמשאבי הגז הטבעי שהתגלו לאחרונה הפכו את מזרח הים התיכון לאחד האזורים הימיים הגאו-אסטרטגיים המשמעותיים ביותר, התפתחות שעשויה לעצב מחדש את מאזן הכוחות האזורי ואת הדינמיקה של מדיניות האנרגיה האירופית.

העתודות העשירות של גז טבעי וההזדמנויות למיזמים משותפים הופכות את מזרח הים התיכון לאזור בעל חשיבות בעיצוב מאזן הכוחות, וסוללת את הדרך לבריתות חדשות. כשחקנית מפתח באזור, תורכיה מוצאת את עצמה בצומת דרכים היסטורי שבו עליה להחליט האם להמשיך לבדה מול ישראל, מצרים, יוון וקפריסין, או לאמץ שיתוף פעולה אזורי.

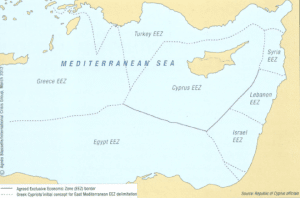

אין ספק שגילוי שדות הגז הגדולים במצרים, בישראל ובקפריסין פתח אפשרויות חדשות למיזמי צינור משותפים שיובילו את השפע לאיטליה ולמערב אירופה דרך יוון, או לאספקת גז למתקני ניזול LNG)) במצרים.1 תוכניות אלה סללו את הדרך לבריתות חדשות בין אתונה, ניקוסיה, ירושלים וקהיר, בריתות שהעיתון הממשלתי התורכי הפרו-ממשלתי, יני שפאק (Yeni Şafak), תיאר כ”ציר הרשע”.2

בהתחשב בשלום הקר השורר בין ישראל ומצרים, מנהיגי מצרים נמנעים מלהתייצב מול המצלמות לצד עמיתיהם הישראלים, אולם הודות לאירוח של יוון וקפריסין הצליחו ארבע המדינות ליצור רביעייה בשתי פלטפורמות תלת-צדדיות נפרדות. האחת כוללת את ישראל, יוון וקפריסין, ובמקביל לה מצרים, יוון וקפריסין (שהפסגה המשולשת האחרונה שלהן, השישית עד כה, התקיימה בכרתים ב-10 באוקטובר 2018).

מלבד הפקת רווחים מתגליות הגז, יש לארבע הבירות הללו סיבה משותפת נוספת לכרות ביניהן ברית: תורכיה. ואכן, לאור מדיניות החוץ הנאו-עות’מאנית שלה, המתנערת לעיתים קרובות מאילוצים פוליטיים ומשיקולי ריאל-פוליטיק, נראה כי תורכיה היא הקטליזטור להתקרבות זו. המחלוקות הכרוניות המתמשכות בין אנקרה לאתונה בכל הנוגע למדף היבשתי, ואף לגבול ההיסטורי בים האגאי כפי שהותווה בהסכמי לוזאן, והמחלוקת עם ניקוסיה בשאלת קפריסין הכאובה, משקפות עוינות בת מאות שנים. עוינות היסטורית זו חברה כעת לתמיכתו של הנשיא רג’פ טאיפ ארדואן באסלאמיסטים, לעמדתו הפרו-פלסטינית, להתערבותו הפרובלמטית בענייני ירושלים, לניסיונותיו לחולל דה-לגיטימציה בשלטונו של נשיא מצרים, עבד אל-פתאח אל-סיסי (בעקבות הפלת משטר מורסי במצרים ב-2013) וליחסיו עם טראמפ. כל אלה דחקו את שאר הכוחות האזוריים לגיבוש ברית-למחצה נגד אנקרה. גם העוינות הגלויה והמעורבות הצבאית של אנקרה בצפון סוריה השפיעו לרעה על מעמדה של תורכיה במזרח הים התיכון.

לאור זאת, אנקרה מצאה את עצמה מבודדת באזור. לאחר שסולקה מכל המיזמים האזוריים הפוטנציאליים, אנקרה נראית כמי שלוהקה לתפקיד משביתת השמחות האזורית. במסגרת תפקידה זה אנקרה מפעילה לחצים כבדים בשאלת קפריסין, תוך שהיא מערערת על גבולות המים הכלכליים של קפריסין בניסיון לסכל את פרויקט הגז הטבעי האמור, אף כי אין הוא עובר בשטח תורכיה. בפסגה שנערכה בנובמבר 2018 בכרתים גררה עמדתה של תורכיה ביקורת חריפה מצד מצרים, יוון וקפריסין.

על מנת לנתח את יסודותיו של משחק השחמט האזורי, מאמר זה מציג את השחקנים המרכזיים, את האינטרסים שלהם, את הדינמיקה העיקרית המניעה את מדיניות החוץ שלהם ואת המחלוקות הקיימות ביניהם, תוך התמקדות בתורכיה. תחילה תוצג חשיבותן של תגליות האנרגיה במזרח הים התיכון, וייסקר המצב המשפטי הנוגע אליהן. לאחר מכן יונח בסיס גאוגרפי להבנת הדינמיקה במזרח הים התיכון והאנטגוניזם הנוכחי של מדיניות החוץ התורכית.

חשיבותן של תגליות הגז במזרח הים התיכון, וההקשר המשפטי

בעולם שבו התפתחות כלכלית תלויה במקורות אנרגיה ולנתיבים של קווי האנרגיה יש חשיבות אסטרטגית, ושבו אנרגיה משמשת להטלת סנקציות כלכליות, שיקולי אנרגיה הופכים למרכיבים חשובים במדיניות ארוכת הטווח. כך קרה שמדינות מזרח הים התיכון שאין ברשותן שדות נפט ביקשו לנסות את מזלן והחלו לערוך מחקרים סייסמיים בים התיכון.

בשנת 2003 גילתה חברת האנרגיה Shell שדה גז טבעי שהוערך ב-42 מיליארד מטר מעוקב (קמ”ק) בבלוק NEMED (צפון-מזרח הים התיכון), באזור דלתת הנילוס3 בדצמבר 2017 נכנס לייצור שדה זוהר, מאגר הגז המצרי שהתגלה ב-2015 בשולי קו התחום שבין המים הכלכליים של קפריסין ומצרים, עם עתודה משוערת של 849.50 קמ”ק.4 ב-2009 גילתה ישראל את שדה הגז תמר 1 (255 מיליארד מ”ק) וב-2010 את לווייתן (491 מיליארד מ”ק). הקרבה הגאוגרפית של לווייתן דרבנה גם את הקפריסאים לחפש גז, וב-2011 הודיעה חברת נובל אנרג’י האמריקנית על גילוי גז טבעי בבלוק 12 מול חופי קפריסין – מאגר אפרודיטה (129 מיליארד מ”ק). תגליות אלה שינו מן היסוד את התמונה האסטרטגית במזרח הים התיכון,5 כשהגז משמש בסיס לשיתוף פעולה כלכלי ואסטרטגי בין המדינות. עתודות הגז המשולבות באזור מתקרבות ל-707 מיליארד מ”ק, נפח הממקם אותן בין 30 שדות הגז הגדולים בעולם, גדול ממרבית שדות הגז בים הצפוני.6

בשנת 2013 אימצה ישראל מדיניות ייצוא המאפשרת לה למכור 50% מיתרות הגז שלה לשוקי חוץ.7 קפריסין, שהשוק המקומי שלה קטן והיא אינה שותפה לאוריינטציית הייצוא הישראלית, לא נקטה מדיניות ייצוא ברורה וגם לא שחררה נתונים רשמיים ברורים בעניין זה.8 אי-ודאות דומה אופף גם את מצרים: שדה זוהר יספק גז בעיקר לשוק המקומי, ויעשה שימוש בשני מתקנים לא מנוצלים להפקת גט”ן לייצוא. לפיכך, בשלב זה עדיין לא ברור האם הגז המזרח ים-תיכוני יפחית את תלותו של האיחוד האירופי ברוסיה.9

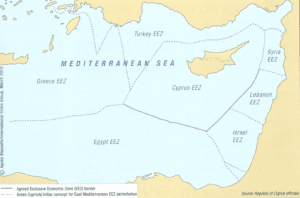

אמנת האומות המאוחדות לחוק הים (UNCLOS), שנכנסה לתוקפה בנובמבר 94, ביקשה לכונן פתרונות מקובלים למחלוקות הנוגעות להפקה פוטנציאלית של משאבים טבעיים מקרקעית הים. בשל אימוצה הנרחב הוחל להתייחס בהדרגה להוראות האמנה כחלק מהמשפט הבינלאומי המנהגי. אמנה זו קובעת כי לכל מדינת חוף יוגדרו 12 מייל ימי (כ-22 ק”מ) של מים טריטוריאליים ו-200 מייל (כ-370 ק”מ) של אזור כלכלי בלעדי (EEZ), וכן מדף יבשתי שישתרע על 250-300 מייל. עקרונות היסוד של אמנת הים התקבלו באופן נרחב כאמות מידה משפטיות.

