מדינות ערב מנרמלות את יחסיהן עם משטר אסד בניסיון לאזן את ההשפעות החזקות של איראן וטורקיה ולהשיג מידה מסוימת של השפעה על הארכיטקטורה המדינית-אסטרטגית החדשה של סוריה. מגמה זו מקבעת באזור מבנה אסטרטגי המעמיד את רוסיה במרכז. בטווח הארוך עלולה התפתחות זו להביא למתיחות ביחסים בין מדינות ערב השמרניות לישראל, במיוחד אם זו תפנה את מאבקה בנוכחות האיראנית בסוריה כלפי הצבא והממשל הסוריים, או תמשיך לתור אחרי הכרה דיפלומטית בסיפוח הגולן.

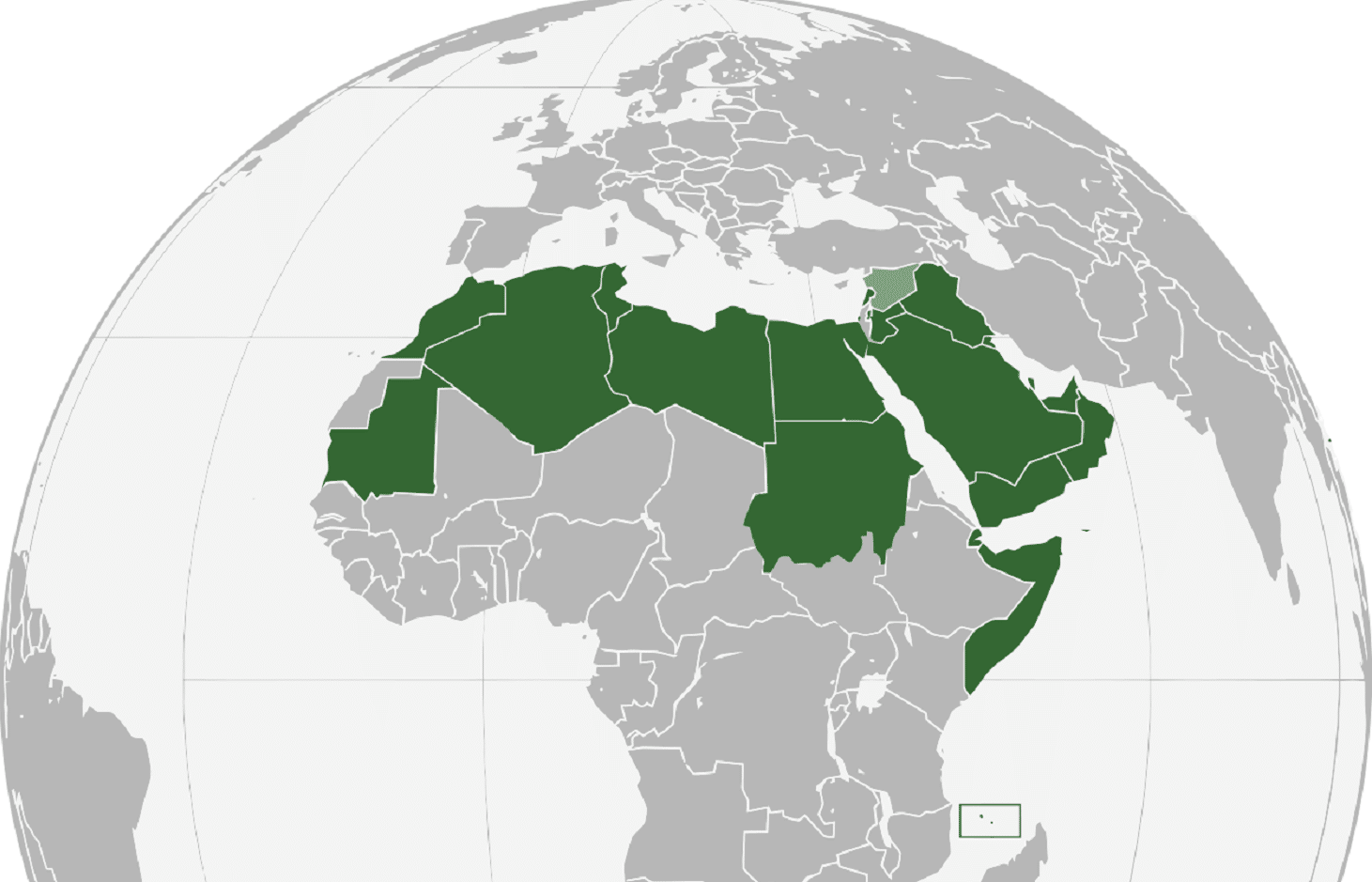

חזרתה של סוריה אל חיק העולם הערבי

מדינות ערב מנרמלות את יחסיהן עם משטר אסד בניסיון לאזן את ההשפעות החזקות של איראן וטורקיה ולהשיג מידה מסוימת של השפעה על הארכיטקטורה המדינית-אסטרטגית החדשה של סוריה. מגמה זו מקבעת באזור מבנה אסטרטגי המעמיד את רוסיה במרכז. בטווח הארוך עלולה התפתחות זו להביא למתיחות ביחסים בין מדינות ערב השמרניות לישראל, במיוחד אם זו תפנה את מאבקה בנוכחות האיראנית בסוריה כלפי הצבא והממשל הסוריים, או תמשיך לתור אחרי הכרה דיפלומטית בסיפוח הגולן.

יהושע קרסנה

מבוא

עם סיומה של מלחמת האזרחים בסוריה החלו מדינות ערב לנרמל את יחסיהן עם משטר אסד, זאת מתוך שאיפה לאזן את ההשפעות החזקות של איראן וטורקיה בסוריה, ובאותה הזדמנות להכחיד את השריד האחרון לאירועי