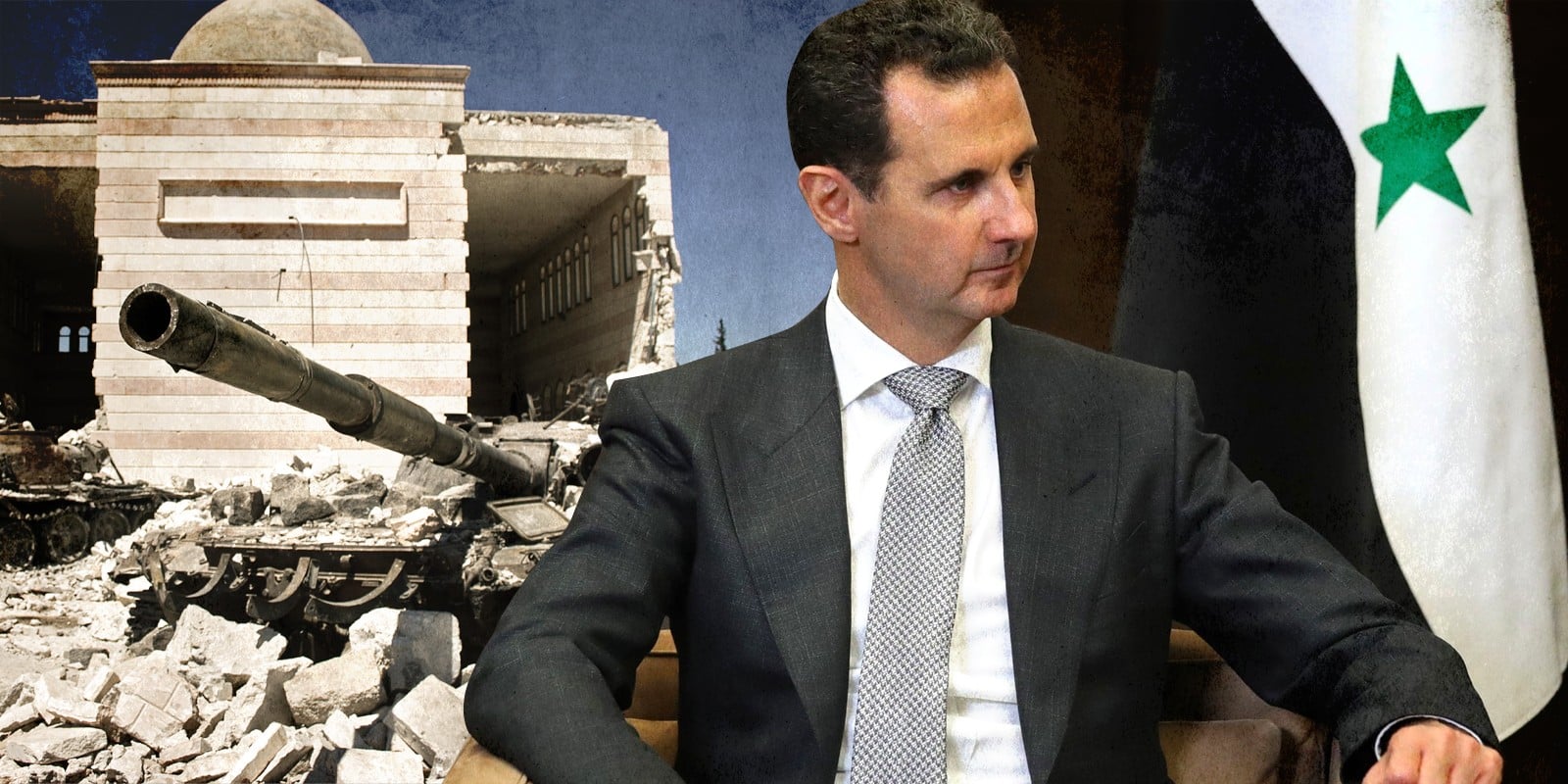

Bashar Assad is not about to fall, But economic deterioration, regime infighting, sanctions and unrest are combining to place his regime under renewed, severe pressure

No major combat operations are currently under way in Syria. But while the civil war which began in 2011 may be effectively over, events in the country indicate that no clear winner has emerged from the conflict. Syria appears set to remain divided, impoverished and dominated by competing external powers.

The Assad regime, meanwhile, is beset by infighting at top levels, even as significant unrest returns to regime-controlled areas.

In late 2018, the regime appeared on the verge of strategic victory in the war. The rebels had lost their final holdings in the south of the country. US President Donald Trump had announced an imminent withdrawal from northeast Syria. The remaining rebels in the northwest were isolated, and dominated by extreme Sunni jihadi elements.

But the sense that one final round of diplomatic and military action could restore pre-2011 Syria has receded to the far distance. The Americans, despite periodic presidential tweets, are still there. The rebels, meanwhile, have benefited from deepening Turkish patronage and the desire of the Russians to draw Turkey closer. As a result, Syria remains territorially divided, with the regime controlling just over 60% of the country.