ישראל, תורכיה, ארה”ב וונצואלה לא מיהרו להצטרף לאמנת הים של האו”ם, וחוסר העניין של ישראל ותורכיה באמנה זו אכן מקשה על פתרון מחלוקות בין מדינות החוף באזור לשכנותיהן. באופן בלתי נמנע התפשטו יחסי העוינות המסורתיים מהיבשה גם לשטחים הימיים. בעיות הליבה בהקשר זה כוללות את העוינות התורכית-יוונית בכל הנוגע לזכויות ריבוניות על המדף היבשתי בים האגאי, שאלת קפריסין והשלכותיה על המים הטריטוריאליים, המתיחות בנושא זכויות המים הכלכליים בין קפריסין היוונית לקפריסין התורכית ומחלוקת הגבול הימי בין ישראל ללבנון. הממד המשפטי במקרים אלה רק מחריף את המתחים הפוליטיים, האידאולוגיים והאסטרטגיים הקיימים.

יחסה של תורכיה למדינות מזרח הים התיכון

יחסה של תורכיה למדינות מזרח הים התיכון נובע מדוקטרינת חוץ עדכנית המכונה “בדידות מזהרת” (דיארלי ילנזליק), כפי שהוצגה על ידי דוברו של הנשיא ארדואן, איברהים קאלין, במקום היומרה, שהתנפצה זה מכבר, של “אפס בעיות עם השכנים”. אף כי דוקטרינה חדשה זו ננטשה לכאורה ב-2016, עם הפיוס בין תורכיה לישראל, מצבם הנוכחי של היחסים הבילטרליים בין המדינות וגישתה של תורכיה למשטרים במצרים ובסוריה מעידים על ההפך המוחלט. ברוח השקפת עולמו של קאלין, תורכיה בחרה לעצב את מדיניות החוץ שלה על פי פרשנותה לערכי המוסר האסלאמיים, עיקרון שפירושו בהכרח צמצום קשריה עם “מדינות לא מוסריות”. על פי היגיון זה, תורכיה אינה יכולה לנרמל באופן מלא את יחסיה עם ישראל משום שזו האחרונה ערכה שלושה מבצעים צבאיים ברצועת עזה (אם כי האינטרסים של מפלגת השלטון חייבו את ההנהגה התורכית להימנע מכל פגיעה של ממש בקשרי הסחר והכלכלה, שדווקא התרחבו בשנים האחרונות). היא גם אינה יכולה להדק את היחסים עם מצרים תחת משטרו של הנשיא א-סיסי, משום שבעיני התורכים הוא הדיח בהפיכה בלתי לגיטימית את האחים המוסלמים, וודאי שאינה יכולה לשקם את היחסים עם בשאר אל-אסד לאור מלחמת האזרחים העקובה מדם שניהל בסוריה.10 יחסיה הפורמליים עם ירדן טובים יותר, אם כי מתחת לפני השטח שוררת בעמאן דאגה עמוקה נוכח החתרנות התורכית בירושלים.

בה בעת, עם קו חוף שאורכו 1,577 ק”מ בצפון מזרח הים התיכון ונוכחות צבאית בקפריסין, אנקרה עדיין רוצה שארבעת יריביה יכירו במעמדה, וודאי שלא יתעלמו מיכולותיה ומהשפעתה במשוואה המזרח ים-תיכונית. למרבה האירוניה, אנקרה מבקשת להיכלל בכל פרויקט אנרגיה פוטנציאלי במזרח הים התיכון תוך חיזוק מעמדה כגשר אנרגיה לאירופה, למרות מדיניות החוץ האנטגוניסטית שלה. מנקודת מבט תורכית, שילובה של תורכיה בשיתוף פעולה אנרגטי אזורי יגדיל את התלות ההדדית בין המדינות ויחליש את התנגדותן ללחצים התורכיים בשאלת קפריסין (או עזה).11 תלות הדדית זו תחזק באופן בלתי נמנע את ידיה של תורכיה מול ארבע השותפות האחרות, משום שהיא תעמיד אותה בצד המקבל של הצינור. במילים אחרות, שילובה של תורכיה בפרויקט אזורי זה יאפשר לאנקרה לנטרל את העליונות הכלכלית והפוליטית של קפריסין היוונית על פני קפריסין התורכית (אחת ההשלכות הנובעות מחברותה של קפריסין, כמדינה, באיחוד האירופי). היא עלולה אף להשתמש במיקומה הגאוגרפי כדי להפעיל לחצים על מדינות מזרח הים התיכון באמצעות סגירת ברז האנרגיה לאירופה כל אימת שהדבר ישרת את האינטרסים והמטרות האידאולוגיות שלה.

מדיניות החוץ התורכית – בצל השקפת העולם האסלאמיסטית של ארדואן, שלא תמיד נענית לשיקולים של ריאליזם פוליטי – עלולה להיות בלתי ניתנת לחיזוי. למרות זאת ערך שר האנרגיה, יובל שטייניץ, שני ביקורים בתורכיה, באוקטובר 2016 וביולי 2017, כדי לבחון את ההצעה להקמת צינור ישראלי-תורכי, שאורכו המשוער כ-482 ק”מ בעלות מוערכת של כ-7 מיליארד דולר. הואיל ותורכיה מייבאת יותר ממחצית מהגז הטבעי שלה מרוסיה, וכמעט חמישית ממנו מאיראן, ייבוא גז טבעי מישראל עשוי לסייע לה בהקטנת התלות האנרגטית שלה ברוסיה ובאיראן,12 אולם בשל הידרדרות היחסים בין שתי המדינות וההתערבות המתמשכת של ארדואן בסכסוך הישראלי-פלסטיני, במיוחד בכל הנוגע לעזה ולירושלים, לא נראתה עד כה כל התקדמות ממשית בעניין זה, וסיכויי הפרויקט כיום אינם גבוהים.