האביב הערבי. אף שהמנהיגות הערבית השמרנית אינה מאמינה כי ביכולתה לחלץ את אסד מזרועות המחנה האיראני, היא מנסה להשיג מידה מסוימת של השפעה לפני שהמבנה המדיני-אסטרטגי החדש של סוריה יתקבע לבלי שוב. הדבר יסייע גם בחיזוק מבנה אסטרטגי חדש במזרח הערבי המעמיד את רוסיה במרכז.

לעת עתה, תהליך זה יכול להתקדם במקביל להידוק הקשרים בין מדינות ערב השמרניות לישראל, אך בטווח הארוך, אם התפייסותן של מדינות אלה עם דמשק תעמיק, היא עלולה לגרום למתיחות ביחסים בינן לבין ישראל, במיוחד אם תפנה ישראל את מאבקה בנוכחות האיראנית בסוריה כלפי מטרות צבאיות ושלטוניות או תמשיך לקדם מהלכים מדיניים להכרה בסיפוח רמת הגולן.

ההקשר הרחב

בשבועות שלאחר הכרזתו של הנשיא טראמפ על הסגת הכוחות האמריקניים התבהרה הדינמיקה האזורית סביב סוריה. מלחמת האזרחים בסוריה – שקדמה למערכה הבינלאומית נגד דאע”ש והתפתחה במקביל לה, ובדרך כלל בנפרד ממנה – הסתיימה עם חיסול ההתקוממות על ידי המשטר. להישג זה תרמו בעיקר “המתנדבים” השיעיים מחיזבאללה, עיראק ואפגניסטאן, מערכות הפו”ש והמודיעין I האיראניות והכוח האווירי הרוסי. הכוחות הבולטים המשפיעים על ההתפתחויות בתוך סוריה ובגבולותיה, וכפועל יוצא מעצבים היום את מדיניות המשטר הסורי, כוללים את רוסיה, איראן וטורקיה, ובמידה מסוימת גם את ישראל.

