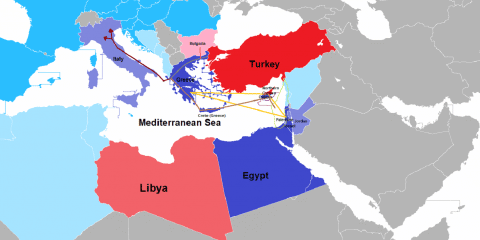

Everything short of a military confrontation needs to be done, though, to deter Erdogan from establishing a barrier diagonally across the Mediterranean, barring Cyprus, Egypt and Israel from connecting their gas infrastructure to Greece and hence to Europe.

A ceasefire agreement in Libya, coupled with an arms embargo, was reached at the summit in Berlin on January 19, 2019. It remains to be seen whether it can hold. Turkey and Russia played a major role in this outcome, though it does not signal Russian support for Erdogan’s plans in the eastern Mediterranean. Specifically, Russia did not endorse Erdogan’s MOU with the “Government of National Accord” in Tripoli (Nov. 27) over the extension of Turkey’s EEZ borders across the Mediterranean.

In any case, Khalifa Haftar presence in Berlin indicated that the “Libyan National Army” can no longer be ignored by the government in Tripoli and its Turkish ally. Haftar has previously promised, during his visit in Athens, to annul the MOU. Israel’s role – in close coordination with Greece, Cyprus and Egypt – must be to help line up US support; encourage Europe to continue to reject the Turkish EEZ claims; and ensure that the Russian position does not embolden Turkish ambitions. Short of military confrontation, all measures should be taken to deter Erdogan, and to confirm that the MOU must be repudiated.

Much has happened in the eastern Mediterranean in the first few weeks of 2020. The 7th tripartite Greek-Cypriot-Israeli summit (the first one attended by the new center-Right prime minister of Greece, Kyriakos Mitsotakis – the previous six were with his left-wing predecessor, Alexis Tsipras) was held in Athens on January 2. At the very same time, a parliamentary vote in Ankara authorized a military intervention in Libya. Putin’s came for talks with Erdogan in Istanbul (followed by his imperial visit in Syria). A tentative ceasefire was brokered between the forces loyal to “Government of National Accord” (GNA) in Tripoli, and the “Libyan National Army” led by Field Marshal Khalifa Haftar. It soon came to the verge of collapse, however, amidst Turkish recriminations and the failure to outline any further progress towards reconciliation.

On January 15, the eastern Mediterranean Gas partners – Italy, Greece, Cyprus, Egypt, Israel, Jordan and the Palestinian Authority – met in Cairo, as scheduled – but at this time, signaling defiance of Turkey’s attempts to drive a wedge between the seven. They decided that the EMGF would from now on be defined as a regional organization. France now seeks to join the forum, and the US expressed an interest in serving as a permanent observer.

This was also the occasion for a formal announcement by the two Energy Ministers that Israeli gas has begun to flow to Egypt, a landmark event in the history of regional cooperation (Israel has been supplying gas to Jordan for some time, but on a smaller scale). Meanwhile, intense Egyptian diplomacy was aimed at shoring up support against the GNA (which Cairo deems to be controlled by the Muslim Brotherhood and associated terrorists). This was followed by the Egyptian Foreign Minister’s mission to Libya’s western neighbors, Algeria and Tunisia, to deepen the GNA’s isolation.

Amidst all this, the conflict in Libya, and the renewed bid by the self-declared Libyan National Army (LNA), led by Haftar, to take Tripoli or at least lay siege to it, stand at the core of this struggle for dominance in the eastern Mediterranean. Haftar is backed by Egypt (and her Gulf backers, primarily UAE), Russia, and France, despite the GNA’s formal status as the “internationally recognized” government in Libya. The LNA enjoys military superiority in the field, despite the continued allegiance to the GNA of the formidable militia of the city of Misrata, one of the most effective fighting forces amidst the Libyan chaos. Hence the sense of urgency in Ankara and the decision to deploy troops. (Some advisers and technicians, as well as pro-Turkish Sunni Syrian Islamist militiamen, have been there already since mid-2109; but their number may grow, and their presence is now overt). Erdogan is determined to “teach Haftar a lesson.”