אם צינור הגז של מזרח הים התיכון אכן יחצה את תורכיה, הוא יחזק את מעמדה בעולם כ”רכזת” טבעית לשינוע אנרגיה. תורכיה כבר מארחת בשטחה צינורות גז טבעי, ביניהם קו הזרם הכחול (Blue Stream) והצינור הדרום קווקזי (באקו-טביליסי-ארזורום, BTE), וסביר להניח שתארח גם את צינור “הזרם התורכי” (Turkish Stream) וצינור הגז הטרנס-אנטולי (TANAP). כדי לממש יעדים אלה תורכיה עלולה להתפתות ולהשתמש גם בחיל הים החזק שלה, נוסף למאמצים דיפלומטיים, על מנת להרתיע ולהניא את ארבע המדינות,כמו גם חברות גז בינלאומיות פוטנציאליות אחרות, מהשקת פרויקטים אזוריים שאינם כוללים את אנקרה.13

מאמציה של תורכיה לחזק את השפעתה במזרח הים התיכון אינם מוגבלים רק לממד הימי. בשנים האחרונות נקטה אנקרה מדיניות פעילה שמהותה תמיכה באחד הצדדים היריבים במדינות המתמודדות עם חוסר יציבות פנימי, בעיקר בלבנט ובצפון אפריקה, ובכלל זה סוריה, עזה מול הרשות הפלסטינית, והממשלות היריבות בלוב. במקרה של סוריה החליטה אנקרה לעלות על העגלה הרוסית, הן משום שהשפעתה הגוברת של רוסיה חותרת תחת הנוכחות האמריקנית באזור, והן בשל תמיכתה של וושינגטון במפלגת האיחוד הדמוקרטי (ה-PYD) הכורדית בצפון סוריה. לאחר ששיקמה את היחסים עם מוסקבה בעקבות המשבר שליווה את הפלת מטוס הקרב הרוסי בנובמבר 2015, יצאה תורכיה במבצע “מגן הפרת” ובמבצע “ענף זית” והצליחה להשתלט על חלקים מסוריה, למרות מחאותיה של ארצות הברית. אנקרה העניקה גם תמיכה פוליטית, כלכלית וצבאית לצבא הסורי החופשי (FSA) וסייעה לו בכיבוש הקנטונים ג’ראבולוס ועפרין. בעקבות הסכם סוצ’י, שנחתם עם רוסיה ב-18 בספטמבר, אף החלה תורכיה לפעול כנותנת החסות במרחב אידליב תוך שהיא מונעת מתקפה צבאית על מובלעת מורדים זו.

תורכיה מבקשת לחזק את השפעתה גם ברצועת עזה באמצעות הפעלת “עוצמה רכה” דרך סוכנות הסיוע הממשלתית TIKA (Turkish International Cooperation and Development Agency). במסגרת המאמצים לשיקום הרצועה, ארגוני סיוע לא-ממשלתיים וגופי ממשל תורכיים מעבירים כספי פיצויים וסיוע הומניטרי לעזה דרך נמל אשדוד. בנוסף, תורכיה מעבירה לעזה תמיכה כספית, סכום שהסתכם ב-200 מיליון דולר בין השנים 2014 ל-2017.14 בימים אלה תורכיה תומכת גם במאמצי הפיוס בין הרשות הפלסטינית לחמאס, אם כי אין זה סוד שליבה של אנקרה נוטה אל החמאס.

אנקרה מייחסת חשיבות רבה לשליטה בלוב בשל מיקומה לחוף הים התיכון, ולאחר נפילתו של הקולונל מועמר אל-קד’אפי תמכה אנקרה במועצת המעבר הלאומית (ה-National Transitional Council) והייתה המדינה הראשונה שהכירה בה כנציגתה הבלעדית של לוב כולה. על מנת לחזק את השפעתה בלוב שלחה תורכיה גם סיוע הומניטרי, אם כי זה הופסק בהמשך בשל מורכבויות ביטחוניות.15

על מנת לחזק עוד יותר את השפעתה במזרח הים התיכון תורכיה מבקשת ליצור ראשי גשר בצמתים אסטרטגיים שיאפשרו לה להרחיב את פעילותה מעבר לאזור. שנת 2017 מהווה ציון דרך בהיבט זה, שכן אז הצליחה תורכיה ליצור את “המשולש התורכי” עם חנוכתם של בסיסים צבאיים חדשים בקטאר, בסומליה ובסודאן.16 צעד נועז זה מתפרש על ידי תורכים רבים כמסר ברור למצרים ולישראל: אם תפגע אחת מהן בזכות המעבר בתום לב (Innocent Passage) של כלי שיט תורכיים בתעלת סואץ או במפרץ עקבה יספק הבסיס בסודאן לתורכיה את כל האמצעים הדרושים כדי להעניש את יריביה.17

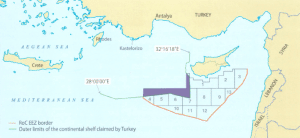

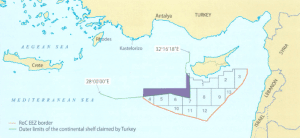

לתורכיה, שכאמור אינה חתומה על אמנת הים של האו”ם, יש חוק משלה להסדרת האזורים הימיים. אף כי חוק זה קובע כי תחום המים הטריטוריאליים בים האגאי משתרע למרחק של 6 מייל ימי (כ-11 ק”מ) מקו החוף, בים התיכון ובים השחור קבעה אנקרה את קו הגבול במרחק של 12 מייל (כ-22 ק”מ). נוכח קרבתם של האיים היווניים בים האגאי לאדמת תורכיה, התביעה היוונית למים טריטוריאליים ברוחב של 12 מייל היא בבחינת קזוס בלי מנקודת המבט של אנקרה. יתר על כן, תורכיה טוענת כי האיים היווניים הם חלק מן המדף היבשתי התורכי, ובמילים אחרות שלאיים אלה אין מדף יבשתי משלהם. בהתאם לכך, אנקרה מציעה לשרטט קו חציוני לאורך נקודת האמצע בין החלקים היבשתיים של שתי המדינות, מתווה שיהפוך את האיים היווניים למובלעות יווניות בתוך המדף היבשתי התורכי.18 המתיחות בין שתי המדינות סביב סוגיה זו נמשכת גם היום. ב-1996 הביאה המתיחות את שתי המדינות אל סף מלחמה סביב איי אימיה/קרדק הבלתי מיושבים, ובשנים האחרונות הביע ארדואן ערעור גלוי על תקפותו של הסכם לוזאן משנות העשרים של המאה הקודמת, המתווה את גבולות תורכיה, ומכאן גם את הסטטוס-קוו הטריטוריאלי בים האגאי.

המחלוקת היוונית-תורכית על המדף היבשתי בים האגאי חרגה והתפשטה גם לאגן הים התיכון, והגבול הימי בין תורכיה היבשתית לרודוס, כמו גם לאי יווני קטן נוסף בשם קסטלוריזו/מאיס, הקרוב מאוד לחוף התורכי בדרום, הפך למוקד מתיחות בין שתי המדינות. הממשל התורכי מבקש לצמצם באופן ניכר את תחום המים הטריטוריאליים של יוון ברודוס (ר’ מפות 3 ו-4), ואנקרה אף הכריזה על קסטלוריזו כמובלעת יוונית במימי תורכיה (ר’ מפה 4). יוון, לעומת זאת, תובעת אזור מים טריטוריאליים ומים כלכליים רציף, בניסיון להרחיב באופן דרמטי את ריבונותה במזרח הים התיכון באמצעות הבלטת חשיבותו של הרצף הגאוגרפי בין האי קסטלוריזו לשאר האיים היווניים (ר’ מפה 3).19

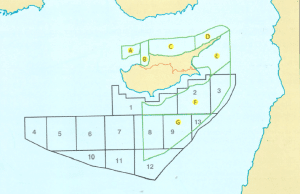

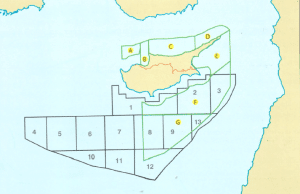

המתיחות בנושא הטריטוריאלי בים התיכון אינה מוגבלת לאיים רודוס וקסטלוריזו, והיא מגיעה עד קפריסין. למרות היותה שכנה של קפריסין התורכית (ה-KKTC, ר”ת של הרפובליקה התורכית של צפון קפריסין בתורכית, ובאנגליתTRNC ), שחתמה עם אנקרה על הסכם תיחום דו-צדדי במענה לדרישותיה, אנקרה טוענת שקפריסין הכריזה על בלוקים 1-4-5-6-7 כחלק מהמדף היבשתי שלה (ר’ מפה 1). בגיבוי לעמדתה ביחס לבלוקים שקפריסין התורכית תובעת לעצמה אימצה תורכיה שפה לוחמנית כלפי ניקוסיה, והיא מזהירה בעקביות כי היא נחושה בדעתה לנקוט בכל האמצעים הדרושים כדי להגן על זכויותיה הריבוניות.20 בפועל, תורכיה נוקטת פעולות ימיות שמטרתן להפריע לעבודתן של ספינות המחקר באזור זה, ויעדן הסמוי – להבריח משקיעים מערביים.