ב-2011, עם פרוץ המלחמה, תמכו מרבית מדינות ערב בנפילת משטר אסד, אך במהלך השנים התפצלו עמדותיהן כלפי דמשק בעיקר נוכח התגברות ההשפעה האיראנית בסוריה, לצד הצטמקותם ואז גוויעתם הסופית של הסיכויים לחילופי משטר בסוריה. מדינות אלה שבות היום אל סף דלתו של הדיקטטור הסורי. תהליך זה קיבל רוח גבית מספקותיהן של בעלות בריתה הערביות של ארצות הברית בנוגע לנכונותה להמשיך לגלות מעורבות משמעותית באזור, וכן מהצורך שלהן לנסות להשפיע על מאזן הכוחות האזורי ההולך וצומח מתוך התוהו.

התפייסות העולם הערבי עם סוריה

בידודה של סוריה בזירה הערבית בא לידי ביטוי בנובמבר 2011, עת הושעתה חברותה בליגה הערבית והקשרים הדיפלומטיים עימה נותקו על ידי רבות ממדינות ערב (אלג’יריה, עיראק, מאוריטניה, הרשות הפלסטינית ועומאן מעולם לא ניתקו את קשריהן עם סוריה). אלא שמשלהי 2018 החל לתפוס תאוצה תהליך של נורמליזציה ביחסים בין מדינות ערב לסוריה של אסד:

- הפגישה החמה והמתוקשרת בין שר החוץ הסורי, ווליד אל-מועלם, ועמיתו מבחריין, ח’אלד בן אחמד אל-ח’ליפה, בעצרת הכללית של האו”ם (30 בספטמבר 2018) הייתה הסנונית הראשונה לנורמליזציה של היחסים עם סוריה בקרב מנהיגות ערב.

- באוקטובר פתחה ירדן מחדש את מעבר הגבול עם סוריה, נסיב-ג’אבר, אחרי סגירה של שלוש שנים, ומינתה ממונה על היחסים בפועל (22 בינואר 2019) לשגרירות בדמשק. השגרירות אומנם הייתה פתוחה רשמית משנת 2011, אולם השגריר הוחזר לירדן, ומאז 2014 לא היה בסוריה ממונה מטעם הממשל הירדני. ייתכן מאוד שעמדתה של ירדן מושפעת גם מרצונה (בדומה ללבנון ולטורקיה) לראות את שיבתם של הפליטים הסורים, המהווים נטל חברתי וכלכלי כבד על הממלכה.

- ב-17 בדצמבר 2018 ביקר בסוריה נשיא סודן, עומר אל-בשיר (המבוקש על ידי בית הדין הפלילי הבינלאומי בגין פשעי מלחמה), ראש המדינה הראשון של חברה בליגה הערבית שביקר בסוריה מאז פרוץ מלחמת האזרחים.

- ראש המטה לביטחון לאומי בסוריה, הגנרל עלי ממלוק, יד ימינו של אסד, ביקר במצרים (23 בדצמבר 2018) ונפגש עם ראש המודיעין הכללי של מצרים, עבאס כאמל. ממלוק ערך ביקור פומבי במצרים גם ב-2016; יחסיה של מצרים עם סוריה השתפרו במידה ניכרת מאז הפיכת-הנגד שהעלתה את הנשיא א-סיסי לשלטון ב-2013.

- איחוד האמירויות הערביות (מאע”מ) פתחה מחדש את שגרירותה בדמשק ב-27 בדצמבר

- בחריין פתחה מחדש את שגרירותה בדצמבר

- מרבית הגושים הפוליטיים הדומיננטיים בתוניסיה הצביעו על נכונותם לחדש את היחסים הרשמיים עם סוריה שנגדעו ב-2011. שר החוץ התוניסאי, חמיס גהנאווי, קרא לליגה הערבית להשיב לסוריה את חברותה. צעד זה הינו משמעותי במיוחד הואיל והפסגה הבאה של הליגה הערבית תתקיים בתוניס במרץ (ראו להלן). ואם לא די בכך, ב-27 בדצמבר 2018 המריאה מדמשק הטיסה הישירה הראשונה של מטוס נוסעים סורי לתוניס בשבע השנים האחרונות.

