Chinese investment in Iran would help Tehran withstand US economic pressures, and exacerbate the Western crisis with Iran

A strategic agreement between the People’s Republic of China and the Iranian regime raises dangerous prospects. This may involve the investment of huge sums of money in Iran’s oil and gas infrastructure. Such a deal might enable Tehran to withstand US pressures. Meanwhile, Iran is escalating the use of violence, including a major attack on Saudi oil facilities, and has resumed its march towards a nuclear bomb. Ultimately, Israel and the relevant Arab nations should work together to warn Beijing, discreetly, that this path may lead to a further escalation, and perhaps to a highly destabilizing war that will be damaging to China’s own interests.

****

While American (and Israeli) political attentions have been focused elsewhere, the crisis with Iran is approaching a dangerous boiling point. The US has been joined by key European nations in firmly asserting Iran’s direct role in the attack on major Saudi oil facilities. Four out of the six JCPOA participants have now cast the blame on Tehran for this dramatic escalation of violence. The IAEA has confirmed that Iran is in violation of JCPOA restrictions and is now installing new centrifuges that would accelerate the march towards the bomb. Given the clear preference of the US to avoid military action and instead tighten the sanctions further, the position of the People’s Republic of China may turn out to be of utmost importance.

During Iranian Foreign Minister Zarif’s recent visit in Beijing, he apparently negotiated a “road map” for the implementation of a “Comprehensive Strategic Partnership” between the two countries. This is a term the PRC uses to describe the highest level of cooperation (grade 5) with a friendly country. (Israel is at grade 3). The plan will possibly include, according to some unverified reports, a huge long-term deal, keeping the Chinese market open to Iranian oil – despite the sanctions – and Iran open to very large-scale Chinese investment, with a general scope of hundreds of billions of dollars. (Arms sales were not mentioned, but if indeed the two countries do forge an anti-American alliance, this cannot be ruled out).

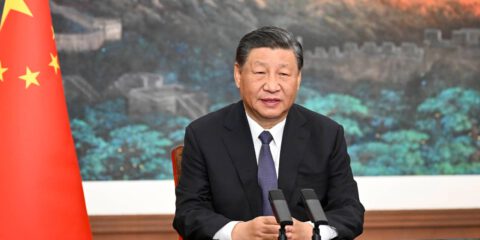

Even if Israel does maintain close relations at the personal level with Xi Jinping and the Chinese leadership, it will not be easy to dissuade Beijing from taking actions that serve Iran’s interest and contradict that of the United States. Recent interactions with Chinese think tanks made it very clear that anger and wounded pride about the actions taken against China by the Trump Administration are running high. While the official line still speaks of “commercial competition,” the unofficial but prevalent view in Beijing is that the threshold has been crossed over into a trade “war,” with all that this implies.

If so, the Chinese urge to add to Trump’s worries – and give China some powerful cards to play with – may prove to be difficult to resist. Unlike Turkey, which has come to be seen by Beijing as playing a subversive role in Xinjiang (the largely Uighur areas of western China, where the restive Sunni Muslim population speaks a Turkic language), Iran has not taken any actions which China might see as directly harmful to its interests. While it would be misguided to speak of an alliance (Chinese policy deliberately avoids both the word and the concept, and prefers to speak of levels of partnership), it may well be proper to view the Iranian-Chinese relationship in terms of a commonality of (anti-American) purpose.

If so, what can still be done to avert an outcome which might severely undermine the US “maximum pressure” strategy (which Israel has wholeheartedly endorsed)? A possible answer may be provided by looking back at what worked in 2010, when Israel apparently played a significant role in persuading China to vote for sanctions against Iran. (Strange as this sounds in retrospect, Israel worked in close coordination with President Obama and Secretary of State Clinton on this). The initial working assumption was that the Chinese (who rarely used their veto power) could at best be persuaded to abstain at the United Nations Security Council, thus making a sanctions resolution possible. But on the day, June 9, 2010, the PRC voted in favor of a severe sanctions resolution, UNSCR 1929. (The only “no” votes – 13 to 2 – were those of Turkey and Brazil, who saw themselves as playing a triangulating role between the west and its enemies).

What persuaded China to go along? Then, as now, it was the firm official position of the PRC that Iran should not be allowed to violate the NPT and achieve a military nuclear capability. At least in theory, it is still the view in Beijing that after North Korea, another crack in the NPT dam could bring the entire structure down, with severe consequences for global security. Still, Beijing has been able all too often to persuade itself to ignore the obvious facts and assert that Iranian activities are legitimate in nature. (Most recently, they officially rejected the evidence that Iran was behind the disruption of shipping in the Straits of Hormuz).

What forced them to re-think their stance in 2010, and even denounce Iran as a country which “makes paper balls from international resolutions,” was the prospect, aggressively presented by high level Israeli officials that without maximal pressure war might become the only option for preventing Iran from getting the bomb.

Such a war, now even more that in 2010, could have disastrous consequences for China’s basic, almost existential, interests. The latest attack on the Saudi oil facilities proves the point. It serves as a reminder that it is not President Rouhani and Foreign Minister Zarif, but the Supreme Leader and the IRGC which determine policy in Iran. To coddle Iran at this point is to invite further subversion further violence, and a likely dash towards the bomb, with consequences that could unsettle the world economy. This would dash the prospects of continued Chinese growth and the achievement of President Xi’s goals for the coming decades.

Given the signs of hesitation and discord in Washington, particularly after John Bolton’s departure, it may be difficult to persuade the leadership of China that a warlike American response to Iran’s present course of action is indeed inevitable, or even possible. With the media still speculating about a possible “summit” between the presidents of Iran and the US (– note that this is a false term, since Rouhani is not Iran’s leader), Beijing may well conclude that Trump is looking for an easy way out.

It is at this decisive moment, once a new Israeli government is formed, that Israel can help post an unambiguous message on China’s virtual wall. The choice is not between “maximum pressure” and business as usual. It is between maximum pressure and a possible negotiation with Iran from a position of strength, or further escalation, growing tension, and perhaps even a preventive war, with all that the latter may entail.

This message need not, indeed should not, be public. Open pressure on a power like China can often be counterproductive. But in discreet dialogue at the highest professional levels – national security staff, intelligence community, foreign ministry, and military-to-military – the message should be clear and consistent. It should be closely coordinated with what the Chinese will hear not only from the US but also from key Arab countries. All this can be effectively backed by dialogue at the level of think tanks. Those on the Chinese side should be viewed as direct conduits to their government. Experience indicates that if such an effort is well-orchestrated, it can have an impact.

JISS Policy Papers are published through the generosity of the Greg Rosshandler Family.

photo: Official website of Ali Khamenei, Supreme leader of Iran [CC BY 4.0 ]

- בניית אתרים

- בניית אתרים