בנוסף היא עורכת חיפושי גז עצמאיים משלה. במסגרת זו החליפה תורכיה את ספינת המחקר הוותיקה פירי ראיס בספינה המודרנית ברברוסה ח’יר א-דין פאשה, שהושקה לראשונה במימי מזרח הים התיכון ב-21.2017 במקביל היא פועלת גם להעצמת הזרוע הימית שלה, וכחלק מפרויקט הנשק הלאומי כבר השיקה ארבע ספינות מלחמה מצוידות היטב במסגרת תוכנית ספינות הקרב, מילגם (Milgem).22 ה-TC-G Heybeliada, שנכנסה לשימוש מבצעי ב-2011, מייצגת בצורה המוחשית ביותר את המדיניות התורכית. הספינה מוכרת גם בשם “ספינת הרפאים” בשל יכולתה להתחמק מזיהוי מכ”ם. ה-TC-G Heybeliada, שכבר הפגינה את יכולותיה, עברה לייצור סדרתי, וב-2013, 2016, ו-2017, בהתאמה, רכשו הכוחות המזוינים של תורכיה את ה-TC-G Büyükada,23 ה-TC-G Burgazada24 וה-.TC-G Kınalıada25

ב-18 באוקטובר 2018 החלו הספינות התורכיות המאובזרות הללו להפגין נוכחות במזרח הים התיכון, כאשר פריגטה יוונית ניסתה למנוע מספינת מחקר תורכית לנוע באזור השנוי במחלוקת שממערב לקפריסין, מה שגרם להתפרצות “קרב חתולים ימי” בין הצי היווני לצי התורכי.26 נוסף למאמצי הצי היווני להגביל את הפעילות התורכית באזור ניסתה ממשלת יוון להגביר את הלחץ על תורכיה לקראת ועידת הפסגה של מדינות הבלקן שנערכה בוורנה שבבולגריה בנובמבר 2018. לצד בולגריה, רומניה וסרביה הוסיפה אתונה למשתתפות בפסגה גם את ישראל ליצירת משוואה מזרח ים-תיכונית חדשה, מתוך מטרה להגביר את הלחץ על אנקרה.27 כפי שניתן היה לצפות, ממשלת ארדואן לא הגיבה בשתיקה. ב-4 בנובמבר, במהלך טקס שנערך במספנת חיל הים באיסטנבול, איים ארדואן בגלוי על יוון ועל שותפותיה במזרח הים התיכון, תוך שהוא נוקט רשמית קו ניצי נגד הקואליציה הזאת: “לעולם לא נקבל את הניסיונות לבצע מחטף על המשאבים הטבעיים במזרח הים התיכון תוך הדרת ארצנו והרפובליקה התורכית צפון קפריסין (KKTC). אין לנו שום שאיפות [ביחס] לשטחיהן של [מדינות] אחרות. מי שמתעלם מתורכיה וחושב כי הוא יכול לנקוט צעדים חד-צדדיים במזרח הים התיכון ובים האגאי, החל סוף סוף להבין שהוא עושה טעות גדולה. [כמו עם] הטרוריסטים שהבסנו בסוריה, גם כאן לא ניתן לשודדי הים לפעול נגדנו”.28

סכסוך האנרגיה בין קפריסין לתורכיה

מאז הפלישה התורכית לקפריסין ב-1974 האי מחולק בפועל לשתי מדינות נפרדות: קפריסין היוונית בדרום, ומדינת קפריסין התורכית, או שטח הכיבוש התורכי (המאוכלס כיום גם במתיישבים מהיבשת) בצפון. ממשלת יוון הקפריסאית הקיימת, המכונה רשמית “הרפובליקה של קפריסין”, נחשבת לבעלת הסמכות הלגיטימית בכפוף למשפט הבינלאומי, ואילו הרפובליקה התורכית של צפון קפריסין היא ישות נטולת הכרה בינלאומית (למעט באנקרה). אולם למרות היותה נטולת הכרה רשמית, מאז 1983 קפריסין התורכית פועלת כמדינה ריבונית בצפון האי בזכות נוכחותו של הצבא התורכי (ה-TSK).

הממשלה הקפריסאית היוונית, המוכרת להלכה כממשל הלגיטימי היחיד באי, ביקשה לחזק את מעמדה באמצעות חתימת הסכמי תיחום להגדרת גבולות המים הכלכליים והגבולות הימיים שלה בדרום-מזרח הים התיכון. ב-1964 תבעה לעצמה קפריסין, כאי, את 12 המייל הימיים הטריטוריאליים שלה, וב-1988 אישרה את אמנת האומות המאוחדות לחוק הים (UNCLOS). בהכירה בפוטנציאל העצום הטמון בגז הטבעי חתמה קפריסין בפברואר 2003 על הסכם עם מצרים על גבול המים הכלכליים, ובעקבותיו הגיעה להסכמים דומים גם עם לבנון ב-2006 ועם ישראל ב-2010. לאחר הבטחת גבולותיה הכלכליים מדרום ומדרום-מזרח חילקה קפריסין את האזור הכלכלי הבלעדי שלה ל-13 בלוקים, והעניקה לחברת נובל אנרג’י את הזכות להפקת גז טבעי. ההתפתחות המשמעותית ביותר אירעה בדצמבר 2011, אז הכריזה נובל אנרג’י על גילוי גז טבעי בבלוק 12 – הוא מאגר הגז אפרודיטה, ולאחרונה נוספה לכך הודעת EXXON על תגליות בבלוק 10.

על מנת למנוע הידרדרות נוספת ביחסיה עם תורכיה ועם ה-KKTC נמנעה קפריסין ממיפוי החלקות הסמוכות לחופיו הצפוניים של האי במפת הגז הטבעי שלה, אלא שלאור המחלוקת המתמשכת ביניהן ותביעותיהן המתחרות לבלוקים 1, 4, 5, 6 ו-7 תורכיה מסרבת להכיר בהסכמי המים הכלכליים של קפריסין. לטענת אנקרה בלוקים אלה ממוקמים על המדף היבשתי של תורכיה.

אולם כאב הראש של קפריסין אינו מוגבל לתורכיה לבדה. בתגובה למפת החלקות ששרטטה קפריסין פרסמה ה-KKTC מפה משלה, ולפיה בלוקים “F” ו-“G” של ה-KKTC חופפים לבלוקים 1, 2, 3, 8, 9, 12 ו-13 של קפריסין היוונית. לפיכך הבלוקים היחידים של קפריסין היוונית שאינם נתונים במחלוקת על פי טענות התורכים הם בלוקים 10 ו-11. על מנת להימנע מהחרפת המתח בין המדינות נמנעה קפריסין היוונית מהוצאת הבלוקים הנתונים במחלוקת למכרז בינלאומי, אולם ניקוסיה טרם הכירה בתביעות ה-KKTC לחלקות השנויות במחלוקת.