- קבוצה של פקידי ממשל עיראקים, שכללה את היועץ לביטחון לאומי פאלח אל-פיאד, העומד בראש “יחידות הגיוס העממיות” (The Popular Mobilization Units – PMU) בעיראק, נפגשה עם אסד (29 בדצמבר 2018). עיראק מהדקת את יחסיה עם המשטר הסורי ואף דנה בהרחבת שיתוף הפעולה הצבאי והביטחוני עימו, כפיצוי על פינוי הכוחות האמריקניים מסוריה.1

מה עומד מאחורי מהלכים מדיניים אלה?

עמדתן של מדינות ערב נובעת מאילוצים מספר. הראשון הוא הצורך המשמעותי להתנגד ככל הניתן להשפעה האיראנית בסוריה של אחרי המלחמה, ולנסות לגמול את אסד, ולו באופן חלקי, מתלותו בטהראן. הבידוד הערבי של סוריה הוכח כבלתי מוצלח, ולמעשה חיזק את מעמדה של איראן בסוריה, ובעקבות כך את הגוש האיראני כולו. בעלי בריתה היחידים של סוריה באזור בשמונה השנים האחרונות היו איראן וחיזבאללה (אם כי, כאמור, העמדה המצרית תחת שלטון א-סיסי הייתה מאוזנת, כנראה עקב החצנת החשיבות שהמשטר המצרי רואה ביציבות ובלגיטימיות שלטונית). העיתון “אובזרוור” דיווח כי בשנת 2016 הציעה מאע”מ לנרמל את יחסיה עם דמשק כחלק מתוכנית כוללת להרחיק את אסד מאיראן, אך ממשל טראמפ דחה את התוכנית.

מדינות ערב השמרניות חוששות גם כי בהעדר תמיכה פוליטית וכלכלית למשטר הסורי עלולה אויבתן המושבעת האחרת, טורקיה – המחזיקה נוכחות צבאית ואזרחית משמעותית בצפון סוריה – לחזק את השפעתה בזירה הסורית. אף כי באופן תאורטי טורקיה יכולה להוות משקל-נגד להשפעה האיראנית בסוריה, מאע”מ וסעודיה, כמו גם מצרים, רואות בטורקיה כוח מפריע ומסוכן לא פחות מהרפובליקה האסלאמית. שר החוץ של מאע”מ צייץ בטוויטר כי “תפקידן של מדינות ערב בסוריה חיוני יותר כעת עקב הצורך להתמודד עם התפשטותן האזורית של איראן וטורקיה” (27 בדצמבר 2018). משרד החוץ של בחריין הסביר את החלטתה להשיב את היחסים על כנם בנימוק כמעט זהה: “לחזק את תפקידן של מדינות ערב על מנת לשמר את עצמאותה, ריבונותה ושלמותה הטריטוריאלית של סוריה ולמנוע את הסיכון להתערבות אזורית בענייניה”.

יתר על כן, מנקודת ראותן של מדינות ערב, החזרת המשילות בסוריה תביא להכחדת אחד השרידים האחרונים למהומות האביב הערבי של 2011–2012. זוהי התפתחות רצויה מאוד מבחינת המנהיגות השמרנית האנטי-מהפכנית של העולם הערבי. אף כי עדיין נותר לראות אם ההתפייסות תשרת את האג’נדה האנטי-איראנית של מחנה סעודיה-מאע”מ, אין ספק שהיא תקדם את סדר היום של “החזרת המצב לקדמותו”, המכוון נגד הכוחות הפוליטיים האיסלאמיסטיים, ובמיוחד האחים המוסלמים, הכוחות הדמוקרטיים/עממיים, קטאר וטורקיה.

