The Iranian “corridor” is a central project for the mullahs in Iraq and Syria, involving a highway which would connect Tehran with Damascus.

Iran has been busy building a land route that runs from its territory to Syria and the Mediterranean through Iraq. This was made possible under the cover of the struggle against ISIS, which enabled the Iranian regime to represent its participation in the fighting in Syria as legitimate and as an international duty.

The aim of the route, which is a fully controlled Iranian territory for all intents and purposes, is to secure Iranian access to Hezbollah regardless of the combat situation in Syria, as well as to enable the IRGC to enhance their efforts to establish a permanent presence on Syrian soil. These efforts are already evident in the Syrian Golan heights, which serve as a key position in the context of Iran’s ambition to create an intelligence capacity and an offensive military infrastructure vis-à-vis Israel and a subversive potential towards Jordan.

In December 2017 the Iranian route project was given a significant boost when the Syrian army and pro-Iranian forces, including Lebanese Hezbollah and the Iraqi Shi’a militias al-Nujaba’ and Kata’ib Hezbollah, wrested control of the border pass connecting Iraq and Syria (al-Qa’im on the Iraqi side, Abu-Kamal on the Syrian) from ISIS, and began to use it as a conduit for arms transfers.

In the context of the determined Israeli effort to frustrate the project of establishing Iranian forces in Syria, various strikes have been launched against targets associated with IRGC Quds Force, Shi’a militias and Hezbollah. In this context, it is reported that in June 2018 a facility used by the Kata’ib Hezbollah militia was struck near Abu-Kamal on the Syrian-iraqi border.

To avoid Israel’s air strikes, the Iranians has put in motion an airlift to Damascus, Aleppo and Beirut, through which they continue to provide missile technology and other arms and munitions. They enjoy the cooperation of the Lebanese Army, which is also in charge of the Beirut airport. Still, Iran continues to work intensively on establishing the ground route, which can be used more extensively than an airlift – which can only carry limited amounts and types of military equipment.

Planning for the full project was pushed forward further in a meeting between the Chiefs of Staff of Iran, Iraq and Syria in mid-march 2019 in Syria. At the meeting, the three announced the opening of a ground passage between Iraq and Syria. Iraqi sources divulged to the media that of the three passage points between Iraq and Syria, it will be al-Qa’im that would be used for this purpose.

The London-based Qatari daily al-Arabi al-Jadid reported on March 26 an exclusive story according to which Iran is now putting forward plans for the construction of a highway that would connect Tehran with Damascus via Iraq, with a future extension into Lebanon. Iraqi sources told the daily that the road construction was anchored in an agreement recently signed between Iran and Iraq. An Iranian technical mission recently visited Iraq and met with senior government officials. The planned project apparently came up during president Rouhani’s visit in Iraq in mid-March 2019, in which he also called upon the Iraqi government to realize the building of a rail link from Shalamcheh on the Iran-Iraq border to Basra and from there to the Syrian coast at Latakia, a project which Iran has been promoting since 2013.