נוכח תביעותיה של ה-KKTC לחופו הדרומי של האי ניתן להסיק בבטחה שטענותיה המרכזיות נוגעות לסוגיות של ריבונות ולא של חלוקת העושר. כישות המהווה חלק מהאי, קפריסין התורכית מבקשת הכרה בינלאומית בתביעתה לנתח שווה ממשאביו הטבעיים.29 אלא שה-KKTC, שתביעתה זו נשענת על החוק הבינלאומי, מוחזקת כמפרה עיקרית של אותו חוק עצמו נוכח כיבוש האי דה פקטו החל משנת 1974. על מנת לבסס את עמדתה מול קפריסין חתמה ה-KKTC ב-2011 על הסכם תיחום מדף יבשתי עם תורכיה המעניק לחברת הנפט התורכית (TPAO) את הסמכות הסופית לביצוע מחקרים סייסמיים באזור שבין תורכיה לקפריסין התורכית. אקט זה נועד, ללא ספק, לחתור תחת ריבונותה של קפריסין על חלק זה של האי.30

עמדת האיחוד האירופי

מאחר שהיעד של חלק ניכר מהגז המזרח ים-תיכוני הוא אירופה, ולאור העובדה שגם יוון וגם קפריסין חברות באיחוד האירופי, מן הראוי לבחון את צריכת האנרגיה והתלות האנרגטית של האיחוד האירופי בייבוא גז. האיחוד האירופי מייבא יותר ממחצית מכלל האנרגיה שהוא צורך, עם תלות גבוהה במיוחד בייבוא נפט גולמי (90%) וגז טבעי (69%). חשבון הייבוא הכולל עולה על מיליארד אירו ליום.31

בשל צורכי מגזר התחבורה, נפט הוא עדיין הדלק החשוב ביותר שהאיחוד האירופי צורך, וב-2017 היווה 37.1% מסך הדלקים. השימוש בגז טבעי הראה עלייה קלה, 1.2%, במהלך אותה תקופה, והגיע ל-%,32 23 ואילו השימוש בפחם ירד בצורה דרסטית בעשור האחרון. ב-2007 צרך האיחוד האירופי 372.9 מיליון טון פחם, ועד 2017 צנחה הצריכה ל-296.4 מיליון טון. גז נתפס היום כחומר דלק חלופי לפחם בעולם בכלל, ובאירופה בפרט.33

לפני גילויי הגז במזרח הים התיכון היו לאיחוד האירופי שני מסדרונות גז עיקריים: קווי הגז הרוסיים החוצים את הים הבלטי לאירופה דרך גרמניה, והגז הנורבגי. פרט לשני מסדרונות אלה, הפעילים עדיין, גם אלג’יריה, לוב, ניגריה וקטר נחשבות מקור חלופי לגז טבעי. על פי EU Energy in Figures: 2017 Statistical Pocket Book, ב-2015 ייבא האיחוד האירופי 37% מהגז הטבעי שלו מרוסיה, ואחריה נורבגיה עם 32.5%.34 הצינור הישראלי-קפריסאי-יווני-איטלקי המתוכנן במזרח הים-התיכון, שעליו חתמו שרי האנרגיה של ארבע המדינות מזכר הבנות בדצמבר 2017,35 יקטין את התלות של האיחוד האירופי ברוסיה. גם אם יוכל הצינור להעביר לאירופה 16 מיליארד מ”ק גז בשנה החל משנת 2025, הוא עדיין ייתן מענה רק ל-5% מהצריכה השנתית. ובכל זאת, האיחוד האירופי יוכל בהדרגה לצמצם את 100 ממ”ק הגז שהוא קונה מרוסיה מדי שנה.36

השיח הציבורי בתורכיה בנושא מזרח הים התיכון

בעקבות מלחמת העולם הראשונה ומלחמת העצמאות התורכית (המלחמה נגד הפולש היווני) איבדה תורכיה חלקים ניכרים משטחה. בעוד שב-1913 שלטה האימפריה העות’מאנית על חופי הים האדריאטי, ב-1919 כבר הייתה בירת האימפריה, איסטנבול, נתונה תחת כיבוש. הסכם סוור (1920) הסדיר את אובדן השטח הזה ועורר טראומה לאומית, “תסמונת סוור”, העוברת מדור לדור37 ומציירת את מעצמות המערב כאויבות פוטנציאליות המבקשות להחליש או לבתר את תורכיה. חוסר האמון כלפי המערב הוליד תאוריות קונספירציה לרוב, כמעט ביחס לכל מחלוקת בין תורכיה למערב.

נוסף לתסמונת סוור, הנאו-עות’מאניות שהחלה לצמוח בתקופת שלטונו של תורגוט אוזאל זכתה לתנופה משמעותית תחת ארדואן, שטיפח השקפת עולם זו והעצים את “המאבק הנצחי בין הצלב לסהר”.38 רטוריקה מסוג זה הביאה רבים מהתורכים להתייחס לאירועים פוליטיים מקומיים ובינלאומיים שונים כאל מהלכים המכוונים נגד תורכיה במשחק מורכב של שחמט המתנהל כבר מאות שנים.

בהתחשב בתפיסת עולמה זו ראתה תורכיה בדחיית תוכנית השלום של ענאן לאיחוד קפריסין ב-2004, ובצירופה של קפריסין לאיחוד האירופי בשנה שלאחר מכן, צורה של השפלה דיפלומטית מכוונת. זאת ועוד, תגליות הגז של מצרים, ישראל וקפריסין במזרח הים התיכון, צמיחתה של מדינה כורדית דה פקטו בצפון עיראק ובצפון סוריה ותמיכתה של ישראל בממשלה האזורית של כורדיסטן (ה-KRG) וביוון נתפסו אף הן כחלק בלתי נפרד מ”המשחק הגדול”. התעניינות גוברת של חברות נפט בינלאומיות במיזם זה, ביניהן נובל אנרג’י, החברה הרוסית גזפרום וחברת ENI האיטלקית (שרבים מהתורכים רואים בה זרוע של הוותיקן) הולידה בקרב הציבור התורכי הלך רוח הסובב סביב תאוריות קונספירציה שונות ומשונות.39 תפיסה זו, שלפיה תורכיה נמצאת תחת איום מתמיד, הפעילה באופן בלתי מפתיע את האסטרטגיה הישנה-חדשה של “גיוון הבריתות”. במילים אחרות, במקום להסתמך אך ורק על המערב תורכיה מבקשת לחזק את קשריה עם רוסיה וסין, כפי שעשתה אחרי הפלישה לקפריסין ב-1974. הואיל והיחסים עם ארצות הברית, ישראל והאיחוד האירופי מתוחים, האינטרס שלה בגיוון בנות בריתה דוחק את תורכיה לכיוון ציר רוסיה-סין, ובמידה מסוימת גם לחיזוק הקשרים עם איראן.40

יש לציין שבחירה אסטרטגית זו באה לראשונה לידי ביטוי ב-2010, אז הייתה תורכיה אחת משתי המדינות היחידות (לצד ברזיל) שהצביעו נגד החלטת מועצת הביטחון של האו”ם להטיל סנקציות נוספות על איראן.41 סימן משמעותי נוסף למגמה זו נחשף בעקבות פרסום דו”ח ועדת פאלמר על אירועי משט המרמרה במאי 2010, שבמסגרתו התעמתו אנשי הארגון התורכי IHH42 עם צה”ל בניסיון לשבור את המצור הימי שהטילה ישראל על רצועת עזה. אנקרה הטילה אז סנקציות על ישראל, ושר החוץ אחמד דוואטולו שלח מסר ישיר לישראל כשהורה לחיל הים התורכי להבטיח את “זכות השיט” של תורכיה במזרח הים התיכון. 11 ימים בלבד מאוחר יותר הוסיפה תורכיה וחיבלה במתכוון בקשרים עם ישראל, כאשר הודיע הצבא התורכי כי הצטייד במערכת זיהוי עמית-טורף (IFF)43 לאומית משלו שבאפשרותה לזהות את כוחות הצבא הישראליים והיווניים כגורמים עוינים,44 במקום בגרסת נאט”ו המזהה באופן אוטומטי את כל מטוסי מדינות נאט”ו כ”ידידים”. באופן בלתי נמנע חיזקו צעדים אלה את האינטרס הישראלי בהידוק היחסים עם יוון וקפריסין.