ערב הסעודית עדיין לא נקטה עמדה רשמית בעניין ההתפייסות עם אסד, אך שתיקתה נוכח חידוש הקשרים של בעלות בריתה הקרובות במועצת שיתוף הפעולה של מדינות המפרץ (ה-GCC), כמו גם של סודן, שעימה פיתחה קשרים הדוקים בשנים האחרונות במיוחד בכל הנוגע למלחמה בתימן (שם מנוהל חלק ניכר מהלוחמה הקרקעית על ידי חיילים סודנים), מעידה על הסכמתה למהלכים אלה. כמו בסוגיות אחרות, גם כאן הולכת קטאר, שהייתה המתנגדת החריפה ביותר למשטר אסד מתחילת מלחמת האזרחים ועד עצם היום הזה, נגד הזרם, ודוחה את רעיון ההתפייסות הערבית עם סוריה. כך או כך, דוחא מרגישה בנוח גם עם רמה גבוהה הרבה יותר של השפעה טורקית ואיראנית בסוריה מזו המקובלת על ריאד או אבו דאבי, לכן יש לה פחות מה להפסיד מעמידה על עקרונותיה.

מן הצד הסורי, אסד מתעניין הן בלגיטימציה שיקנה לו חידוש הקשרים עם מדינות ערב, והן בסיוען הכספי לשיקום הכלכלה והתשתיות במדינה, שעלותו מוערכת בסכום של בין 300 ל-400 מיליארד דולר. הן איראן, למרות להיטותה לשלב חברות איראניות במאמצי השיקום ולממש את השקעתה במשטר אסד, והן רוסיה, אינן יכולות להעניק לסוריה סיוע בהיקף כזה. לאור כך שמשטר אסד אינו צפוי לקבל סיוע רב ממדינות המערב, הכסף שיוזרם ממדינות ערב העשירות הוא עניין של הכרח. אחד האתגרים שיעמדו בפני מדינות המפרץ יהיה כיצד לתרום לשיקום סוריה מבלי להתנגש עם הסנקציות האמריקניות והרב-צדדיות המוטלות על גופים ואישי מפתח בסוריה.

חזרה לליגה הערבית? משוכה סמלית

המהלכים לחידוש ההידברות עם סוריה, אך גם הוויכוחים בסוגיה זו, באים לידי ביטוי בצעדים ל”הפשרת” חברותה ה”מוקפאת” בליגה הערבית. לצעד כזה יש אומנם משמעות מעשית זניחה מאוד אך משמעות סמלית גדולה, שכן אותו משטר עצמו, זה שנודה וגורש על ידי עמיתיו הערביים, יחזור שוב לשורה מבלי שעשה כל תיקון בהתנהלותו. באפריל 2018 אמר מזכ”ל הליגה הערבית, אחמד אבו אל-ע’יית’, כי ההחלטה להשעות את סוריה הייתה “חפוזה”, אמירה שעוררה בעקבותיה ציפיות שסוריה תשתתף בפסגה הכלכלית הערבית שהתקיימה בביירות (ב-19–20 בינואר), אולם בסופו של דבר היא לא הוזמנה לאירוע. אבן הדרך הבאה תהיה פסגת הליגה הערבית שתתקיים ב-31 במארס בטוניסיה, שם צפויה חברותה של סוריה להיות הנושא המרכזי שיידון. יחד עם זאת, הליגה הערבית מקבלת את החלטותיה בקונצנזוס, ועדיין קיימת התנגדות להחזרת סוריה בין 21 המדינות החברות בליגה, בעיקר, כאמור, מצד קטאר. אבו אל-ע’יית’ ציין (11 בפברואר 2019) כי “אני עדיין לא רואה מסקנות המובילות לקונצנזוס שאנו מדברים עליו… השאלה היא לא מתי, השאלה היא האם”.