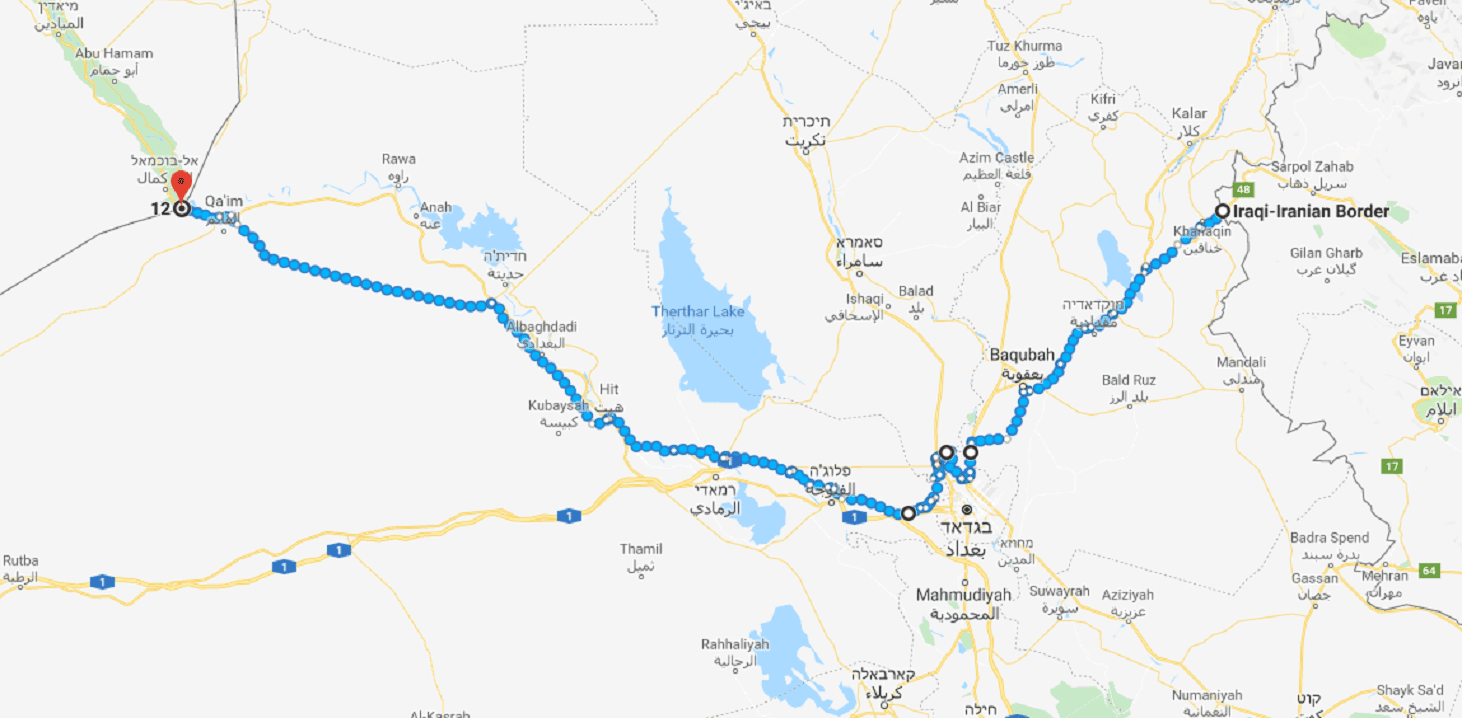

Currently, the Iranians are discussing with the Iraqi side the route of the highway and other technical aspects related to the project. They have suggested to the Iraqis two optional routes, both originating from Kermanshah Province on the Iran-Iraq border.

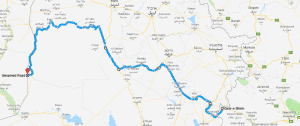

First putative route – Qasr-e Shirin to Deir al-Zor

This route would begin from the town of Qasr-e Shirin in Kermanshah Province, from there to Kalar in Iraq, further to TuzKhurmatu, from there to the Hamrin mountain range, to Ninewa and ultimately to Deir al-Zor governorate in Syria.

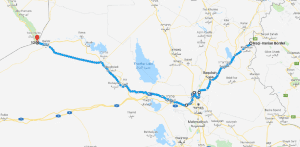

Second putative route – Kermanshah to al-Qa’im

This is the route that served as the official conduit between Iraq and Syria until the civil war in Syria erupted in 2011. It enters Iraq through Diyala province on the Iran-Iraq border, on to the north of Baghdad, Abu Ghraib, Faluja and Ramadi, and enters Syria via al-Qa’im.

According to the report, Iran’s main concern is to keep the route as far away as possible from American bases and U.S. military presence, as well as away from all other participants in the anti-ISIS coalition. Moreover, Iran – currently under a sanctions regime which is already being feltin various budgetary aspects – would prefer to use the existing road infrastructure to reduce costs.

According to the Iraqi sources, the Iranians, now more eager than the Iraqis to push forward with the plan than the Iraqi side, are presenting the Iraqi government with economic incentives that would accrue from the project. These would include work opportunities for Iraqis, the use of private sector Iraqi trucks, and an option for the Iraqi authorities to collect fees from cars goings to Syria.

Apparently, the leak to al-Arabi al-Jadid about the highway plans came from sources in Iraq opposed to the project. They told the daily that the project was clearly meant not to serve commercial needs of both countries but to be used by the IRGC and the Shi’ite militias supported by the Quds Force. Thus, Muhammad Nuri Abed-Rabbo, a senior member of the al-Nasr faction led by former Iraqi Prime Minister Hayder al-Abadi, expressed in an interview to the daily firm opposition to the project, which he described as being dangerous for Iraq’s security and economic interests. He therefore called for a thorough discussion of the implications of the project, putting Iraq’s interests above those of Iran. He described it as designed to advance Iranian control over part of Iraq’s territory, and defined it as part of Iran’s “Shi’a Crescent” vision.

The U.S. Administration is apparently aware of the emerging danger from Iran and the Shi’ite militias at its service, and therefore chose to include in the list of sanctions, in early March 2019, the Iraqi Shi’ite militia of al-Nujaba’, backed by the Quds Force. While it did take part in the fighting against ISIS in Iraq, the main activities of this militia have been carried out in Syria, where it played a major part in pro-Iranian military activities. In January 2019, there were reports that President Trump intends to demand that Iraq should disband the 67 Shi’ite militias which constitute the “Popular Mobilization Forces” (al-Hashd al-Sha’abi), an initiative which led to threats by Iraqi Shiite militias against American forces in Iraq. Given this vulnerability in Iraq, the U.S. cannot actively pursue this demand. The Administration seems focused upon the economic dimension of its efforts against Iran and its proxies, and does not wish to embark on a course of action that could lead to a direct military confrontation with Tehran.

Promoting the Tehran-Damascus highway project may enhance the Iranian presence in Iraq and Syria, and directly contradicts U.S. interests in the region. The Administration, and Congress, should therefore look at measures designed to foil the project, by applying heavy pressure on Iraq’s government headed by Prime Minister Adel Abd al-Mahdi. Frustrating the project would serve U.S. policy in Iraq, which seeks to bolster Iraqi sovereignty, as Secretary of State Pompeo made clear in his phone conversation with Abd al-Mahdi in early March.

JISS Policy Papers are published through the generosity of the Greg Rosshandler Family.

photo: Google Maps

- בניית אתרים

- בניית אתרים