תורכים רבים פירשו את ההתקרבות בין המדינות כתחבולה של יוון שמטרתה להשתמש בישראל כמגן מפני תורכיה בקפריסין. השמועות שישראל עומדת להקים על האי בסיס צבאי45 ולערוך תרגילים צבאיים משותפים באזורים ההרריים שלו46 הביאו רבים מהתורכים לראות בישראל איום ביטחוני מרכזי. תוצאות סקר שערכה אוניברסיטת Kadir Has (KHU) באיסטנבול מאששות מגמה זו: בשנת 2018 ראו התורכים את ארצות הברית וישראל כמקורות האיום הגדולים ביותר על הביטחון הלאומי, בשיעור של 60.2% ו-54.4%, בהתאמה.47

תקריות האוויר המתרחשות עדיין בשמי הים האגאי או מעל מימי מזרח הים התיכון בין מטוסים תורכיים ויווניים מוסיפות דלק למדורה ברמה הבין-אישית. במאי 2017, למשל, הודלפו בכל העולם צילומים המראים את צוות הספינה התורכית ברברוסה ח’יר א-דין פאשה משמיע לצי של קפריסין היוונית את המארש הצבאי העות’מאני המפורסם “Ceddin Deden”, ועוררו סערה בתקשורת התורכית וברשתות חברתיות. תקרית זו מהווה אינדיקציה לעליית הלאומיות התורכית ולתפיסת “תורכיה המאוימת לעולם”.48

בעשור הראשון של שנות האלפיים התמקדו התרבות הפופולרית והקולנוע התורכי בחזיונות בדבר מלחמת אמריקה-תורכיה, ואילו בשנים האחרונות התחלפה המלחמה עם ארצות הברית במלחמה תורכית-ישראלית פוטנציאלית, מלחמה הנידונה בגלוי כאפשרות ממשית באותן מדיות. אף כי חלק ממוצרי התרבות הפופולרית, כמו הסרט “עמק הזאבים – פלסטין”, מתמקדים ישירות בישראל כזירת העימות, אחרים, ביניהם סרטוני יוטיוב49 ורומנים כמו “מבצע דוד” (Davut Harekatı)50 מאת סדאט פקדמיר, מתייחסים אל מזרח הים התיכון כאל נקודת החיכוך הסבירה ביותר.

על פי תרחישי מלחמה אלה, תורכיה וישראל ייכנסו ללחימה בעקבות הסלמת המצב במזרח הים התיכון. בהתחשב בעוצמתה הצבאית של ישראל התורכים אומנם יספגו נפגעים רבים, אולם באופן בלתי מפתיע תסתיימנה כל המערכות הפנטסטיות הללו בניצחונות תורכיים מכריעים שיכללו אפילו את שחרור ירושלים מה”כיבוש” הישראלי.

חילוקי הדעות הנוכחיים במזרח הים התיכון עלולים אפוא להוביל להעצמת הלאומיות התורכית כפי שהיא באה לידי ביטוי בקפריסין, בזיקה לאסלאם פוליטי שחלק מסוכניו אכן משתעשעים בפנטזיות על שחרור ירושלים מהמדינה היהודית.

מסקנות

ממשלת ארדואן עושה שימוש במדיניות החוץ התורכית הן כדי לחזק את תמיכתה הציבורית מבית והן כדי להרתיע ארבע משכנותיה למזרח הים התיכון – יוון, ישראל, קפריסין ומצרים – ממימוש שאיפותיהן באזור. דבריו של שר החוץ התורכי, מבלוט צ’בושואלו, עולים בקנה אחד עם מגמה זו. צ’בושואלו הבהיר כי תורכיה תמשיך לנקוט את כל אמצעי הזהירות הנדרשים כדי להגן על האינטרסים של תורכיה ושל קפריסין התורכית נוכח התרגילים הצבאיים הנערכים במזרח הים התיכון.51 מנגד הראה לאחרונה הנשיא ארדואן סימנים לעניין בנורמליזציה אפשרית עם מצרים וישראל, תוך שימת דגש על היותה של תורכיה מסלול הייצוא הכדאי ביותר מבחינה כלכלית, בהתחשב בעלויות הגבוהות הכרוכות בהקמת הצינור החלופי שמתכננות הארבע בשיתוף עם איטליה.52 דבריו של ארדואן מצביעים על כך שתורכיה עדיין מעוניינת לשמש גשר לצינור המזרח ים-תיכוני לאירופה.

יוון, ישראל, קפריסין ומצרים, מצידן, ממשיכות להתקדם משמעותית ללא תורכיה. בהקשר זה, בעקבות פסגה של המנהיגים במאי 2018 בניקוסיה,53 ביקרו שרי החוץ של יוון וקפריסין בירושלים על מנת לקדם את פרויקט הצינור. הפגישה המשולשת השנייה התנהלה לאחר שהודלף לעיתונות דו”ח מסווג של משרד החוץ הישראלי שלפיו ייצוא גז ישראלי דרך תורכיה אינו נתפס עוד כצעד נבון מכיוון שהממשל התורכי הינו “שחקן לא יציב ומסוכן”.54

לאחרונה טוענים כלי התקשורת כי שתי המדינות מקיימות שיחות חשאיות במטרה לשקם את היחסים ביניהן, מגעים שיסללו ככל הנראה את הדרך לחילופי שגרירים.55 למרות השמועות המעודדות הללו, דבריו האחרונים של ראש הממשלה נתניהו על היחסים עם תורכיה ועם ארדואן, דהיינו שהוא אינו רואה שום אור בקצה המנהרה בגלל יחסו הבלתי צפוי של הנשיא ארדואן, משקפים את האמת המרה: נורמליזציה אמיתית היא עדיין בגדר שאיפה רחוקה.56

הפריזמה המדינית הנאו-עות’מאנית שתורכיה רואה דרכה את שכנותיה מונעת ממנה, ככל הנראה, לראות את מכלול ההיבטים האסטרטגיים, המשפטיים, הכלכליים והחברתיים במשוואה המזרח ים-תיכונית. אף כי הריאליזם המדיני שכינס את ארבע המדינות יחד יאלץ גם את תורכיה לנרמל את יחסיה עם ישראל ועם מצרים, אנקרה לא נקטה עדיין צעדים משמעותיים בכיוון והנשיא ארדואן ממשיך מבקר אותן ללא הרף, בעיקר כדי לזכות באישור ציבורי מבית. דבריו הקשים של ארדואן והניסיונות לדה-לגיטימציה גורמים ללא ספק למשברי אמון קשים בין קהיר וירושלים לבין תורכיה. חוסר האמון, בשילוב עם תגליות הגז, קירב בין שתי המדינות ודחף אותן לזרועותיהן של קפריסין ויוון, שגם להן חילוקי דעות חריפים עם תורכיה.

בכל הנוגע לחילוקי הדעות עם תורכיה ידן של הארבע על העליונה הן במישור האסטרטגי, הן במישור המשפטי והן במישור הכלכלי. יתרון זה עשוי לתת בידיהן את היכולת לממש את הפרויקט השאפתני שלהן, אם יהיה ביכולתן לגייס את הכספים הדרושים ליישום המיזם.

תורכיה הגיעה לצומת דרכים חדש שבו עליה להחליט: האם להמשיך לחתור ל”בדידות מזהרת” (וריאציה על המונח הבריטי המקורי מהמאה ה-19 “בדידות מזהירה”), דוקטרינת חוץ שהפכה שם נרדף למשחקי ה”הליכה על הסף” של תורכיה, או אולי לבקש נורמליזציה אמיתית עם ארבע שכנותיה. החזרת האמון בין המדינות תחייב נורמליזציה אמיתית, וזו בתורה תחייב את תורכיה להפסיק את ההתנגחות בישראל ובמצרים במרחב הפוליטי.

אם ישראל ומצרים אכן יצליחו לעבוד יחד ולייצב את המשבר בעזה, למרות הניסיונות החתרניים של רמאללה, יהיה לארדואן קל יותר להסביר לציבור התורכי את השינוי הפתאומי במדיניות או בגישה כלפי שתי המדינות, ואם אווירה כזו תישמר ותהפוך למדיניות יציבה, הרי שבסופו של דבר היא תסלול את הדרך לשיתוף פעולה אמיתי בנושא הגז מבלי להוציא מהמשוואה אף אחת מהשחקניות האזוריות. פריצת דרך כזו עשויה, לפחות להלכה, להביא להשגת הסכם שלום סופי בקפריסין, דבר שיפתח פתח לשגשוג האזור כולו. לישראל יש אינטרס ברור להשאיר דלת זו פתוחה, ולו למראית עין.