נראה שחלק מהמדינות עושות הבחנה בין הידוק הקשרים הדו-צדדיים, המבוססים על אינטרסים ועל שיקולים אסטרטגיים, לבין הצעד הסמלי הבא לידי ביטוי בהחזרתה הרשמית של סוריה אל חיק העולם הערבי, מבלי שהביעה כל חרטה. הדיווחים האחרונים בעיתונות הערבית רואים הקשחה בעמדה המצרית בסוגיה זו, בעיקר בזכות מאמציהן של ארה”ב וצרפת. הם מצטטים את שר החוץ המצרי, סאמח שוקרי, האומר כי מצרים לא תתמוך בהצעה להחזיר את סוריה לליגה הערבית בפסגה שתתקיים במרץ. לאחרונה גם הצהיר כי סוריה אינה יכולה לחזור לחברות פעילה בליגה בלי לנקוט צעדים בהתאם להחלטת מועצת הביטחון של האו”ם 2254. החלטה זו קוראת, בין השאר, לתהליך בחסות האו”ם שיכלול הקמת “ממשל אמין, כולל ועל-עדתי” תוך שישה חודשים, קביעת לוח זמנים ותהליך לגיבוש חוקה חדשה, ו”בחירות חופשיות והוגנות” על פי החוקה החדשה, שתתקיימנה תוך 18 חודשים, תנוהלנה תחת פיקוח של האו”ם ותכלולנה את כל האזרחים – לרבות סורים גולים – הזכאים להשתתף בהן. על פי הדיווחים, גם ערב הסעודית מתנה את החזרתה של סוריה ביישום ההחלטה.

אין זה סביר שסוריה תסכים לתנאים אלה, שאף אינם זוכים לתמיכתן התקיפה של בנות שיחה המרכזיות: רוסיה, איראן וטורקיה. סגן שר החוץ הסורי, פייסל אל-מקדאד, אמר כי מדינתו תחזור לבסוף לליגה הערבית, אך הדגיש כי הממשלה בדמשק לעולם לא תיכנע לסחיטה או תיענה לתנאים להשבת חברותה.

רוסיה מעודדת מאוד את השתלבותה מחדש של סוריה בעולם הערבי, ובמיוחד את קבלתה מחדש לליגה הערבית. התפתחות כזו תשריין את ניצחונה של מוסקבה בסוריה, ואולי גם תשקף את רצונה לדלל את ההשפעה האיראנית בדמשק. ראוי לציין כי בשנים האחרונות פיתחה רוסיה קשרים משמעותיים עם כמה מהשחקניות הערביות הגדולות, הפרו-אמריקניות לכאורה, דבר שעשוי להסביר גם את השינוי בעמדותיהן ביחס לדמשק. בכל מקרה, השידולים הרוסיים נכנסו להילוך גבוה. שר החוץ, סרגיי לברוב, ביקר בסוף ינואר בתוניסיה, מרוקו ואלג’יריה, וקרא למארחיו להחזיר את סוריה ל”משפחה הערבית” לפני הפסגה במרץ. מיכאיל בוגדנוב, שליחו המיוחד של הנשיא פוטין למזרח התיכון וצפון אפריקה, ביקר בקהיר לפגישה עם שר החוץ שוקרי ועם מזכ”ל הליגה הערבית, אבו אל-ע’יית’, ומזכיר מועצת הביטחון הרוסית, ניקולאי פטרושב, ביקר במצרים ובמאע”מ.

ארצות הברית, מצידה, חותרת לרסן את ההתפייסות הערבית עם דמשק – גם במהלך ביקורו של שר החוץ, מייק פומפאו, במזרח התיכון בחודש שעבר ובשולי הכנס האחרון בוורשה – וליצור זיקה בינה לבין השינויים המשמעותיים בהתנהלות הסורית, ובמיוחד בכל הנוגע לקשריה עם טהראן.