Clearly, the stronger Haftar grows, let alone if Tripoli falls, the less able Turkey would be to assert the validity of its EEZ map (which is drawn, in a manner which ignores the position of the Island of Crete as a sovereign Greek territory). In a significant visit in Athens, on January 17, Haftar openly promised to tear up the Erdogan-Serraj MOU on the EEZ demarcation. While urging a ceasefire in Libya, the Greek prime Minister, Mitsotakis, made it clear that Greece “will never accept a political solution for Libya that does not require the cancellation” of the MOU.

The Berlin Summit was thus convened against the background of this highly complex military and diplomatic situation, with many key international players drawn in (except the Trump Administration, which has so far avoided a firm stand, beyond one conversation in which Trump warned Erdogan not to make things worse in Libya). Hosted by Germany, but largely driven by the Russian and Turkish initiative – coordinated during Putin’s visit – it did lead to a (fragile) agreement once again on a ceasefire.

Haftar’s advance on the ground would thus be halted (although he is now using his control of the oilfields to exert further pressure on the GNA). But his very presence at the summit signaled a reluctant recognition of his role by Serraj and Erdogan, who in the past refused to accept the legitimacy of this “rebel” force. It has yet to be seen whether this would lead to broader negotiation on a political compromise between the two sides (and other forces controlling parts of Libya) or to another violent crisis.

Israel’s interests, at this tense time vis-à-vis Iran – and for many other good reasons – require an effort to avoid a violent confrontation in the eastern Mediterranean. Turkey may be hostile (the Directorate of Military Intelligence annual report named it, for the first time, as a threat), but it is not yet an active enemy. Everything short of a military confrontation needs to be done, though, to deter Erdogan from establishing a barrier diagonally across the Mediterranean, barring Cyprus, Egypt and Israel from connecting their gas infrastructure to Greece and hence to Europe.

While keeping a necessary low profile on Libyan internal affairs, Israel’s role should be focused upon working hand in hand with all EMGF partners, and in particular Greece and Cyprus. The latter have some influence on all three fronts – lobbying in the US; using their EU status and utilizing the links of common heritage that connect them to Russia.

All relevant players must now engage with the US, Europe and Russia seeking the annulment of the MOU. This would also serve as a signal to Erdogan to curb his ambitions.

In Washington – where the Hellenic nations as well as Israel have firm friends – both the Administration and Congress (which has already taken significant steps, such as the removal of the arms embargo on Cyprus) should be urged to take a firm stand against the Turkish EEZ map, which among other things threatens the stability of Egypt).

In Brussels and EU member states capitals, use can be made of the very quick, sharp and firm response made officially by the EU in response to the first leaks about the MoU – which decried it as being in contradiction with any possible interpretation of the Law of the Sea.

With Putin, the key will be to impress upon him that Egypt, Greece, Cyprus and Israel all expect Russia to strengthen Haftar’s hand. Russia seeks to enlarge its influence in Egypt. Greece and Cyprus have traditional links to Russia and to the Russian Church; and Cyprus is also a favored destination for Russian citizens. Israel has a unique dialogue with Russia, exemplified by Putin’s participation in the Holocaust commemoration in Jerusalem. All the countries expect Russia to strengthen Haftar’s hand, whether in the battle for Tripoli or at the negotiating table, to secure the cancellation of the MOU. Even if (and this is far from certain) Russia does prefer to see the EastMed pipeline blocked, this interest is far outweighed by their investment in Egypt and in Haftar’s parts of Libya.

JISS Policy Papers are published through the generosity of the Greg Rosshandler Family.

photo: U.S. Department of State from United States [Public domain]

- בניית אתרים

- בניית אתרים