עם זאת, סביר מאוד להניח שמדיניות החוץ הנאו-עות’מאנית הנוקשה של תורכיה, המונעת על-ידי מתחים דיפלומטיים בעיקר מול מדינות לא-מוסלמיות, תאפיל על הסיכוי לשגשוג במזרח הים התיכון. יכולתו של ארדואן להפוך את המתחים הדיפלומטיים ואת הסלמת היחסים לתמיכה ציבורית בלתי מעורערת מבית אל מול המשבר הכלכלי מעודדת אותו לדבוק בגישה זו, ולגבש מורשת המבוססת על עימות בין הצלב (ומגן דוד) לסהר.

אם לא תעשה אנקרה פניית פרסה בלתי צפויה, סביר להניח שהאיבה המתגברת של תורכיה כלפי צינור הגז המזרח ים-תיכוני תשנה את התוואי כולו ותהפוך את מצרים ליעד הגז של קפריסין וישראל בדרך לייצוא לאירופה כגט”ן שיועבר בספינות, ולא בצינורות. בתרחיש כזה, אירופה לא תוכל להטיל את משקלה נגד תורכיה משום שאנקרה תוכל להשתמש במשבר הפליטים הסורי המתמשך כקלף ניצחון מול האיחוד. לכן בסופו של דבר, תורכיה היא זו שתצטרך להחליט האם לקחת חלק במיזם האזורי המשגשג הזה כשותפה אמיתית, או לפעול נגדו מבלי להשיג דבר ממשי פרט להתשה נוספת.

[1] Simon Henderson, “Cyprus Aims to Export Gas via Egypt,” The Washington Institute, September 21, 2018, https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/view/cyprus-aims-to-export-gas-via-egypt [Accessed: October 17, 2018]

[2] Ceyhun Çiçekli, “DoğuAkdeniz’de Şer İttifakı,” Yeni Şafak, October 9, 2018, https://www.yenisafak.com/hayat/dogu-akdenizde-ser-ittifaki-3400890 [Accessed: October 17, 2018]

[3] R. Suryamurthy, “Shale lures ONGC to quit block,” The Telegraph, India,https://www.telegraphindia.com/1110221/jsp/business/story_13611726.jsp [Accessed: September 5, 2018]

[4] Molly Lempriere, “Zohr gas field: Egypt’s megaproject holds a lot of promise,” Offshore Technology, https://www.offshore-technology.com/features/zohr-gas-field-egypts-megaproject-holds-lot-promise/ [Accessed: September 5, 2018]

[5] Ayla Gürel, Fiona Mullen and Harry Tzimitras, “The Cyprus Hydrocarbons Issue: Context, Positions and Future Scenarios,” Prio Cyprus Center, PCC Report 1, 2013, pp. 1-5

[6] Moises Naim, “The Mediterranean Surprise,” Eniday, https://www.eniday.com/en/human_en/eastern-mediterranean-sea-of-gas/ [Accessed: November 21, 2018]

[7] Israeli Gas Opportunties, Israeli Ministry of Energy, http://archive.energy.gov.il/Subjects/OilSearch/documents/israeli%20gas%20opportunitties.pdf [Accessed:March 26, 2019[

[8] Aphrodite Gas Field, https://www.offshore-technology.com/projects/aphrodite-gas-field/ [Accessed: October 17, 2018]

[9] Israel Selling Gas to Egypt: Mark of the Real New Middle East, Haaretz, September 27, 2018, https://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/.premium-israel-selling-gas-to-egypt-mark-of-the-real-new-middle-east-1.6512663 [Accessed: October 17, 2018]

[10] Hay Eytan Cohen Yanarocak, “Turkish – Israeli Reconciliation: The End of ‘Precious Loneliness’?” Tel Aviv Notes, Volume 10, Number 11 June 26, 2016, https://dayan.org/content/turkish-israeli-reconciliation-end-precious-loneliness [Accessed: November 5, 2018]

[11] Kıbrıs: Doğal gaz çözümü hızlandırır mı??, BBC Türkçe, July 18, 2014, https://www.bbc.com/turkce/haberler/2014/07/140718_kibris_gaz [Accessed: September 17, 2018]

[12] Alan Makovsky, “The Cyprus factor in Turkish-Israeli normalization,” Turkeyscope Insights on Turkish Affairs, Vol. 1, No. 2, December 2016 https://dayan.org/content/cyprus-factor-turkish-israeli-normalization [Accessed: September 17, 2018]

[13] “Küresel enerji oyunundaTürkiye’nin pozisyonu ve Doğu Akdeniz,” Anadolu Ajansı, June 28, 2018, https://www.aa.com.tr/tr/analiz-haber/kuresel-enerji-oyununda-turkiye-nin-pozisyonu-ve-dogu-akdeniz/1189968 [Accessed: September 17, 2018]

[14] “Türkiye – Filistin Siyasi İlişkileri,” Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, http://www.mfa.gov.tr/turkiye-filistin-siyasi-iliskileri.tr.mfa [Accessed: October 17, 2018]

[15] “Türkiye – Libya Siyasi İlişkileri,” Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, http://www.mfa.gov.tr/turkiye-libya-siyasi-iliskileri.tr.mfa [Accessed: October 17, 2018]

[16] “Türk Üçgeni,” Vatan, December 27, 2017, http://www.gazetevatan.com/turk-ucgeni–1129823-gundem/ [Accessed: October 17, 2018]

[17] Kıyam – Sevakin Adası Neden Önemli? Çok Şaşıracaksınız – İsrail’in Planına Denizaşırı Müdahale Ettik, YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gjB-L2_QRZY [Accessed: October 17, 2018]

[18] TC Dışişleri Bakanlığı, “Başlıca Ege Denizi Sorunları,” http://www.mfa.gov.tr/baslica-ege-denizi-sorunlari.tr.mfa [Accessed: September 20, 2018]

[19] Ayla Gürel, Fiona Mullen and Harry Tzimitras, “The Cyprus Hydrocarbons Issue: Context, Positions and Future Scenarios,” Prio Cyprus Center, PCC Report 1, 2013, pp. 26-29

[20] Ayla Gürel, Fiona Mullen and Harry Tzimitras, “The Cyprus Hydrocarbons Issue: Context, Positions and Future Scenarios,” Prio Cyprus Center, PCC Report 1, 2013, pp. 51-54

[21] “Barbaros Hayrettin Paşa sismik gemisi Akdeniz’e iniyor,” Akşam, April 23, 2017, https://www.aksam.com.tr/ekonomi/barbaros-hayrettin-pasa-sismik-gemisi-akdenize-iniyor/haber-617243 [Accessed: September 20, 2018]

[22] Hay Eytan Cohen Yanaocak, “No Strings Attached: Turkey’s Arms Projects as a Foreign Policy Tool,” Turkeyscope Insights on Turkish Affairs, Vol. 1, No. 2, December 2016, https://dayan.org/content/no-strings-attached-turkey%E2%80%99s-arms-projects-foreign-policy-tool [Accessed: September 20, 2018]

[23] “Milli gemimiz suya indirildi,” Yeni Şafak, September 27, 2013, http://www.yenisafak.com/gundem/milli-gemimiz-suya-indirildi-569041 [Accessed: October 17, 2018]

[24] “Cumhurbaşkanı Burgazada Korvetini Denize İndirdi, Kınalıada’nın saç kesimini yaptı,” Haberler, June 18, 2016, http://www.haberler.com/cumhurbaskani-burgazada-korvetini-denize-indirdi-8539907-haberi/ [Accessed: October 17, 2018]

[25] “MİLGEM’dekritikadım… TGC Kınalıadadenizeindirildi,” Cumhuriyet, July 3, 2017, http://www.cumhuriyet.com.tr/haber/turkiye/773036/MiLGEM_de_kritik_adim…_TGC_Kinaliada_denize_indirildi.html [Accessed: October 17, 2018]

[26] “Yunanistan Barbaros gemisini taciz etti,” CNN Türk, October 18, 2018, https://www.cnnturk.com/son-dakika-dogu-akdenizde-gerginlik [Accessed: November 4, 2018]

[27] “Tsipras-Netanyahu discuss EastMed pipeline during Balkan summit,” Ahval, November 3, 2018, https://ahvalnews.com/eastern-mediterranean/tsipras-netanyahu-discuss-eastmed-pipeline-during-balkan-summit [Accessed: November 4, 2018]

[28] “Son dakika… Cumhurbaşkanı Erdoğan’dan flaş açıklamalar,” Hürriyet, November 4, 2018, http://www.hurriyet.com.tr/ekonomi/son-dakika-cumhurbaskani-erdogandan-flas-aciklamalar-41008240 [Accessed: November 4, 2018]

[29] Ayla Gürel, Fiona Mullen and Harry Tzimitras, “The Cyprus Hydrocarbons Issue: Context, Positions and Future Scenarios,” Prio Cyprus Center, PCC Report 1, 2013, pp. 45-54.