מסקנות

אין זה סביר שחידוש קשריו של אסד עם מדינות ערב ישפיע באופן מהותי על קשריו הביטחוניים עם איראן בטווח הקרוב. ראשית, משום שקשריו האסטרטגיים עם איראן קדמו למלחמת האזרחים, ואכן הוכיחו את עצמם. שנית, משום שאיראן (כמו גם חיזבאללה והמיליציות השיעיות) נטועה באופן עמוק כל-כך במערכת הביטחון הסורית, שקשה לראות כיצד ניתן לעקור אותה ממנה.

אף כי ספק אם המנהיגים הערבים השמרנים מאמינים כי יש ביכולתם לחלץ את אסד מזרועות המחנה האיראני (הוא נמצא בקשרים עם איראן מאז ימי המהפכה, לפני ארבעים שנה), נראה כי אינם מוכנים לקבל את העליונות האיראנית באופן פסיבי, וכי הם מנסים להשיג מידה מסוימת של השפעה לפני שהמבנה המדיני-אסטרטגי החדש של סוריה שלאחר המלחמה יתקבע לבלי שוב.

לחיזוק המגעים עם העולם הערבי הרחב, ולמעורבות כלכלית ערבית משמעותית בתוכניות השיקום של סוריה, עשויה להיות השפעה ממתנת על ההתנהלות הסורית במהלך הזמן, והם עשויים להביא לצמצום תלותו של אסד באיראנים בטווח הארוך יותר. הם גם אולי “יקשיחו את גבה של סוריה” אל מול החדירות והשאיפות הטריטוריאליות של טורקיה, ויבלמו את מעורבותה המשמעותית של אנקרה בשיקום הכלכלה הסורית, וכפועל יוצא, את חיזוק השפעתה.

בכל מקרה, שיפור היחסים בין המדינות הערביות השמרניות למשטר הבלתי משוקם של אסד יסייע בחיזוק ובקיבוע ארכיטקטורה אסטרטגית חדשה במזרח הערבי המעמידה את רוסיה במרכז.

אחת השאלות המעניינות היא איזו השפעה תהיה להתפייסות זו על הידוק קשריהן של מדינות אלה עם ישראל. לעת עתה, נראה כי שני התהליכים יכולים להתקדם במקביל. אף כי ייתכן שהיחסים הרשמיים עם סוריה ישוקמו, קשריה עם רבות ממדינות ערב עדיין רחוקים מלהיות חמים, ובטווח הקצר עד בינוני כנראה לא יגברו על היתרונות האסטרטגיים הנובעים מקשריהן הבלתי פורמליים עם ישראל.2

בטווח הארוך יותר, אם התפייסותן של מדינות ערב השמרניות עם דמשק תעמיק, היא עלולה לגרום למתיחות ביחסיהן עם ישראל, במיוחד אם תפנה ישראל את מאבקה בנוכחות האיראנית בסוריה כלפי מטרות צבאיות ושלטוניות סוריות או תמשיך לקדם מהלכים מדיניים להכרה בסיפוח רמת הגולן.

[1] יחסיה של עיראק עם הממשל האמריקני מלווים במתחים, כפי שעולה מהצהרתו של הנשיא טראמפ כי ישאיר את הכוחות האמריקניים בעיראק כדי לפקח על איראן, הצהרה שזכתה להכחשות ולגינויים מצד עיראק. ראוי לציין שבמסגרת מסיבת עיתונאים שערך שר החוץ העיראקי, מוחמד עלי אל-חכים, עם עמיתו הרוסי במהלך ביקורו האחרון במוסקבה (29–30 בינואר 2019), כינה את היחסים בין המדינות “שותפות אסטרטגית”.

[2] ראוי לציין שגם מצרים (מאז 2005) וגם ירדן שומרות על יחסים דיפלומטיים הן עם ישראל והן עם סוריה שלפני האביב הערבי.

סדרת הפרסומים “ניירות עמדה” מטעם המכון מתפרסמת הודות לנדיבותה של משפחת גרג רוסהנדלר.

תמונה: Danalm000 [CC BY-SA 3.0], from Wikimedia Commons

- בניית אתרים

- בניית אתרים