But even in the areas under his control, Assad is not succeeding in returning stability and reconsolidating his rule. The problem, first of all, is economic. Syria is a smoking ruin. Neither Assad nor his patrons in Moscow and Tehran have the money to begin desperately needed reconstruction. The Europeans and the US, meanwhile, will not offer assistance, as long as the regime refuses all prospects of political transition.

This stalemate is not endlessly sustainable. Lack of money makes rebuilding impossible. This, in turn, leads to renewed instability.

The economic fortunes of the Assads have deteriorated significantly further in recent weeks. The Syrian pound is in free fall. The official exchange rate is now 700 Syrian pounds to the dollar. The current black market rate is 2,300 Syrian pounds to the dollar. Prior to 2011, the rate stood at 50 to one.

Around 80% of Syrians are living below the poverty line. Long daily queues for subsidized bread are a familiar site in Damascus. Now, as a result of the devaluation of the currency, even basic foodstuffs stand beyond the reach of many Syrian families. Inflation is currently at 20%.

Ahmad al-Rashid, a Syrian refugee now resident in the UK, described the situation in the following terms in a Facebook post after conversations with friends remaining in Syria: “People can’t afford to buy basics now. I spoke to some people in the country and they are losing their minds. Money doesn’t have any value anymore! Bakeries are closing, doctors are closing, shops are closing, businesses are closing. Millions of parents aren’t able to put food on the table for their kids. They can’t buy food or milk for their babies. Some people are offering to sell their organs so they can help their families.”

This depiction is not limited to individuals associated with the opposition. Danny Makki, a journalist with close connections in Syrian government circles, tweeted on June 7 that “the economic situation in Syria is at breaking point, medicine is very scarce, hunger is becoming a normality. Poverty is at the worst point ever, people even selling their organs to survive.”

A number of factors are causing the current predicament, in addition to sanctions and the isolation and stagnation of regime-controlled Syria.

COVID-19 and the resultant three-month lockdown have devastated the already weakened private business sector.

The travails of neighboring Lebanon have also impacted on Syria. Many Syrians placed their savings in US dollars in Lebanese banks. The current crisis in Lebanon has led to restrictions on withdrawal of dollars. This, in turn, has led to a dollar shortage in Syria and further devaluation of the local currency.

This already critical situation is about to get worse. In mid-June, the US Caesar Act will take effect. Named after a Syrian military police photographer who in 2014 first provided evidence of mass killings in regime jails, the sanctions contained in this act are set to severely penalize anyone doing business with Assad’s Syria.

The Caesar Act was passed into law in the US in December 2019 as part of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2020. It focuses on the infrastructure, petroleum and military maintenance sectors, and contains provisions for penalties against third parties doing business with Syria. This is set to deter third-party countries, such as China and the United Arab Emirates, that have shown interest in investment in reconstruction in Syria.

AGAINST THE background of economic meltdown, grassroots-level unrest has reappeared in regime-controlled areas. In Deraa province, in the southwest of the country, a renewed low-level insurgency is under way.

According to the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, 489 attacks have taken place on regime forces in the province since last June. The observatory puts the death toll in these attacks at 322.

The largest-scale single act of violence in recent months took place on May 4, when former rebel commander Qasem al-Subehi led an attack of 15 former rebels on a police station outside the town of Muzayrib in western Deraa in which nine regime policemen were killed.

The Syrian Army’s 4th Division is currently building up forces in the western Deraa area.

In Sweida province, which has a 90% Druze population, stormy demonstrations have taken place over the past week. This is of particular significance because Sweida has throughout the war maintained an uneasy coexistence with the regime. The demonstrations are small, involving about 300 young men and women. That they are happening at all will nevertheless be worrying for defenders of the regime.

The latter will presumably also have noted that the demonstrators in Sweida have revived many of the slogans of the first days of the uprising. These include “Syria belongs to us – not to the house of Assad,” “A free Syria – out with Iran and Russia,” and “The people demand the fall of the regime.”

Elsewhere in Syria, in a notable sign of the times, the “Syrian Interim Government” (a Turkish-backed administrative body in the Turkish-controlled northwest) announced this week that the Syrian pound would be replaced by the Turkish lira in its area of control.

This decision appears to have followed a notable trend in recent months in which sellers and merchants sought to price goods in the more stable Turkish currency. The Turkish Postal Directorate, which maintains facilities in Turkish-controlled parts of northwest Syria, has now begun to circulate large quantities of Turkish currency in the area.

Lastly, of course, evidence has recently emerged of tensions at the highest levels in the regime. Assad recently turned on a former key ally at the very heart of his regime, his cousin Rami Makhlouf, in a move rumored to relate to clashing ambitions between Makhlouf and Asma Assad, the president’s wife.

Bashar Assad is not about to fall. But severe economic deterioration, regime infighting, reignited unrest from below and fresh sanctions about to bite are combining to place his regime under renewed, severe pressure.

It is all a long way from the victory parades of just two years ago.

Published in The Jerusalem Post 12.06.2020

JISS Policy Papers are published through the generosity of the Greg Rosshandler Family.

Photo: Kremlin.ru / Cees Joppe

- בניית אתרים

- בניית אתרים