[30] TC Dışişleri Bakanlığı Basın Açıklamaları, No: 216, 21 Eylül 2011 Türkiye – KKTC Kıta Sahanlığı Sınırlandırma Anlaşması İmzalanmasına İlişkin Dışişleri Bakanlığı Basın Açıklaması, http://www.mfa.gov.tr/no_-216_-21-eylul-2011-turkiye-_-kktc-kita-sahanligi-sinirlandirma-anlasmasi-imzalanmasina-iliskin-disisleri-bakanligi-basin-ac_.tr.mfa [Accessed: September 20, 2018]

[31] “Energy Security Strategy,” European Union, https://ec.europa.eu/energy/en/topics/energy-strategy-and-energy-union/energy-security-strategy [Accessed: August 22, 2018]

[32] “British Petroleum (BP) 2018 Statistical Review of World Energy,” p. 9, https://www.bp.com/content/dam/bp/en/corporate/pdf/energy-economics/statistical-review/bp-stats-review-2018-full-report.pdf [Accessed: August 22, 2018]

[33] “British Petroleum (BP) 2018 Statistical Review of World Energy,” p. 39, https://www.bp.com/content/dam/bp/en/corporate/pdf/energy-economics/statistical-review/bp-stats-review-2018-full-report.pdf [Accessed: August 22, 2018]

[34] EU Energy in Figures 2017 Statistical Pocket Book, (Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2017), p. 26, https://publications.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/2e046bd0-b542-11e7-837e-01aa75ed71a1/language-en/format-PDF/source-search [Accessed: August 22, 2018]

[35] Sonia Gorodeisky, “Israel-Europe gas pipeline MoU signed,” Globes, December 5 2017, https://en.globes.co.il/en/article-israel-europe-gas-pipeline-mou-signed-1001214430 [Accessed: August 22, 2018]

[36] Andrew Rettman, EU Observer, December 6, 2017, https://euobserver.com/energy/140183 [Accessed: August 22, 2018]

[37] Hasan Cemal, Kürtler (Istanbul, Doğan Kitap, 2007) p. 337

[38] “Erdoğan: Haçlı Hilal Savaşı Başladı,” Timeturk, March, 16, 2017 https://www.timeturk.com/erdogan-hacli-hilal-savasi-basladi/haber-534740 [Accessed: September 20, 2018]

[39] Cafer Talha Şeker, DoğuAkdeniz’deki Enerji Rekabetinde İsrail, VatikanveTürkiye’ninKonumu, ORDAF, February 13, 2018, http://ordaf.org/dogu-akdenizdeki-enerji-rekabetinde-israil-vatikan-ve-turkiyenin-konumu/ [Accessed: September 20, 2018]

[40] Cem Gürdeniz, DoğuAkdeniz’de yeni jeopolitik evre, Aydınlık, June 3, 2018, https://www.aydinlik.com.tr/dogu-akdeniz-de-yeni-jeopolitik-evre-cem-gurdeniz-kose-yazilari-haziran-2018 [Accessed: September 20, 2018]

[41] “BM’de Türkiye’nin İran oyu hayır oldu,” Milliyet, June 9, 2010, http://www.milliyet.com.tr/bm-de-turkiye-nin-iran-oyu-hayir-oldu/dunya/dunyadetay/09.06.2010/1248838/default.htm [Accessed: August 22, 2018]

[42] İnsan Hak ve Hürriyetleri ve İnsani Yardım Vakfı – The Foundation for Human Rights and Freedoms and Humanitarian Relief

[43] Identification of Friend and Foe

[44] “İsrail artıkTürk F-16 için ‘dost’ değil,” Sabah, September 13, 2011, https://www.sabah.com.tr/gundem/2011/09/13/israil-artik-turk-f16-icin-dost-degil [Accessed: September 20, 2018]

[45] Ata Atun, “Kıbrıs’ta İsrail’e üs,” Kıbrıs Postası, May 21, 2012, http://www.kibrispostasi.com/c1-KIBRIS_POSTASI_GAZETESI/j97/a15279-Kibrista-israile-us- [Accessed: September 20, 2018]

[46] In mountains and cities of Cyprus, IDF special forces train for war, Times of Israel, December 7, 2017, https://www.timesofisrael.com/in-mountains-and-cities-of-cyprus-idf-special-forces-train-for-war/ [Accessed: September 20, 2018]

[47] “Türk Dış Politikası Kamuoyu Algıları Araştırması: En büyük tehdit ABD ve İsrail,” Anadolu Ajansı, June 16, 2018, https://www.aa.com.tr/tr/turkiye/tu%CC%88rk-dis%CC%A7-politikasi-kamuoyu-algilari-aras%CC%A7tirmasi-en-buyuk-tehdit-abd-ve-israil/1167631 [Accessed: September 20, 2018]

[48] “Barbaros Hayrettin Paşa gemisinden Rumlara ‘mehterli’ cevap,” Hürriyet, May 5, 2017, http://www.hurriyet.com.tr/gundem/barbaros-hayrettin-pasa-gemisinden-rumlara-mehterli-cevap-40448661 [Accessed: September 17, 2018]

[49] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0txFO9Jt6_0 [Accessed: September 17, 2018]

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bsSBdTLGV-s [Accessed: September 17, 2018]

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m1adAT9yOo0&t=174s [Accessed: September 17, 2018]

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UtkuhpEiWmo [Accessed: September 17, 2018]

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6yqpR4vTNrc [Accessed: September 17, 2018]

[50] SedatPekdemir, DavutHarekatı (Istanbul, Yakın Plan, 2015)

[51] “Bakan Çavuşoğlu’ndan ‘hidrokarbon’ açıklaması: Sondajlara başlayabiliriz,” YeniŞafak, September 3, 2018, https://www.yenisafak.com/gundem/bakan-cavusoglundan-hidrokarbon-aciklamasi-sondajlara-baslayabiliriz-3393439 [Accessed: September 17, 2018]

[52] “ABD’lilerin kör bahaneleri var,” Vatan, September 9, 2018, http://www.gazetevatan.com/abd-lilerin-kor-bahaneleri-var-1198078-siyaset/ [Accessed: September 17, 2018]

[53] “PM Netanyahu meets with Cypriot President Anastasiades and Greek PM Tsipras,” Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs, http://mfa.gov.il/MFA/PressRoom/2018/Pages/PM-Netanyahu-meets-with-Cypriot-President-Anastasiades-and-Greek-PM-Tsipras-8-May-2018.aspx [Accessed: September 20, 2018]

[54] Itamar Eichner, “Classified Report: Egypt is Preferable to Turkey for Export of Natural Gas,” YNET, August 14, 2018, https://www.ynet.co.il/articles/0,7340,L-5328693,00.html [Accessed: October 17, 2018, Hebrew]

[55] Itamar Eichner, “Israel and Turkey conduct secret talks” YNET, September 17, 2018,

[56] “Minister vs. Erdoğan: ‘Unpredictable and Hasty, Turkey Is Becoming Undemocratic,” Channel 10, October 10, 2018, https://www.10.tv/news/173844 [Accessed: October 17, 2018, Hebrew]

תמונה: NASA [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

- בניית אתרים

- בניית אתרים